Castillo del Águila: A Historic Fortress in Gaucín, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: castillodelaguila.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

The Castillo del Águila, located in the town of Gaucín in Spain, was originally built by the Romans. Over the centuries, the castle saw multiple periods of construction, destruction, and rebuilding, reflecting the changing powers in the region. It was notably reconstructed during the Andalusian era, incorporating Islamic military architecture and serving as a vital stronghold in the surrounding area.

In the early 10th century, the castle played a role in the conflicts of the time. Historical accounts record an event in 914 when locals observed from the fortress the destruction by fire of Omar ben Hafsún’s fleet in the nearby port of Algeciras. By the 11th century, the castle—known then as Gauyan—came under the control of Abd al Yabbar, son of the muluk al-Tawil ruler Al-Mutamid, indicating its strategic importance during Muslim rule in Al-Andalus.

The castle’s history is closely linked to the struggle between Christian and Muslim forces. In 1309, the fortress became the scene of the death of Guzmán el Bueno, a legendary Spanish nobleman and military leader, as Christian troops attempted to capture it from the Arabs. Eventually, in 1485, Christian forces succeeded in taking control of the castle. Pedro Castillo became its first Christian governor, or alcaide, followed by a succession of others including Juan de Torres in 1496, Juan Maraver in 1513, and Juan de Campo Vaca de Mendoza in 1559, highlighting the fortress’s continued military and administrative significance after the Reconquista.

Centuries later, during the French invasion of Spain in 1810, the castle served as a center of resistance. Despite being defended by a small group led by Antonio de Molina y Navarro, the fortress was taken after a determined defense. In 1839, General José Serrano Valdenebro initiated significant repairs to restore the castle after considerable damage. These works included repairing a large breach in the walls, cleaning water cisterns, and restoring the oven, making the fortress capable of housing a garrison of up to 80 soldiers and officers. By 1842, it held 40 troops along with artillery pieces such as cannons and howitzers. However, in 1843, an explosion in the powder magazine caused severe new damage.

The castle has also been the subject of archaeological studies, which uncovered artifacts such as 10th-century caliphal oil lamps and decorated ceramics from the Almohad period. Its historic and cultural value has been formally recognized and protected under Spanish heritage laws since 1949 and especially from 1985 onward, with further special status granted by the regional authorities of Andalusia in 1993.

Remains

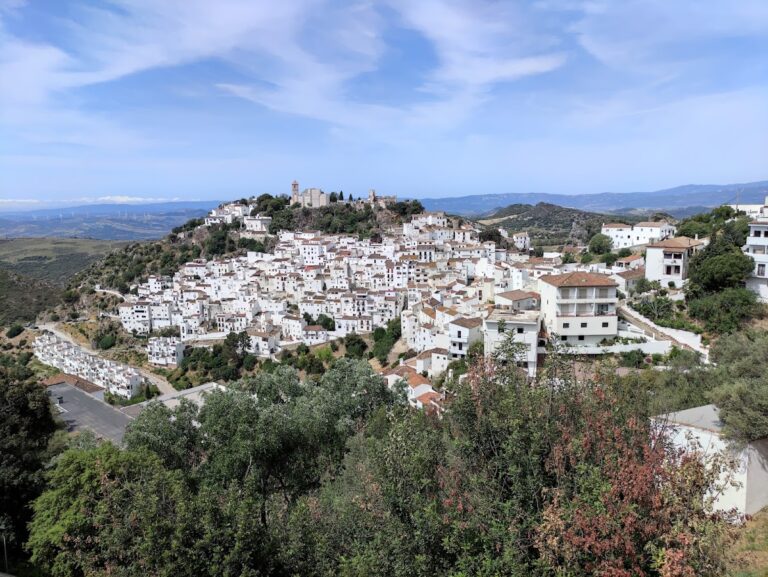

The Castillo del Águila is perched atop a hill rising 688 meters above sea level and features an irregular layout composed of three distinct walled enclosures. Its defensive walls are built primarily of limestone and brick, reflecting a blend of construction techniques from its various phases of occupation.

The outermost enclosure serves as the first defensive ring and includes two primary gates. The main entrance, situated on the eastern side facing the Genal valley, is formed by a pair of arches: a large pointed arch made of brick, supported on limestone rocks and fitted with arrow slits for archers, capped by a wall of ashlar masonry with a battlement walk. Behind this arch is a deeper semicircular vaulted arch also constructed in brick and set within a framed alfiz—a rectangular decorative border typical of Islamic architecture. A similar gate with defensive arrow openings exists to the north, following the same construction style. This enclosed space provided protection for people and livestock, enclosed by a tall limestone wall pierced with arrow slits.

Within the first enclosure are the remains of several auxiliary buildings, including the Hermitage of the Santo Niño and a historic hospital, both located on the eastern side. On the opposite side stands the Torre de la Regente, a square tower near the powder magazine that suffered an explosion in the mid-19th century. Nearby rocky outcrops preserve traces of military structures and evidence of earlier settlements, including fragments of Iberian pottery and the oldest cistern carved directly into the rock, known as the albacar, which suggests early water storage facilities.

The middle enclosure is constructed with a combination of masonry and brick and houses two large cisterns positioned at opposite ends, underscoring the importance of water collection and storage for the fortress’s occupants.

The innermost enclosure, or citadel, is square in plan and accessed through a double brick archway in reddish brick, a feature dating to the Muslim period. It consists of two distinct masonry levels that alternate brick and limestone materials. The lower level, identified as originating from the 10th-century caliphal period, was confirmed through finds such as caliphal oil lamps placed in cavities within the walls. Above this lies the Torre de la Reina, a later addition serving as a bell tower, representing architectural evolution in the site’s history.

Additional elements within the castle complex include surviving walls, a keep tower, multiple cisterns for water storage, and an escape tunnel mined into the rock, providing a secret exit in times of siege. Decorative brick arches framed by alfiz and strategic arrow slits remain visible and exemplify the blend of defensive and aesthetic considerations in the castle’s design. Archaeological excavations have also recovered caliphal oil lamps with small drip spouts and Almohad ceramics decorated in the cuerda seca technique, characterized by brightly colored, clearly separated glazes, some fitting basin shapes, revealing the richness of the material culture associated with the fortress.