Château de Alpuente: A Historic Fortress in Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Very Low

Country: Spain

Civilization: Unclassified

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

The Château de Alpuente is located in the town of Alpuente in Spain and was originally constructed by Muslim rulers. Its origins date back to the 10th century during the caliphal era, when it was established as a fortress perched on a rocky hill to secure the surrounding territory. This castle maintained a subordinate relationship with another nearby fortress, Castillo del Poyo or Collado, situated about ten kilometers to the north, highlighting its role within a defensive network.

Following the Christian Reconquista, the castle continued to serve as a strategic military site due to its proximity to the shifting border between the kingdoms of Aragón and Castilla. Throughout the 14th century, during the Wars of the Union, the fortress underwent significant renovations to strengthen its defenses. In this period, the town of Alpuente gained prominence as a toll point along an important livestock route, especially for sheep, illustrating the castle’s ongoing importance not only militarily but economically. Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the castle was repeatedly contested in conflicts between Aragón and Castilla, reflecting its critical border position.

In the early 18th century, after the War of Spanish Succession, the castle was deliberately demolished by order of King Felipe V, who represented the new Bourbon dynasty. This action was taken as punishment because the fortress had supported the Habsburg claimant to the throne. Despite this destruction, the castle was rebuilt in the 19th century during the Carlist Wars, a time of internal civil conflicts. Notably, in 1835 during the First Carlist War, it was occupied by Carlist forces under the leadership of Cabrera. The defenders enhanced the castle’s defenses by constructing four artillery batteries within the citadel. These fortifications enabled them to resist a siege by liberal forces commanded by General Azpiroz. The fortress was also used later during the Third Carlist War.

Following the First Carlist War, authorities once again ordered the castle’s demolition to prevent its future military use by Carlist supporters. Over subsequent decades, damage from warfare, neglect, and the removal of stones for local construction contributed to the castle’s current ruined state. Archaeological investigations have uncovered remains of medieval residential buildings dating from the 11th to 13th centuries, demonstrating continuous occupation and adaptations across different historical periods.

Remains

The Château de Alpuente occupies a narrow, rocky ridge approximately 250 meters in length and 16 meters wide, towering over the town below. The fortress is strategically set above steep cliffs, especially on the eastern side where a vertical drop of about 150 meters falls into the Reguero ravine. Access to the castle was restricted to a single narrow mountain path carved directly into the rock, passing through a series of three gates, which no longer survive. This difficult approach provided strong natural protection.

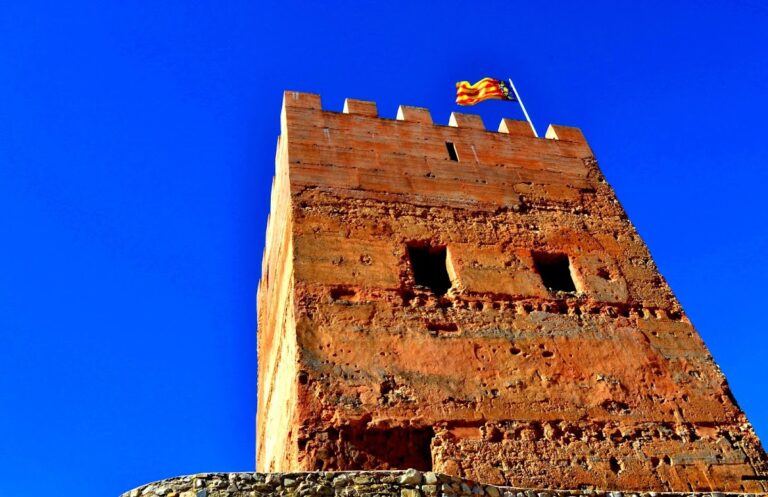

Surviving elements include fragments of defensive perimeter walls built on strong foundations and the bases of several towers. Some towers, notably the Torre de la Veleta—also known as Torre del Penell or Torre del Homenaje—remain partially standing. This large tower is constructed with carefully cut stone blocks fitted in ashlar masonry and still rises about 10 meters high. It marks the most intact above-ground structure despite repeated demolitions over the centuries.

Beneath the castle lie vaulted underground chambers, some resembling dungeons, and cisterns known as aljibes for collecting and storing water. These cisterns have ventilation shafts and access wells, and their interior surfaces are coated with a distinctive red plaster called almagra. When these water reservoirs were no longer in use, they were repurposed by adding new masonry walls and doors, demonstrating the castle’s adaptation to changing needs. The southern sector of the fortress, nearest to the parish church, shows the best preservation of surface structures and subterranean rooms and passages.

Excavations have revealed medieval living quarters with lime mortar floors and walls built from a mixture of masonry styles, including caliphal stonework, finished with fine lime plaster. Above these medieval foundations, 19th-century Carlist artillery batteries were constructed. These batteries consist of broad parapets with vertical retaining walls on the inside and sloping earth or masonry protections on the outer faces. To date, two of the four batteries identified during the Carlist Wars have been excavated.

The original castle entrance was marked by a ramp over three meters wide, featuring a carefully prepared stone pavement that could accommodate cavalry and small carts. Historical comparisons suggest the ramp may have been enclosed by a high parapet, creating a covered passage similar to those found in nearby medieval fortresses such as the castle of Chulilla.

At the base of the rock formation lie six semi-spherical basins hewn directly into the stone, with surfaces treated by bush-hammering to create texture. These basins are believed to have been used for grinding gunpowder or manufacturing ammunition, highlighting the practical military functions of the site.

Surrounding the medieval village on the western side were town walls extending about 600 meters in length, featuring fourteen towers each measuring between six and eight meters thick. Most of these towers are heavily eroded, and some were demolished in the late 20th century to accommodate street widening. Among these fortifications, the Torre Aljama stands out as the best preserved. This tower is a rectangular structure rising 16 meters high, built from ashlar masonry, topped with battlements, and includes a semicircular arch. Historically, this tower functioned as the main gate to the town and housed important municipal functions. The upper floor served as the town hall and a space for trading activities, with an additional council chamber added during the 16th century.