Gjirokastra Old Town and Castle: A Historic Fortified Settlement in Southern Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.drtkgjirokaster.com

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Ottoman

Remains: City

Context

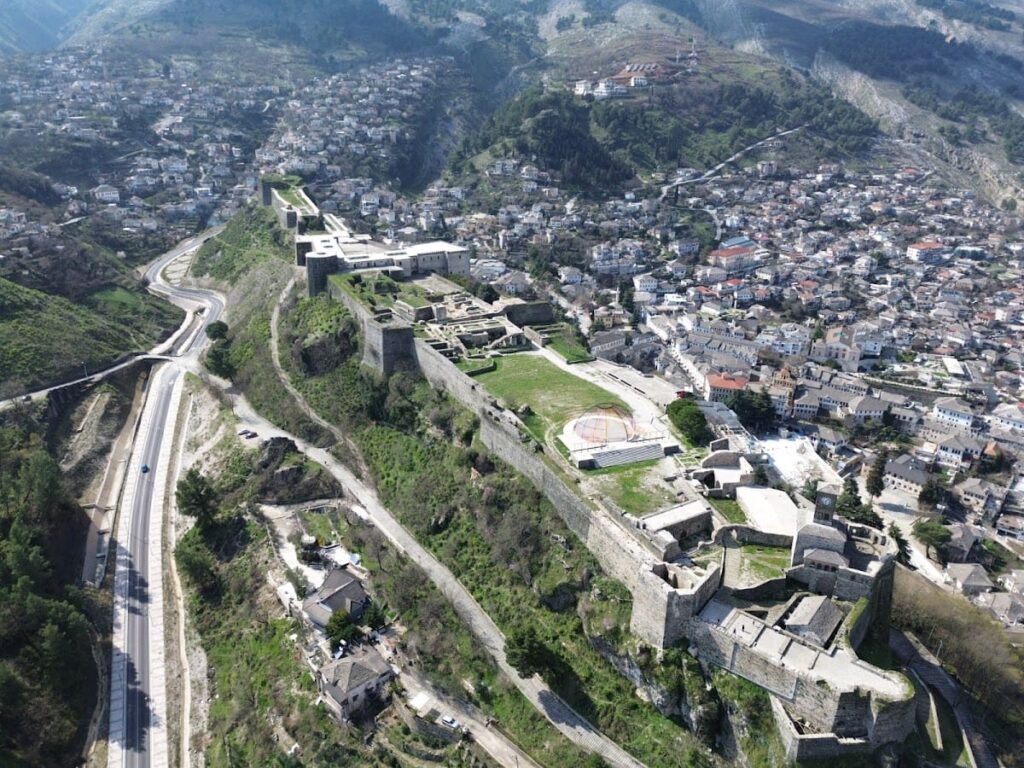

The Gjirokastra Old Town and castle are located in southern Albania, occupying a prominent hillside overlooking the Drino River valley. Positioned on the eastern slope of Mali i Gjerë mountain, the site commands a strategic vantage point approximately 200 meters above the valley floor. This elevated rocky ridge, extending about one kilometer in length, provided natural defensive advantages that shaped the settlement’s terraced urban development and fortification layout.

Archaeological and historical evidence demonstrates that the site has been continuously inhabited from late antiquity through the Byzantine and Ottoman periods into the modern era. The castle and town evolved as a fortified center with military, administrative, and residential functions. Preservation of original defensive structures and vernacular architecture remains notable.

History

Gjirokastra Old Town and its castle have a documented history of strategic importance rooted in their commanding position within southern Albania. The site’s development mirrors the shifting political and military control of Epirus and the western Balkans, from prehistoric occupation through Byzantine administration, medieval local rule, Ottoman governance, and into the modern Albanian state. The castle functioned as a fortified stronghold and administrative center, adapting to evolving military technologies and political structures while maintaining continuous habitation without clear abandonment phases.

