Brough Castle: A Norman Fortress in Cumbria, England

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.english-heritage.org.uk

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

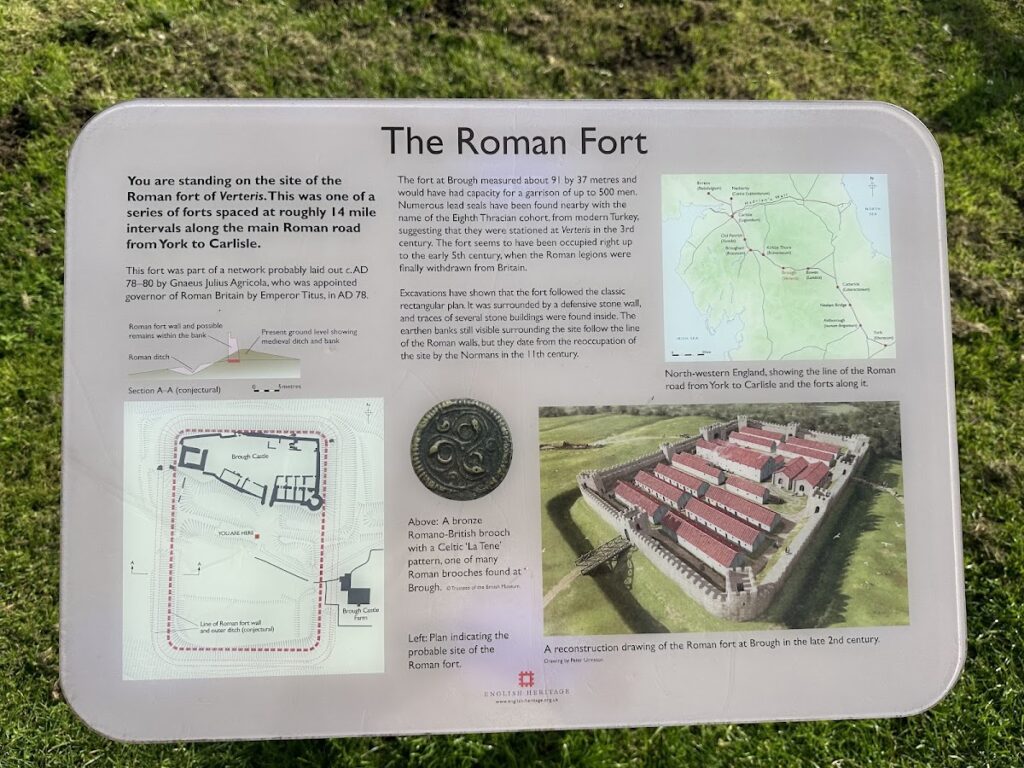

Brough Castle is located in Church Brough, in the modern county of Cumbria, England. It was built by the Normans shortly after their conquest of England in the late 11th century, reusing the site of a former Roman fort known as Verterae.

The castle’s earliest phase began around 1092 under King William Rufus, who established it within the remains of the Roman fort. This location was chosen for its strategic importance, guarding the Stainmore Pass and a vital Roman road linking Carlisle to Ermine Street, which was essential for controlling trade and military movements along the contested Anglo-Scottish border. Originally, the castle featured a motte-and-bailey design, combining stone foundations for the keep with timber upper structures and wooden defensive palisades.

