Caernarfon Castle: A Historic Welsh Fortress in North-West Wales

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: cadw.gov.wales

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

Caernarfon Castle is located in the town of Caernarfon in north-west Wales. It occupies a site first developed by the Romans for military purposes, before later fortifications were established by Norman and English rulers.

The earliest known fortification near the site was the Roman fort Segontium, constructed around AD 75. This stronghold was strategically placed to control the surrounding area and remained in use until about AD 394, when it was abandoned during the decline of Roman Britain. The proximity and name of Caernarfon are related to this Roman presence, reflecting a continuity of defensive importance in the location.

Following the Norman conquest of England, a timber motte-and-bailey castle was erected around 1093 on a peninsula bordered by the River Seiont and the Menai Strait. This early castle featured wooden palisades and earthworks and served as a foothold to establish control over the region. Over time, this initial structure was incorporated into later developments.

In 1283, after subduing Wales, King Edward I of England commissioned the construction of the current stone castle on the site of the former Norman fortification. This project was part of Edward’s larger campaign to consolidate English rule over Wales through a series of fortified castles known collectively as the “iron ring.” Caernarfon became the administrative hub for north Wales under English governance and a symbol of the new order.

Throughout its history, the castle faced several military challenges. It was captured and damaged during the Welsh rebellion led by Madog ap Llywelyn between 1294 and 1295. Later, during the Welsh uprising known as the Glyndŵr Rising from 1400 to 1415, Caernarfon endured a siege reflecting ongoing Welsh resistance to English rule. In the 17th century, during the English Civil War, the castle was held by Royalist forces and subjected to three sieges before surrendering in 1646.

After the Tudor dynasty ascended the English throne in 1485, tensions between Wales and England lessened significantly, reducing the castle’s military relevance. Over the following centuries, the fortress deteriorated, with wooden elements decaying and roofing lost by the early 1600s. It remained largely neglected until the late 1800s, when government-sponsored restoration began under the leadership of deputy-constable Llewellyn Turner. This restoration involved substantial rebuilding, drawing some criticism for its departure from pure conservation.

In modern times, Caernarfon Castle hosted significant investiture ceremonies for the Prince of Wales in 1911 and 1969, events that reinforced its role as a place of political symbolism in Welsh-English relations. Today it is protected as a heritage site, reflecting both its military history and cultural importance.

