Burgruine Fragenstein: A Medieval Castle Ruin in Zirl, Austria

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Austria

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Burgruine Fragenstein is a hilltop castle ruin situated in the municipality of Zirl, Austria. It was constructed by the Counts of Andechs, a noble family of the early medieval period, most likely in the early 12th century. The castle’s main purpose was to oversee and control the salt trade route crossing the nearby Seefelder Sattel mountain pass, enabling its owners to collect tolls and taxes.

By the early 13th century, Fragenstein had become the seat of the Herren von Fragenstein, a group of ministeriales serving the Andechs family. A record from 1232 names a figure called Hageno de Fragenstain, indicating their established role. Prior to 1248, ownership transferred to the Counts of Tyrol. During this time, the castle assumed an administrative function as a judicial seat, particularly noted for its association with legal interrogations and punishments, which may have influenced the castle’s name, linking to the German word “Frag” (meaning “question”) and the use of judicial torture, often described as “peinliche Frag.”

Throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, Fragenstein changed hands several times. In 1254, Gebhard von Hirschberg held it as a fief but sold it three decades later to Meinhard II of Tyrol. Meinhard II granted the property to Otto Charlinger, who managed the salt works. At some point, the judicial center associated with the castle moved to another location called Hörtenberg. In 1345, revenues collected from tolls in the nearby town of Zirl were officially allocated to maintain the castle’s upkeep.

Control of Fragenstein passed next to Ruprecht Kärlinger and then to Berthold von Ebenhausen until 1365. That year, Parzival I von Weineck became the owner and undertook the construction of the western bergfried, a prominent defensive tower. The Weineck family maintained ties with notable cultural figures; for example, the minstrel Oswald von Wolkenstein visited the castle in 1419 and 1426, connected to Parzival II von Weineck.

In the early 15th century, the castle was involved in regional political struggles. Parzival II participated in a rebellion by nobles against the ruling Tyrolean authority. In 1426, after being compelled to surrender, Parzival sold Fragenstein to Duke Friedrich IV, although the formal legal transfer did not occur until 1446. Thereafter, the castle was managed by appointed stewards representing the duke’s interests.

Under the reigns of Sigmund the Rich and Emperor Maximilian I in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Fragenstein saw expansions and was repurposed in part as a hunting lodge. A chapel was consecrated within the residential wing known as the palas in 1469, reflecting both the religious practices and lifestyle of the castle’s occupants.

During the 17th century, Fragenstein’s location was used strategically as a beacon station in 1647, serving as an important point of communication between other lookout stations at Flaurling and Vellenberg. However, changes to regional road networks diminished the castle’s military and economic relevance, leading to its gradual decline.

Starting from 1662, the castle was pledged to Johann Martin Gumpp, a court architect who focused on rebuilding the manor house situated below the ruins but allowed the castle itself to fall into disrepair. During the War of Spanish Succession in 1703, Tyrolean troops briefly took refuge at Fragenstein. To prevent capture by enemy forces, they intentionally destroyed the castle, while the manor below was burned and later rebuilt by Gumpp.

By the late 18th century, Fragenstein was already recognized as a ruin. Ownership remained with the Gumpp family until the early 19th century, after which the property was pledged and partially sold to local owners in 1843. The Kuen family has been the primary owner from that point onward. The castle was mentioned in the 1855 Baedeker travel guide, noted as a quadrangular tower ruin and as a former favorite residence of Emperor Maximilian I.

In 1877, a significant collapse affected the northeast quarter of the east tower and the palas. Initial measures to stabilize the ruins began in 1933 under the Austrian Castle Association, followed by a more comprehensive restoration program completed between 1974 and 1978. Today, Burgruine Fragenstein is protected as a historic monument.

Remains

Burgruine Fragenstein is built on a narrow rocky ridge, which features steep drops to the south overlooking the Inn valley, and nearly vertical cliffs on the east side descending to the Schlossbergklamm gorge. The castle’s defensive location takes advantage of natural rock formations, with fortifications developed to control access along the ridge.

Two major square towers form the most prominent surviving structures. The older bergfried dates from the 13th century and was originally covered with plaster. Measuring about 11 meters on each side, its interior space spans more than 50 square meters per floor, providing considerable room within the thick stone walls. The corners of the bergfried are emphasized with bossage stones—large blocks with protruding edges that were often used to reinforce important structural points.

Within the bergfried, the ground floor contains a dungeon, accessible only from the first floor via an internal opening, featuring a single small slit facing south that allowed limited light inside. The main entrance was on the first floor, likely reached by a drawbridge to a round-arched door situated centrally on the south side and cleverly hidden from approach by enemies. Another door on the east side was mostly lost due to the collapse of the tower’s northeast corner in the late 19th century but was reconstructed around 1960. A notable feature near the southeast corner is a fireplace deeply embedded within the thick wall, complete with decorative bossed edges; its chimney continues within the wall to an upper-level niche, suggesting a well-designed heating system. The bergfried’s north and west walls, which faced potential attackers, have no windows but include later Gothic additions such as shutter hinges on blind window openings.