Prehistoric and Hellenistic Period

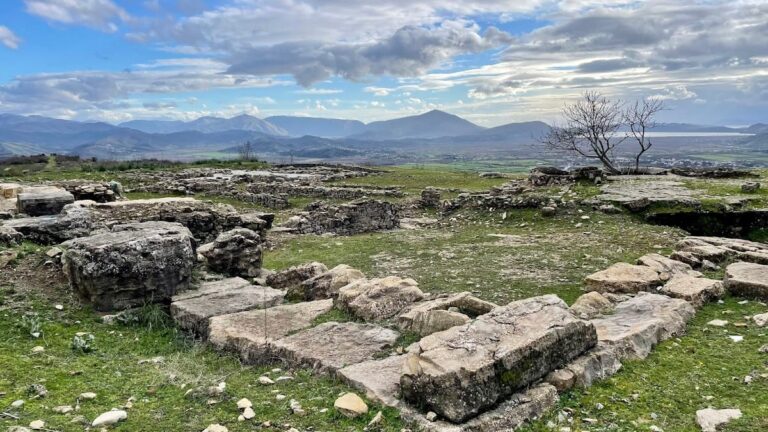

Archaeological investigations have established human presence on the castle’s rocky hill as early as the late Stone Age, approximately the 8th to 7th centuries BCE. Excavations conducted in 2025 uncovered structural remains of a tower dating to the 5th century BCE or the Hellenistic period, providing the earliest evidence of fortification at the site. This early defensive construction indicates the location’s strategic role in controlling access through the Drino valley during classical antiquity. However, due to the scarcity of written sources, the site’s political affiliations and broader role within Hellenistic territorial entities remain insufficiently documented.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period

During late antiquity, the region encompassing Gjirokastra was incorporated into the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, which sought to secure its western Balkan frontiers amid increasing external pressures. Archaeological data confirm continued occupation of the site, with fortifications and settlement structures exhibiting characteristics of Byzantine military architecture. The castle’s elevated position was integral to imperial defensive strategies aimed at controlling mountain passes and maintaining regional stability during periods of invasions and internal conflict. Although no epigraphic evidence explicitly records the site’s administrative status, the fortifications align with Byzantine efforts to reinforce frontier zones in Epirus and adjacent provinces.

Medieval Period (12th–15th century)

By the 12th or 13th century, Gjirokastra had developed into a fortified settlement governed by the local Zenebisi family, a regional aristocratic lineage. The fortress comprised multiple towers and served as a military and political stronghold within the fragmented medieval landscape of Epirus. In 1417, the Zenebisi successfully resisted an Ottoman siege during the summer months, demonstrating the fortress’s defensive capabilities. However, the following year (1418), the castle capitulated, marking the onset of Ottoman control. The fortress formed the nucleus around which the town expanded, particularly with the development of the Varosh suburb on the eastern slopes during the 15th century. Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi’s 1670 account describes the castle as containing approximately 200 multi-story stone houses and a mosque, reflecting a densely inhabited and architecturally distinctive fortified community.

Ottoman Rule (15th century–early 20th century)

Following the Ottoman conquest, the fortress underwent substantial renovation and enlargement, notably under Sultan Bayezid II, who commissioned the construction of the first mosque within the castle walls. The site’s strategic importance increased as it became a military and administrative center within the Eyalet of Rumelia. In the early 19th century, Ali Pasha of Janina initiated extensive rebuilding and expansion of the fortress between 1811 and 1812, completing the works in approximately eighteen months. He also engineered a water supply system extending nearly ten kilometers, terminating in an aqueduct that supplied the castle’s cisterns; remnants of this aqueduct remain visible above the town. The castle complex measures roughly 500 meters in length and up to 90 meters in width, featuring seven towers and multiple defensive walls adapted to the rugged terrain. Interior elements include vaulted passageways, a former prison, a Bektashi türbe containing graves of 16th- and 17th-century religious leaders, and a 19th-century clock tower, whose mechanism was installed in the 1960s.

20th Century to Present

In 1932, under King Zog’s administration, the castle’s prison was formally established. During World War II, the facility was utilized by Italian and German occupying forces and subsequently held political prisoners during the communist regime until its closure in 1968. Since that year, the castle has served as the venue for the National Folklore Festival, a recurring cultural event celebrating Albanian traditions. From 1971 onward, the castle’s casemates have housed the National Weapons Museum, exhibiting artillery, armored vehicles, and artifacts related to the communist resistance against Nazi occupation, including a Lockheed T-33 jet that made an emergency landing in 1957. Since 2012, the castle also contains the Gjirokastra Museum, dedicated to the history of the city and its surrounding region. These developments have reinforced the castle’s role as a cultural and historical landmark within Albania.

Remains

Architectural Features

The Gjirokastra Old Town and castle occupy a steep rocky ridge approximately one kilometer in length on the eastern slope of Mali i Gjerë, rising about 200 meters above the Drino River valley. The castle fortress extends roughly 500 meters longitudinally, with widths varying from approximately 90 meters at its broadest to as narrow as ten meters. The town’s urban fabric is terraced, conforming to the steep topography. Construction predominantly employs local stone masonry, integrating defensive walls and residential buildings into the natural terrain. The architecture reflects a primarily military and residential character, with fortifications dominating the castle and vernacular Ottoman-era houses populating the town below. The settlement exhibits continuous growth from late antiquity through the Ottoman period, with notable expansions in the 15th and early 19th centuries.

Building techniques include vaulted chambers within the castle and multi-story stone houses featuring turrets (kullë), characteristic of Balkan Ottoman domestic architecture. The castle’s defensive walls incorporate seven towers and multiple gates aligned along the ridge, with vaulted passageways extending the fortress’s length. The town’s houses typically have elevated ground floors, with upper floors designed for seasonal living. Religious structures such as an 18th-century mosque and two churches from the same century are preserved within the urban fabric near the bazaar area.

