Chlemoutsi Castle: A Medieval Fortress in Greece

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: odysseus.culture.gr

Country: Greece

Civilization: Crusader, Ottoman

Remains: Military

History

Chlemoutsi castle is located in the municipality of Andravida-Kyllini, Greece. It was built in the early 13th century by the Frankish rulers of the Principality of Achaea, a crusader state established in the Peloponnese after the Fourth Crusade.

The castle’s construction took place between 1220 and 1223 under Geoffrey I of Villehardouin, the Prince of Achaea. Its founding was closely linked to a conflict with the local church authorities, who refused to contribute soldiers for the prince’s military needs. To fund the castle’s construction, Geoffrey confiscated property from the church, highlighting the tense relationship between secular and religious powers at the time. Chlemoutsi was intended as the principal fortress of the principality, located near the capital of Andravida and the main port of Glarentza. From its elevated position, it controlled the fertile plains of Elis, a significant agricultural region.

Throughout its history, Chlemoutsi was never subjected to a siege, reflecting either its strong defenses or its strategic position. Instead, it served at times as a prison for important prisoners, including Byzantine generals captured around 1263 during military conflicts between Latin and Byzantine forces in the region.

Following the death of William II Villehardouin in 1278, ownership of the castle passed to his widow, Anna Komnene Doukaina. In the early 14th century, the site became tied to complex political alliances and conflicts involving the Angevins—rulers from the Kingdom of Naples—and local nobility. For instance, in 1314, a marriage between Margaret Villehardouin’s daughter and Ferdinand of Majorca brought Chlemoutsi into the center of rival claims and disputes over the principality.

In 1427, Chlemoutsi came under Byzantine control as part of a dowry given to Constantine Palaiologos, later the last Byzantine emperor. Constantine used the castle as a military base in his campaigns against Latin-held territories in the Peloponnese. This period marked one of the last Byzantine efforts to regain influence in the region before the advancing Ottoman threat.

The Ottoman Empire conquered the castle in 1460. They made minor changes to adapt it for artillery use but did not significantly alter its medieval character. The fortress saw brief Venetian occupation between 1463 and 1479, and in 1620 it was attacked by the Knights of Malta, indicating its continuing strategic importance in regional conflicts.

During Venetian rule from 1687 to 1715, Chlemoutsi served primarily as a fiscal center though it remained sparsely inhabited. Plans to dismantle the castle in 1701 were proposed but never carried out. By the early 19th century, the fortress was largely abandoned. In 1825, during the Greek War of Independence, Ibrahim Pasha’s Egyptian forces intentionally damaged part of its walls, ensuring it could not be used by Greek rebels.

Today, Chlemoutsi stands as a preserved historical monument reflecting the complex military and political history of medieval Greece.

Remains

Chlemoutsi castle occupies a small plateau roughly 226 meters above sea level near the present-day village of Kastro-Kyllini. The castle’s layout centers on a large hexagonal keep measuring about 90 meters across east to west and 60 meters north to south, surrounding an inner courtyard approximately 61 by 31 meters. This main structure was built in the early 13th century and showcases predominantly French Romanesque architectural style from the 12th century, blended with some Byzantine features such as chamfered impost blocks—these are slightly bevelled supports where arches begin. The walls of the keep contain two levels of halls: the lower floors open onto the courtyard through arches, while the upper floors feature vaulted galleries with ovoid barrel vaults made from finely dressed poros limestone, reinforced by transverse arches spaced every seven to ten meters.

The keep’s round towers, each about five meters in diameter and set on square bases, flank its western side. Of these, the southern tower is mostly in ruins, with much of the damage dating to the 19th century, likely from wartime cannon fire. The eastern and southern sides of the fortress do not have towers, as they rely instead on steep natural slopes for protection. Originally, the roof was sloped or gabled with a parapet and a walkway known as a chemin de ronde. This was later replaced with a flat terrace bordered by an inner parapet, complete with some battlements added during Ottoman times. Unlike typical artillery fortifications, there are no gun emplacements on the roof.

Entry into the keep is gained through its northern side via a vaulted passage that runs between two gates leading from the outer courtyard. Outside the keep lies an outer ward, or forburg, positioned to the west. This was enclosed by an irregular polygonal curtain wall constructed from limestone. Ottoman additions to this wall include buttresses for support, merlons (the solid upright sections of battlements), and artillery bastions adapted to early gunpowder weapons. The main gate, situated on the northwest side, was originally defended by a portcullis—a heavy, vertically sliding grille—and a recessed section of the wall that was later filled in by the Ottomans.

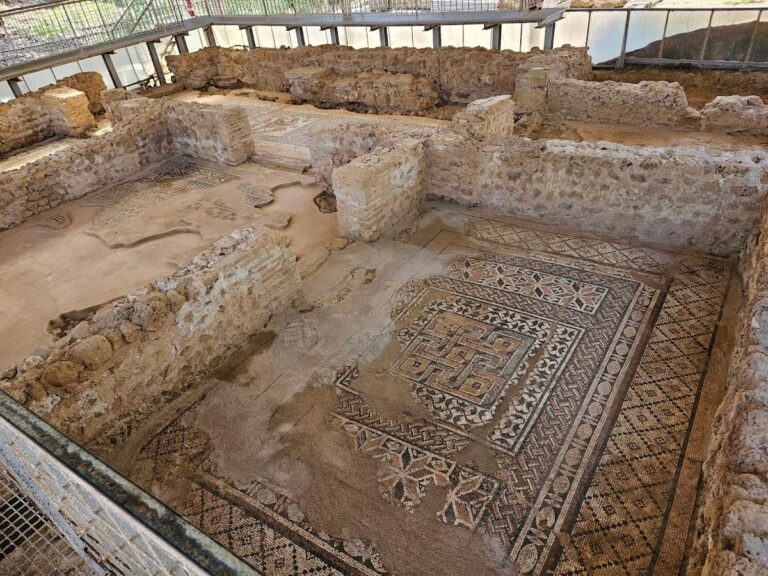

Buildings were constructed immediately against the curtain wall from the time of the castle’s initial construction. Archaeological evidence such as foundations, fireplaces, and lancet-shaped windows—which are tall, narrow windows with pointed arches—attest to these structures’ presence. One building near the main gate remains well preserved, allowing insights into the castle’s domestic or administrative functions.

The curtain wall includes small secondary gates, called posterns, and staircases leading up to the wall walk, allowing defenders to move along the ramparts. On the southwestern corner, an Ottoman artillery bastion and tower were added, reflecting adaptations to the evolving demands of warfare. Signs of repairs and a breach caused by cannon fire during Ibrahim Pasha’s assault in 1825 remain visible, providing tangible proof of the castle’s violent history.

Overall, Chlemoutsi’s rapid construction within a few years resulted in a fortress retaining a cohesive Frankish architectural character, with relatively few alterations across its centuries of use. Its preserved state offers a clear window into medieval fortification design in the Peloponnese.