Remains

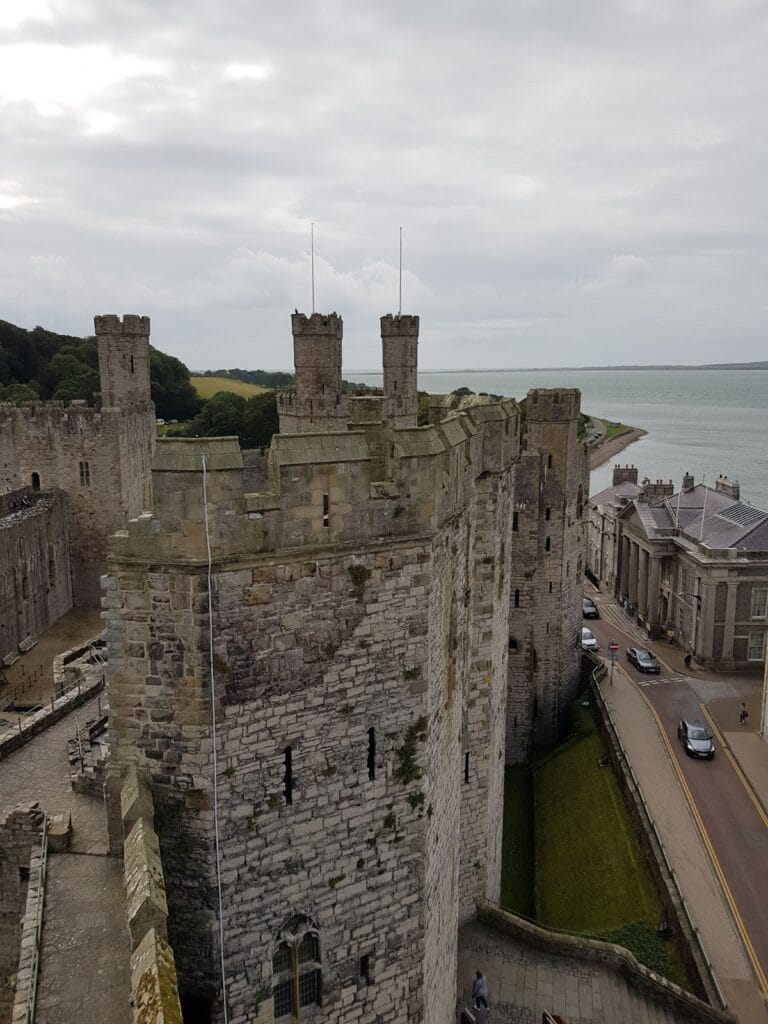

Caernarfon Castle is arranged in a roughly figure-eight shape oriented east to west. Its design integrates the earlier Norman motte, or earth mound, and is divided into two main sections: a smaller upper ward to the east and a larger lower ward to the west. The upper ward was intended to house royal lodgings, a plan that remained unfinished, while the lower ward contained domestic buildings such as kitchens and the Great Hall.

The castle’s outer defenses are formed by strong curtain walls lined with numerous polygonal towers. These towers, mostly four stories tall including basements on the northern side, were designed with angles that allowed defenders to fire along the walls, enhancing protection. Notably, the Eagle Tower located at the western corner is the largest tower and once displayed three turrets topped with eagle statues. Inside, it featured spacious lodgings thought to have belonged to Sir Otton de Grandson, an important English official in Wales. This tower also included a water gate connecting it directly to the River Seiont, allowing for boat access.

Water for the castle was drawn from a well within the Well Tower, a structure named for this purpose. The castle’s walls exhibit distinctive colored bands of stone, a decorative technique that, along with the polygonal shape of the towers, evokes the imagery of the ancient Walls of Constantinople. This design choice has been interpreted as expressing a connection to imperial authority and linking the castle symbolically to Roman and Arthurian traditions.

Two principal gatehouses control access to the fortress. The King’s Gate, facing the town, was planned as a formidable entrance featuring multiple drawbridges, portcullises (heavy grates lowered to block access), and murder holes designed for defensive attacks on invaders. Above this gate stands a niche housing a statue of King Edward II looking out over the settlement. The Queen’s Gate provides another approach to the castle; its entrance stands above ground level due to the raised interior terrain from the earlier motte, and it was originally reached by a stone ramp that no longer survives.

Within the castle walls, surviving foundations mark where key buildings once stood. The Great Hall’s base measures about 30.5 meters (100 feet) in length and served as a space for official gatherings and royal ceremonies. Adjacent to the King’s Gate are the kitchen foundations, though their relatively light construction suggests they were less robust than other castle structures. Defensive features include battlements along the southern walls and firing galleries designed to provide cover for archers and soldiers—only those on the southern side were completed, while those planned for the north were never built.

Constructing the castle demanded significant labor and resources. Hundreds of workers dug the extensive moat and ditch surrounding the fortress. Timber was transported from as far as Liverpool, while the stone used came from local quarries on Anglesey and nearby regions. Between 1283 and 1330, the castle’s building costs ranged from £20,000 to £25,000, at the time an extraordinary military investment exceeding the expenses for comparable fortresses such as Dover Castle and Château Gaillard.

Today, the castle’s walls and towers largely survive intact, but the interior buildings remain only as rubble foundations, revealing where grand halls and lodgings were planned but never completed. These ruins offer insight into the ambitions of King Edward I’s vision to establish a powerful seat of English rule in Wales.