Kibyra Ancient City: A Historical and Archaeological Site in Türkiye

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.kulturportali.gov.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Kibyra Ancient City is situated on a volcanic plateau near the modern village of Horzum, within the Gölhisar district of Burdur Province, Türkiye. The site occupies a naturally defensible position, perched between steep ravines and commanding extensive views over the fertile Gölhisar plain. Geographically, Kibyra lies at the confluence of three ancient regions—Pisidia, Pamphylia, and Lycia—making it a significant crossroads in southwestern Anatolia.

Archaeological evidence confirms that the site was occupied from the Hellenistic period onward, with substantial urban development occurring under Roman rule. Stratified deposits and epigraphic materials attest to continuous habitation through late antiquity and into the Byzantine era, although occupation diminished after the early medieval centuries. The extensive ruins spread across the plateau reflect the city’s historical prominence and its integration into regional political and economic networks.

Systematic archaeological surveys and excavations, primarily conducted by Turkish teams since the twentieth century, have documented numerous inscriptions, architectural remains, and material culture. These efforts have been complemented by scholarly publications and museum catalogues, with many artifacts housed in the Burdur Archaeological Museum. The site is protected under national heritage legislation and remains accessible for ongoing research and study.

History

Kibyra’s historical trajectory is closely linked to its strategic location at the intersection of Pisidia, Pamphylia, and Lycia. From its origins as a modest Iron Age settlement, it evolved into a powerful city-state during the Hellenistic period and later became a prominent Roman administrative center. The city’s development reflects broader regional dynamics, including shifting political allegiances, imperial integration, and religious transformations. Despite periods of prosperity, Kibyra experienced decline following late antique seismic events and changing geopolitical conditions, culminating in its abandonment by the early medieval period.

Iron Age Settlement (circa 4th–3rd century BCE)

Archaeological investigations have identified an early Iron Age settlement at Uytuptnar, approximately 18 kilometers from the later urban center of Kibyra. Material remains date this community to the 4th or 3rd century BCE. Ancient geographer Strabo records that the inhabitants of Kibyra traced their ancestry to Lydian migrants who settled in the region and intermarried with indigenous Pisidian populations. This cultural amalgamation eventually led to the relocation and expansion of the settlement, establishing the foundation for the later city. The early community likely maintained a tribal social structure with subsistence based on agriculture and pastoralism, consistent with regional Iron Age patterns.

Hellenistic Period (2nd century BCE)

Following the Treaty of Apamea in 188 BCE, which concluded hostilities between Rome and the Seleucid Empire, Kibyra was incorporated into the Kingdom of Pergamon under King Eumenes II. During this period, the city expanded its territorial influence, controlling areas extending from Pisidia and Milyas to Lycia and the Rhodian Peraea. Kibyra formed a political confederation known as the Tetrapolis with three neighboring Lycian cities—Bubon, Balbura, and Oinoanda. Within this alliance, Kibyra held two votes, reflecting its superior military capacity, which included an infantry force of approximately 30,000 and 2,000 cavalry, while the other cities each held one vote.

Governed by local tyrants, with Moagetes I documented as ruler during the Galatian War in 189 BCE, Kibyra developed a robust economy based on blacksmithing, leather processing, horse breeding, and pottery production. The city’s military strength and economic resources underpinned its regional dominance. This period marked Kibyra’s emergence as a significant political and military power in southwestern Anatolia.

Roman Conquest and Administration (133 BCE – 1st century CE)

In 133 BCE, the last Attalid king, Attalus III, bequeathed his kingdom to Rome, establishing the province of Asia. The precise administrative status of Kibyra following this transition remains unclear; it may have enjoyed a degree of autonomy similar to Lycia or been incorporated directly into the provincial system. During the First Mithridatic War in 83 BCE, Roman general Lucius Licinius Murena deposed the last local tyrant, Moagetes II, son of Pancrates, and dissolved the Tetrapolis confederation. Subsequently, Bubon and Balbura were assigned to the Lycian League, while Kibyra was integrated into Roman provincial administration.