Attached to the bergfried’s south side was the palas, the main residential building of the castle, whose steeply sloped roof outlines can still be traced on the remaining plaster.

Fragments of the western Romanesque ring wall survive, curving at a right angle along the valley side and enclosing the rocky ridge on three sides. This defensive wall protected a nearly vertical rock outcrop about 15 meters long and 5 meters wide. Another ring wall extends downhill from the bergfried toward the field side, possibly guarding the castle’s gate tower, though only minimal traces remain.

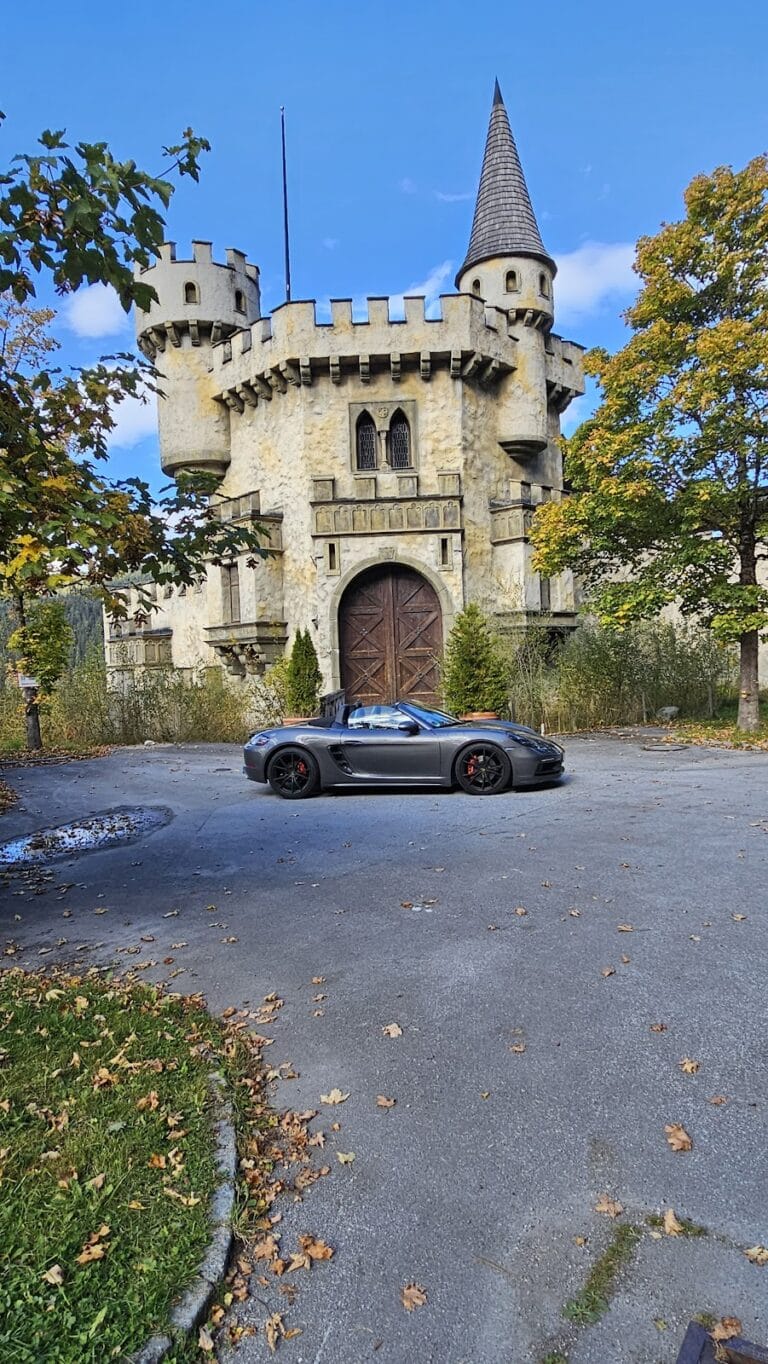

Approximately 100 meters northwest and situated above the main castle lies the Weinecker Tower, a later Gothic outwork associated with the Bozen family Weineck who acquired the castle in the late Middle Ages. It stands about 30 meters high and is composed of rubble stone walls between 1.6 and 2.0 meters thick. Each side of this tower measures roughly 7.75 meters. The original entrance was placed on the second floor on the east side to enhance security. At the top level, a large round-arched opening extends nearly the entire interior width but is offset to one side; the purpose of this substantial feature remains unclear. The tower acquired its steep pyramid-shaped roof during restoration work completed in the last quarter of the 20th century.

Together, these ruins illustrate the castle’s evolution over centuries, from a 12th-century fortification securing trade routes to a noble residence, judicial center, and hunting lodge, before its destruction and eventual preservation as a historical site.