Requesens Castle: A Medieval Fortress in La Jonquera, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: www.fincaderequesens.cat

Country: Spain

Civilization: Medieval European, Modern

Site type: Domestic

Remains: Palace

History

Requesens Castle is a medieval fortress situated in the municipality of La Jonquera, Spain. It was originally constructed by the Counts of Roussillon during a time marked by territorial disputes in the late 10th and early 11th centuries.

The castle first appears in written records between 1040 and 1071 in a grievance memorial where Count Ponç I of Empúries objected to the building of the fortress on lands claimed by his county. This early conflict was part of a broader struggle for control in the region following the division of territories between the counties of Empúries and Roussillon at the end of the 10th century. Over the next decades, agreements dated 1075, 1085, and 1121 formally recognized the Counts of Roussillon’s lordship over Requesens, emphasizing its significance. Throughout the 12th century, the castle was closely tied to the ruling family of Roussillon who often appointed castellans or lords from their own lineage, underscoring the site’s strategic importance.

The 12th century also saw Requesens Castle become a focal point in regional conflicts. Notably, during the “war of Requesens” from 1047 to 1072, Count Ponç II of Empúries captured the fortress amid ongoing feuds, including alliances formed between the Rocabertí viscounts of Peralada and the Counts of Roussillon. In 1172, after the Count of Barcelona took control of Roussillon, King Alfonso II relinquished his claims on Requesens in favor of the Count of Empúries, who then exercised full authority over the castle.

By the late 12th and 13th centuries, several individuals bearing the surname Requesens acted as lords or castellans, among them Arnau de Requesens (circa 1181) and Guillem de Requesens (post-1262). These family members likely served as predecessors of the noble Requesens family later ennobled as Counts of Palamós. The castle endured military pressures in the late 13th century; it was besieged by French forces during the 1285 crusade against the Crown of Aragon but resisted capture. A few years later, in 1288, a French army allied with James II of Mallorca briefly occupied and plundered the stronghold.

Ownership shifted again in the early 14th century when Peter I of Empúries purchased the lordship from the Castellnou family, consolidating his domain. The Counts of Empúries retained control until 1402 when the county returned to the crown. In 1418, King Alfonso the Magnanimous granted the castle to the Rocabertí viscounts, who maintained possession until the late 19th century.

Between 1893 and 1899, the castle underwent a comprehensive reconstruction to serve as a summer residence for Tomàs de Rocabertí-Boixadors Dameto, the last resident Count of Peralada, and his sister Joana-Adelaida. The renovation embraced neo-medieval architectural principles while respecting the original fortress design. During the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the castle suffered looting. In the post-war years, military use altered the interior with installations such as kitchens and a hospital, causing damage to the structure. Since 1955, it has been privately owned by industrialists. Despite partial vandalism and disuse, the castle remains protected as a Cultural Asset of National Interest under Spanish and Catalan heritage legislation.

Remains

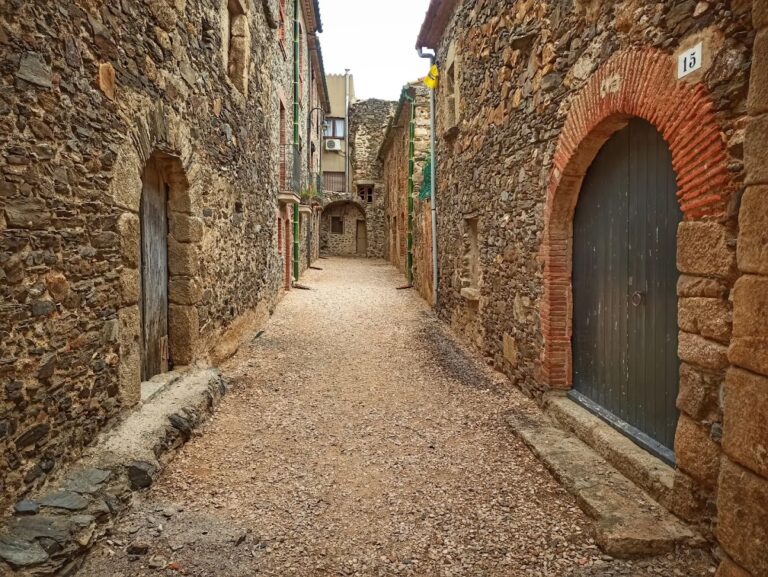

Requesens Castle is set on a hilltop that overlooks the southern valleys of Mount Neulós, strategically positioned to control access routes into Spain. Its layout features a series of three fortified enclosures incorporating both round and square towers, defensive portals, battlements, and machicolations, which are openings in the walls used for defense. The castle’s principal building material is local granite stone, a tradition preserved during the 19th-century reconstruction, which adhered closely to the original medieval footprint, making much of the rebuilt and ancient fabric visually indistinguishable.

Within the upper enclosure, historically referred to in the 13th century as the greater or upper fortress, several medieval elements have survived. These include portions of bastion walls, a square tower on the castle’s north side, and segments of the gate structure leading into this section. These remains date from between the 12th and 14th centuries, offering valuable insight into the castle’s original defensive design.

The lower enclosure encompasses a sizeable chapel dedicated to the Virgin of Providence. This chapel integrates Romanesque components salvaged from nearby buildings, such as arches taken from the portal of the former Santa Maria de Requesens church, combined with French artistic elements like a sculpted tympanum and reliefs above the entrance door. These features reflect both regional and trans-Pyrenean cultural influences merged during its construction or renovation.

Additional service buildings occupy the lower enclosure, including stables and kitchens. One space within this area was adapted in the mid-20th century to serve as a military hospital. The second, smaller enclosure houses an attractively fortified gate that contributed to the castle’s layered defense system.

The noble or upper enclosure contains rooms where parts of the original flooring remain visible, decorated with the heraldic emblem of the Rocabertí family, former holders of the castle. A large hall boasts a stone fireplace and window shutters with theatrical designs, a distinctive detail that highlights the home’s residential aspect during later periods. The highest point is marked by a round watchtower, although it is currently inaccessible to visitors.

Surrounding the castle, landscaping efforts during the 19th century introduced a mixture of native and exotic plants to enhance the site’s visual appeal. Photographic documentation made before and throughout the reconstruction, including images taken by Count Tomàs de Rocabertí himself, provide exceptional records of the castle’s condition prior to restoration.

The military presence in the mid-1900s led to modifications and damage, notably affecting interior spaces and parts of the battlements. Today, while the castle’s interior primarily reflects the 19th-century mansion phase and is partially dismantled, the castle’s external form continues to display its rich historic layers. Safety concerns have led to some areas being closed off, preserving what remains for future study and appreciation.