Under Roman rule, Kibyra became the center of a large judicial district (conventus) encompassing 25 cities, including Laodicea on the Lycus, as recorded by Pliny the Elder. The city suffered a major earthquake in 23 CE during the reign of Tiberius but was rebuilt with imperial assistance from Emperor Claudius, who was honored by the addition of “Caesarea” to the city’s name. From 25 CE onward, Kibyra inaugurated public games under Roman patronage, signaling its renewed civic vitality. The poet Horace referenced Kibyra as a notable commercial center, possibly involved in grain export despite its inland location. Strabo noted the coexistence of four languages—Pisidian, Solymian, Greek, and Lydian—the latter extinct elsewhere, making Kibyra the last attested site of the Lydian language.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–4th century CE)

During the imperial era, Kibyra experienced significant urban and cultural development. Emperor Hadrian’s visit in 129 CE brought privileges that enhanced the city’s status. The reconstruction following the 23 CE earthquake included monumental public buildings such as the Odeon, initially constructed as a bouleuterion (council house) in the second half of the 2nd century CE and later adapted with a stage for theatrical performances and judicial proceedings. The Odeon is distinguished by its large Medusa mosaic floor and marble façade adorned with colored marble columns.

The stadium, measuring approximately 198 meters in length and 24 meters in width, hosted athletic competitions and gladiatorial combats, as evidenced by extensive gladiator friezes. Architectural remains reveal the use of local limestone in public buildings, including temples exhibiting Doric and Corinthian orders near the theater platform. A corpus of 448 inscriptions in Greek and Latin, dating from the 2nd century BCE through Late Antiquity, has been catalogued, providing detailed insight into the city’s political, social, and religious life. Artistic discoveries include 2nd-century CE statues and busts of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis and the god Asclepius, underscoring the city’s religious plurality.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–8th century CE)

In late antiquity, Kibyra became an early Christian bishopric, reflecting the spread of Christianity in the region. A catastrophic earthquake in 417 CE caused extensive damage, from which the city never fully recovered. Nevertheless, archaeological evidence indicates continued urban activity through the 5th and 6th centuries CE, including the construction of a late antique bath complex near the Odeon. The city’s inhabited area contracted around the Agora, which was fortified, while residential quarters and funerary zones persisted nearby.

Excavations in 2021 uncovered a basilica containing 30 tombs, believed to belong to prominent members of the local clergy, illustrating the Christian community’s presence and funerary customs. After the 6th century, occupation declined markedly, with only sporadic habitation into the late 9th century CE. The contraction of the urban fabric and the shift toward ecclesiastical leadership reflect broader regional transformations during this period.

Abandonment and Later History (8th century CE)

By the 8th century CE, the remaining inhabitants of Kibyra abandoned the site, relocating to the nearby settlement of Horzum, now modern Gölhisar. This abandonment corresponds with wider political fragmentation, economic decline, and changing settlement patterns in Anatolia during the early medieval period. Following this, Kibyra remained largely uninhabited, preserving its ruins until renewed archaeological interest emerged in the 21st century.

Modern Rediscovery and Excavation (2006–present)

Systematic archaeological excavations at Kibyra commenced in 2006 under the direction of the Department of Archaeology at Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Burdur. These investigations have revealed major public monuments, including the well-preserved Odeon with its distinctive Medusa mosaic, the stadium adorned with gladiator reliefs, several temples, and a late antique bath complex. The site encompasses approximately 405 hectares across three prominent hills composed of conglomerate rock, with construction primarily utilizing local limestone and conglomerate blocks.

Artifacts and inscriptions recovered from the site are exhibited at the Burdur Archaeological Museum. Since 2016, Kibyra has been included on Turkey’s tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage status, recognized for its exceptional urban planning, monumental architecture, and artistic achievements. Ongoing research continues to refine understanding of the city’s historical development and cultural significance.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Iron Age Settlement (circa 4th–3rd century BCE)

The earliest community associated with Kibyra, located at Uytuptnar, was characterized by a culturally mixed population of Lydian migrants and indigenous Pisidian groups. Social organization likely revolved around kinship and tribal structures, with local leaders overseeing agricultural and pastoral activities. Subsistence strategies included cultivation of cereals, pulses, and olives, alongside livestock husbandry. Domestic architecture consisted of simple stone and mudbrick constructions, with interior spaces arranged for practical use, including hearths and storage. Trade was probably limited to local exchange networks, facilitated by footpaths and pack animals. Religious practices likely involved indigenous Anatolian cults, though specific deities remain unidentified due to lack of direct evidence.