Key Buildings and Structures

Gjirokastra Castle

The castle is a hilltop fortress with origins traced to the 5th century BCE or Hellenistic period, as confirmed by 2025 excavations uncovering remains of an early tower. The fortress is divided into four principal sections: the western quarter contains vaulted chambers constructed after 1811 and a garden with a Bektashi türbe housing graves of 16th- and 17th-century religious leaders; the central section includes the main entrance and the former prison; the third section comprises large open spaces currently used as a festival stage, situated above extensive cisterns; and the easternmost part features a bastion, a secondary entrance, and the 19th-century clock tower, whose mechanical clock was installed in the 1960s.

The fortress includes seven towers and originally featured vaulted passageways running its entire length. A third gate existed on the south side opposite the main entrance. The castle’s walls and towers are constructed of local stone, with masonry techniques evolving through successive phases. After the Ottoman conquest in 1418, the fortress was renewed and expanded under Sultan Bayezid II, who also commissioned the first mosque within the castle walls. Major reconstruction and enlargement occurred between 1811 and 1812 under Ali Pasha of Janina, who completed the work in about eighteen months. He also engineered a water supply system approximately ten kilometers long, ending in an aqueduct (demolished in the 1930s) that fed the castle’s cisterns; a surviving bridge from this system remains above the town.

The castle’s prison was formally established in 1932 under King Zog. It was used by Italian and German forces during World War II and later held political prisoners during the communist regime until its closure in 1968. Since 1971, the fortress’s casemates have housed the National Weapons Museum, displaying artillery, armored vehicles, and relics of the communist resistance against Nazi occupation, including remains of a Lockheed T-33 jet that made an emergency landing in 1957. Since 2012, the castle also contains the Gjirokastra Museum, dedicated to the city and region’s history.

Ottoman-era Houses with Turrets (Kullë)

The town contains numerous two-story stone houses with turrets, locally known as kullë, primarily dating from the 17th century, with some examples from the early 19th century. These houses feature an elevated ground floor, a first floor used for winter living, and a second floor for summer use. Interiors, especially guest rooms, are decorated with painted floral motifs. The kullë are constructed with stone masonry and wooden elements, reflecting vernacular Balkan architectural traditions adapted to the local climate and terrain.

Religious Buildings

Within the town, an 18th-century mosque and two churches from the same century remain preserved. The mosque is built of stone with typical Ottoman architectural features, including a minaret and prayer hall. The churches are constructed in local stone and retain structural elements consistent with 18th-century ecclesiastical architecture. These religious buildings are integrated into the urban fabric near the bazaar area, illustrating the coexistence of Muslim and Christian communities.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at the castle in 2025 uncovered remains of a tower dating to the 5th century BCE or Hellenistic period, confirming early fortification efforts. Artifacts from late antiquity and Byzantine periods include fortification elements and settlement structures consistent with military architecture. Ottoman-period material culture is abundant, including architectural fragments, domestic objects, and religious artifacts.

Finds include a variety of pottery types, both locally produced and imported, recovered from domestic and public contexts. Inscriptions are limited but include dedicatory texts related to the castle’s religious and administrative functions. Coins from various Ottoman rulers have been found, supporting the site’s continuous occupation through the early 20th century. Tools and domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels have been recovered from residential quarters, illustrating aspects of daily life. Religious artifacts include items associated with the Bektashi türbe and mosque complexes.

Preservation and Current Status

The castle’s defensive walls, towers, and vaulted chambers are generally well-preserved, with some sections restored during 20th-century conservation efforts. The Bektashi türbe and garden area have been stabilized to protect the graves and masonry. The former prison building remains intact, though no longer in use. The clock tower structure was added in the 1960s and houses a mechanical clock mechanism installed at that time.

Many of the Ottoman-era kullë houses retain original stone walls and turrets, though some have undergone restoration to preserve structural integrity. The mosque and churches from the 18th century are maintained but show varying degrees of wear. Conservation projects have focused on stabilizing masonry and preserving traditional building techniques. The castle’s water supply system is largely demolished, with only a bridge surviving above the town. The site faces environmental challenges such as erosion and vegetation growth, as well as past impacts from illegal construction in the late 20th century. Albanian cultural heritage authorities continue to oversee preservation and management.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of the castle and surrounding old town remain unexcavated or only partially studied. Surface surveys and historic maps indicate potential buried remains beneath the town’s terraced houses and in peripheral areas of the fortress. Modern urban development limits excavation opportunities in some sectors. Future archaeological work is planned but constrained by conservation policies and the need to balance preservation with ongoing habitation. Non-invasive geophysical studies have been proposed to identify subsurface features without intrusive excavation.