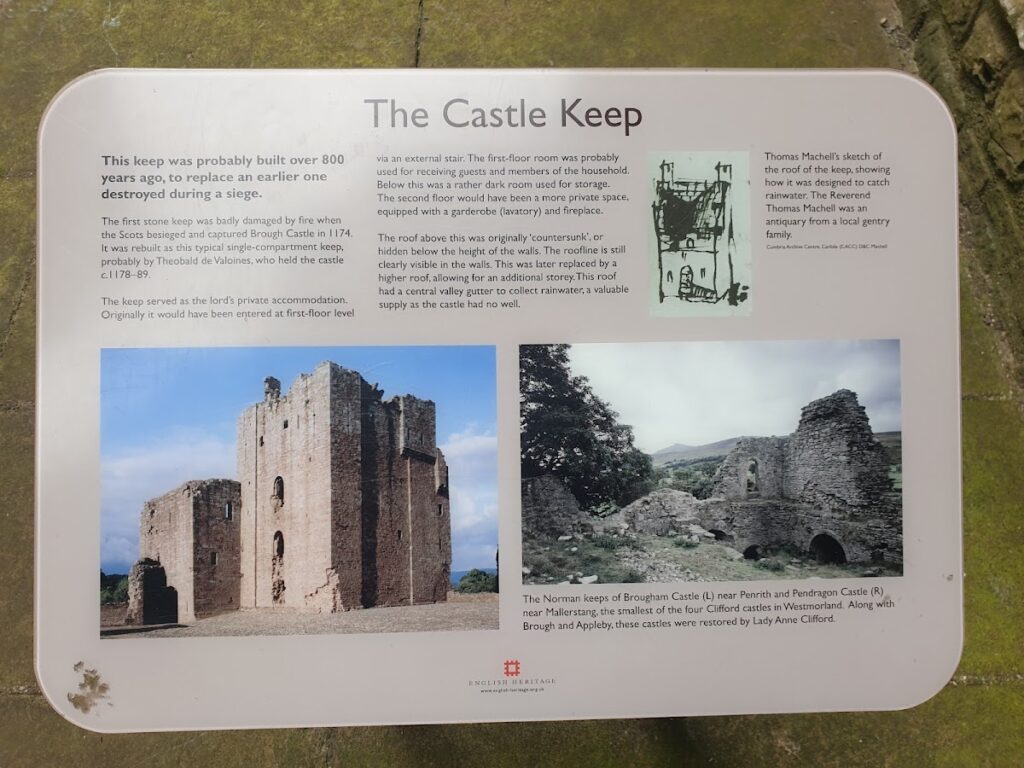

In 1174, during the Great Revolt against King Henry II, Scottish forces attacked and severely damaged the castle. In response, Henry II oversaw the construction of a square stone keep in the 1180s. This keep was integrated into the existing defensive walls of the bailey to improve the fortress’s resilience. Following Henry II’s reign, further stonework improvements were completed by 1202 under King John’s rule.

Ownership shifted in the early 13th century to the de Vieuxpont family, one of whom, Robert de Vieuxpont, expanded the castle’s fortifications to assert his authority in the region. After Robert’s death in 1228, the castle fell into some neglect until the 1260s when the Clifford family gained possession through marriage. The Cliffords undertook extensive repairs and enhancements, bringing the castle in line with architectural trends seen in northern England.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the Cliffords significantly refurbished Brough Castle. They rebuilt the eastern curtain wall and created Clifford’s Tower, a circular tower containing private living apartments. The family also modernized the castle’s living quarters with the addition of a first-floor great hall and a solar (a private chamber). The castle became involved in regional conflicts such as the Wars of the Roses, falling temporarily to Yorkist forces before being restored to the Cliffords in 1485.

A major setback occurred in 1521 when a fire broke out after a Christmas feast hosted by Henry Clifford. This blaze destroyed much of the habitable sections, reducing the castle to ruins for over a hundred years. Lady Anne Clifford, a notable member of the family, restored the castle between 1659 and 1661. Her work sought to return the castle to its former condition with traditional northern architectural elements, while also updating the accommodations to contemporary standards, including the installation of 24 fireplaces by 1665.

Despite this revival, another fire in 1666 left the castle uninhabitable again. Some of the buildings within the bailey were repurposed for court functions, but the castle itself was never fully rebuilt. During the late 17th and 18th centuries, materials were stripped from the structure to build elsewhere, hastening its decline. By around 1800 and again in 1920, parts of the keep’s southwest corner collapsed. In 1921, Brough Castle was given to the state and placed under the care of English Heritage, securing its status as a Grade I listed building and a scheduled monument. Archaeological excavations have been carried out intermittently since 1925, with major digs through the late 20th and early 21st centuries aiding its conservation. Ongoing erosion continues to pose a threat to the ruins.

Remains

Brough Castle occupies the northern section of the earlier Roman fort Verterae, covering about 1.2 hectares (3 acres). Its layout reflects its origins as a Norman motte-and-bailey castle, combining earthworks inherited from the Romans with medieval fortifications. The earliest stonework includes the foundations for the keep, originally constructed in the 12th century on a square plan. The keep was embedded into the bailey walls so it could directly defend the outer perimeter, serving as a powerful strongpoint.

This keep later became known as the “Roman Tower,” a name given by Lady Anne Clifford during her 17th-century restoration when she believed the structure dated back to Roman times. The tower remains a prominent feature of the site, though the southwest corner has suffered partial collapses around 1800 and 1920 due to masonry erosion.

During the early 14th century, the Clifford family built a circular structure called Clifford’s Tower within the castle complex. This round tower contained private apartments and shows architectural similarities to other northern castles such as Appleby Castle. At this time, the eastern curtain wall was rebuilt, and a large hall was constructed to provide a more comfortable and defensible living space.

Later in the 14th century, further work by Roger de Clifford involved rebuilding the south wall and replacing the original great hall with a first-floor hall and an adjacent chamber block, aligning with northern castle design preferences that favored square, angular towers rather than rounded southern styles. The old hall was converted into a solar, providing private accommodation, and the castle’s bailey was surfaced with cobblestones, improving its usability.

Around the mid-15th century, the castle’s gatehouse was strengthened with buttresses, and a new courtyard was added within the bailey, possibly under the direction of Thomas Clifford. These additions improved access control and may have provided extra defensive or domestic space.

During Lady Anne Clifford’s restoration efforts from 1659 to 1661, the castle saw the insertion of new windows and a ground-floor entrance into the keep, features that suited the standards of 17th-century comfort. Service quarters were added to support daily life, and by 1665 the castle contained 24 fireplaces, showing it was subdivided internally and extensively heated to accommodate residents comfortably.

Today, the stone walls of Brough Castle remain largely in ruins but retain key structural elements that outline its historic layout. Stabilization work by English Heritage has helped protect the most vulnerable parts, although natural erosion continues to threaten the masonry. Excavations since 1925 have revealed important information about the castle’s construction phases and have guided conservation plans, allowing visitors and scholars to appreciate the long history embedded in its walls.