Hellenistic Period (2nd century BCE)

Under Pergamene rule, Kibyra expanded both territorially and demographically, incorporating diverse ethnic groups including Pisidians, Lycians, and Lydians. The city’s social hierarchy featured an aristocratic elite and a professional military, with documented forces of 30,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Economic life diversified, with specialized crafts such as blacksmithing, leatherworking, and pottery production operating at household and workshop levels. Agriculture remained central, supporting horse breeding and grain cultivation. Archaeological parallels suggest domestic interiors began to include decorative elements like painted plaster and mosaic floors, reflecting Hellenistic artistic influences. Markets facilitated trade in local and imported goods, transported via regional routes connecting Pisidia, Lycia, and Pamphylia. Religious life centered on traditional Anatolian and Greek deities, with temples serving as venues for civic and military ceremonies. Kibyra’s leadership of the Tetrapolis underscored its political and military prominence.

Roman Conquest and Administration (133 BCE – 1st century CE)

Following Roman annexation and the dissolution of the Tetrapolis, Kibyra developed into a municipium with judicial authority over a large district of 25 cities. The population included Roman settlers, local elites, and freedmen, as evidenced by inscriptions naming magistrates and duumviri. Social stratification became more formalized, with civic offices and imperial patronage shaping governance. Economic activities expanded, including coin minting and large-scale grain production supporting local consumption and export. Archaeological finds of amphorae and trade goods corroborate Horace’s reference to Kibyra as a commercial center. Residential architecture improved, featuring mosaic floors and painted walls. Diet incorporated bread, olives, fish, and imported delicacies. Workshops and markets thrived, producing textiles, metalwork, and pottery. Transportation relied on maintained roads facilitating movement of goods and officials. Religious practices blended traditional Anatolian cults with Roman imperial worship. The coexistence of four languages—Pisidian, Solymian, Greek, and Lydian—reflects a multicultural society. Civic structures included a bouleuterion and public games, reinforcing Kibyra’s regional administrative and cultural role.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–4th century CE)

Kibyra reached its zenith during the imperial era, particularly following Emperor Hadrian’s visit in 129 CE. The population was cosmopolitan, comprising Roman citizens, local aristocracy, artisans, and clergy. Inscriptions document civic officials and religious leaders, indicating a complex social hierarchy. The economy was multifaceted, encompassing agriculture, artisanal production, and entertainment industries such as gladiatorial games supported by the stadium and Odeon. Residential buildings featured sophisticated interior decoration, including the unique Medusa mosaic in the Odeon and marble façades, reflecting wealth and Roman cultural integration. Diet remained diverse, with archaeological remains showing consumption of cereals, olives, fruits, and fish. Markets offered local produce and imported luxury goods transported via regional roads. Religious life was diverse, with temples dedicated to Serapis, Asclepius, and traditional Greco-Roman deities. Public festivals, games, and theatrical performances fostered civic identity. Kibyra functioned as a prominent municipium with judicial authority and imperial privileges, evidenced by monumental architecture and extensive epigraphic records.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–8th century CE)

Following the 23 CE earthquake and subsequent rebuilding, Kibyra’s urban area contracted but remained active into late antiquity. The population gradually Christianized, establishing an early bishopric and constructing a basilica containing clergy graves. Social organization shifted toward ecclesiastical leadership alongside traditional civic offices. Economic activity became more localized, focusing on sustaining the reduced urban population. Archaeological evidence of a late antique bath complex and fortified Agora indicates continued public life, though on a smaller scale. Domestic architecture included rubble-built houses with modest decoration. Diet likely remained consistent with earlier periods but adapted to changing economic conditions. Religious practices centered on Christianity, with basilicas replacing pagan temples and Christian funerary customs becoming prominent. The city’s administrative role diminished but retained ecclesiastical significance. Defensive walls and settlement contraction reflect responses to regional instability and natural disasters.

Abandonment and Later History (8th century CE)

By the 8th century, Kibyra’s remaining inhabitants relocated to nearby Horzum, leading to the city’s abandonment. Urban infrastructure fell into ruin, and the site ceased to function as a civic or religious center. This transition reflects broader regional transformations, including political fragmentation and economic decline. No evidence indicates continued occupation or economic activity after this period.

Remains

Architectural Features

Kibyra’s archaeological remains cover approximately 405 hectares across three prominent hills composed of conglomerate rock. The urban layout reveals a planned arrangement of public, civic, and religious buildings concentrated on these hills. Construction predominantly employed locally sourced limestone and conglomerate blocks. No city walls or fortifications have been identified or preserved, leaving the city’s ancient boundaries archaeologically undefined. During late antiquity, the inhabited area contracted around the Agora, which was fortified, while residential and funerary zones extended nearby. Excavations have uncovered ceramic workshops dating to the 5th–6th centuries CE near the Odeon’s front area, constructed with small rubble stones and reused architectural blocks (spolia). The extant architectural remains span from the Hellenistic period through Late Antiquity, with visible structures mainly from the Roman imperial and Byzantine eras.

Key Buildings and Structures

Odeon

The Odeon, situated in the densely occupied southwest corner of the hill, was constructed in the second half of the 2nd century CE as the city council assembly (bouleuterion). During the Imperial Roman period, it was modified by adding a stage (skena) to function as a theater and courtroom for significant trials in Asia Minor. The façade was clad in marble and adorned with colored marble columns. The orchestra measured approximately 9.8 by 5.8 meters and was paved with finely cut marble slabs in white, red, purple, and gray, arranged in an opus sectile technique. A central Medusa head mosaic, notable for its size and craftsmanship, decorates the orchestra floor. The proscenium facing the audience was made of thin colored marble plates featuring decorative motifs on doors and columns. In front of the Odeon stands a stoa with nine columns and a mosaic floor dated by inscription to 249–254 CE, sponsored by Aurelius Sopatros and the Klaudius Theodoros brothers. The Odeon’s seating area offers views over the Cibyratic plain and surrounding mountains.

Stadium

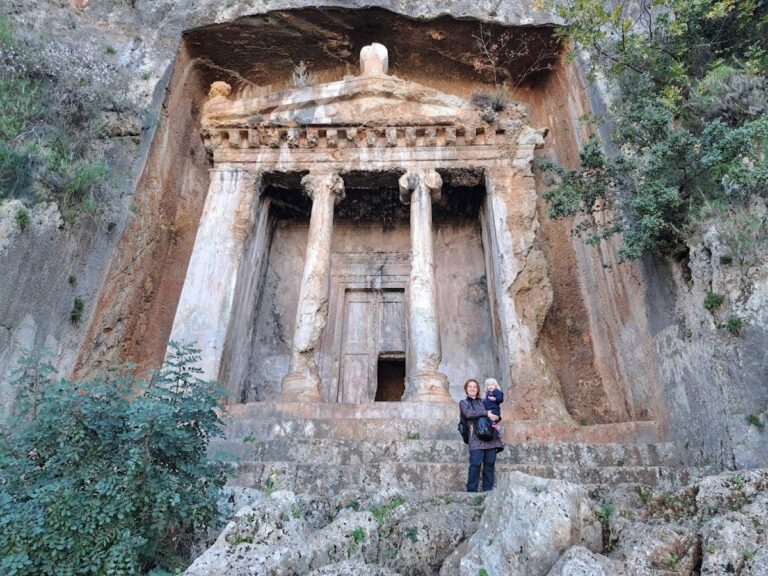

The stadium is located at the lower extremity of the ridge on which Kibyra stands. It measures approximately 198 meters in length and 24 meters in width. The structure was used for athletic races and gladiatorial combats, as evidenced by extensive gladiator friezes found on site. The hillside was partially excavated to accommodate the stadium’s form. On the hill side, 21 rows of seats follow the curve of the stadium, culminating in a theater-like termination at the upper end; this section is well preserved though some seats are displaced by vegetation. Opposite these, seating consists of marble blocks placed on a low wall along the terrace edge formed by cutting into the hill. The seating overlooks the Cibyratic plain. Near the stadium entrance, an eastward ridge features a paved way bordered by sarcophagi and funerary monuments, beginning with a massive Doric-style triumphal arch now in ruins.

Temples

Several large temple ruins are located near the theater platform. These include examples of Doric and Corinthian architectural orders. The temples remain in a ruined state and are primarily identified through architectural fragments and surface traces. No complete temple structures survive, but the scattered remains indicate multiple religious buildings once stood in this area. Inscriptions or dedicatory evidence specifying the deities worshipped have not been conclusively identified.

Basilica with Tombs

Excavations in 2021 uncovered a Late Antique basilica containing 30 tombs. Most tombs are believed to belong to prominent members of the city’s Christian clergy, reflecting the ecclesiastical presence during the 4th to 8th centuries CE. The basilica’s architectural remains include burial chambers integrated within the church structure, providing insight into early Christian funerary practices at Kibyra.

Late Antique Bath Complex (Hamam)

The bath complex is situated between the Odeon’s stoa and the nearby temple ruins at the southeast corner of the site. It is well preserved and partially restored for research access. The bath comprises five sequential rooms aligned north to south, with a total length of 23.3 meters and a maximum width of 7.57 meters. The rooms include an apodyterium (changing room), frigidarium (cold room), tepidarium (warm room), and two caldaria (hot rooms), one of which served as a sweating chamber. The entrance is located on the west wall of the apodyterium. A later addition along the eastern wall consists of a rectangular annex with two small rooms, likely used for storage. The bath’s drainage system runs through a narrow corridor between the bath and an adjacent temple stylobate. Construction employed small rubble stones and reused blocks, dating the complex to the 5th–6th centuries CE.

Other Remains

Surface surveys and excavations have revealed workshops related to ceramic production active in the 5th–6th centuries CE near the Odeon’s front area. These workshops were constructed with small rubble stones and spolia blocks. An avenue near the stadium entrance is lined with sarcophagi and funerary monuments, indicating a necropolis area adjacent to the city. No city walls or military fortifications have been identified. The overall urban plan shows a coherent arrangement of public, civic, and religious buildings on the three hills.

Archaeological Discoveries

A corpus of 448 inscriptions in Greek and Latin has been documented at Kibyra, dating from the 2nd century BCE through Late Antiquity. These inscriptions include political, social, and religious texts, notably a bilingual Greek-Latin treaty from 174 BCE. The inscriptions provide direct evidence of the city’s administrative and civic life.

Statues discovered at the site include busts of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis and statues of Asclepius, found in 2019 and 2020. These sculptures date to the 2nd century CE and reflect the religious diversity of the city. The artistic style corresponds to Roman imperial craftsmanship.

Additional finds include gladiator friezes associated with the stadium, mosaics such as the Medusa head in the Odeon’s orchestra, and various architectural fragments from temples and public buildings. Ceramic workshops uncovered near the Odeon indicate local pottery production during the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

Preservation and Current Status

The Odeon is well preserved, with its marble façade, mosaic floor, and structural elements largely intact. The stadium’s hillside seating remains visible, though some seats are displaced by vegetation. The Doric-style triumphal arch near the stadium entrance survives only as ruins. Temple remains are fragmentary, identified mainly through scattered architectural elements.

The Late Antique bath complex is well preserved and has undergone partial restoration to allow access for research. The basilica with tombs retains its burial chambers and structural outline. Ceramic workshops and other minor structures survive as surface remains or partial foundations.

Systematic excavations have been ongoing since 2006 under Mehmet Akif Ersoy University. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing and restoring key monuments, including the Odeon and bath complex. The site is protected under national heritage laws and has been proposed for UNESCO World Heritage status since 2016. No specific environmental or human threats are detailed in the sources.

Unexcavated Areas

The majority of Kibyra’s 405-hectare area remains unexcavated. While surface surveys have identified architectural fragments and potential buried remains, large portions of the city, including residential quarters and peripheral zones, await systematic archaeological investigation. No detailed plans for future excavations or limitations due to modern development are mentioned in the sources.