Whorlton Castle: A Norman Motte-and-Bailey Fortress in Northallerton, UK

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

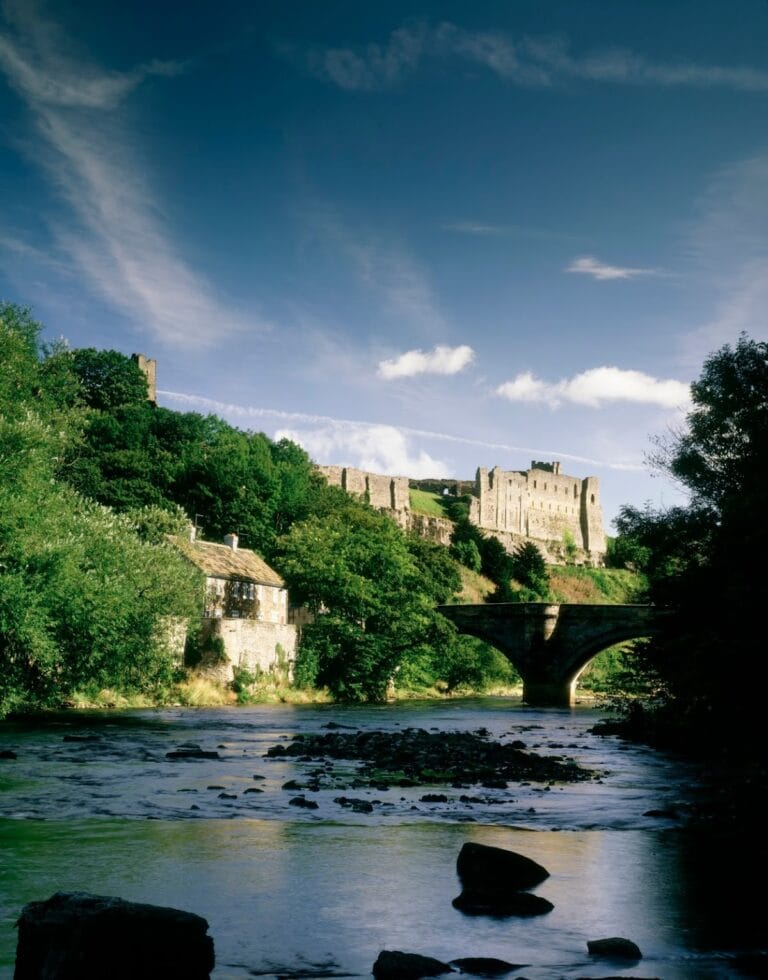

Whorlton Castle, located near the village of Whorlton in the municipality of Northallerton, United Kingdom, was constructed by the Normans during the early 12th century. Its position was strategically chosen to oversee an important roadway connecting Thirsk and Stokesley, situated on the western edge of the North York Moors.

Originally, the estate belonged to Robert, Count of Mortain, who was a half-brother of William the Conqueror and held it during the Domesday survey of 1086. Ownership later passed to the de Meynell family, who most likely erected the first castle structure, a wooden fortress utilizing the motte-and-bailey design. This initial castle was built on a sizable, roughly rectangular earthen mound, known as a motte, measuring approximately 60 by 50 meters.

By the mid-14th century, records from 1343 indicate the castle had fallen into disrepair or was dismantled, though habitation persisted into the early 1600s. Around the same era, the property transferred through marriage to John Darcy. Darcy undertook major reconstruction, leveling the motte to make way for a new stone keep and a significant gatehouse on the eastern side. While a curtain wall may have once enclosed the compound, no conclusive evidence survives today, likely due to later removal of stone.

The Darcy family maintained possession until 1418, when the estate passed to Elizabeth Darcy and her husband Sir James Strangeways. The Strangeways family held the castle until 1541, after which inheritance conflicts led the property to revert to royal ownership under the Crown. King Henry VIII granted the castle and lands to Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox. His son, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, is historically associated with Whorlton through marriage negotiations with Mary, Queen of Scots, though their contract was formalised elsewhere.

In the late 16th or early 17th century, the Lennox family added a two-storey residence adjoining the northwest end of the gatehouse. This addition is depicted in a 1725 sketch but has since vanished, leaving only the outline of its roofline visible on the gatehouse walls. By 1600, the castle was described as old and in a state of decay. Ownership passed to Edward Bruce in 1603, and the estate remained with the Bruce family until the late 19th century. At that time, James Emerson acquired the property and oversaw stone removal from the site in 1875, which supplied material for the nearby Swainby village church.

In the mid-20th century, Osbert Peake, 1st Viscount Ingleby, purchased the site to include in a shooting estate. Whorlton Castle was designated as a Grade I listed building in 1928, acknowledging its significance. During the 1960s, structural repairs were carried out on the gatehouse by the Ministry of Works. Despite conservation efforts and early 21st-century proposals considering residential use or community management for the gatehouse, attempts at conversion did not come to fruition following the collapse of the organization responsible for those plans.

Remains

Whorlton Castle presents a complex layout characteristic of Norman motte-and-bailey fortifications that evolved through successive phases. The original structure included a large earthen mound known as a motte, roughly rectangular in form and measuring around 60 by 50 meters. This mound was encircled by a substantial dry ditch up to 20 meters wide and five meters deep, with an outer bank rising as high as 2.5 meters. Most of this ditch remains visible today, except in one area overlain by a modern roadway.

Situated on the eastern side of the motte is the gatehouse, the most well-preserved element of the castle. Dating to the mid-14th century, this sandstone building rests on a rectangular plan measuring roughly 18 by 10 meters. It is constructed from finely cut sandstone blocks in a technique known as ashlar masonry. The gatehouse survives roofless and without flooring, but its walls stand between six and eight and a half meters tall, with thickness varying from approximately 1.7 to 2.3 meters.

This structure features two large entrances with segmental arches facing opposite sides, each measuring about three meters wide and 3.3 meters high. Flanking these gateways are narrow, cross-shaped windows often associated with defensive and lighting functions. Above the eastern, main entrance are carved shields set within pointed or cusped panels. The central shield bears the Darcy family coat of arms, to its right the Meynell arms, and to the left those of the Gray family. Above these is a single shield showing the combined, or impaled, arms of Darcy and Meynell, highlighting key family alliances forged through marriage.

The gatehouse originally contained heavy wooden or metal portcullises, which are defensive grilles that could be lowered to secure the entrance. Grooves for operating these portcullises remain visible in the walls, indicating they were managed by winches embedded within. Internally, part of the vaulted central passageway survives. Flanking this passage were large chambers, along with smaller rooms built within the thickness of the walls, probably serving as guardrooms.

The upper floor of the gatehouse once featured a great hall spanning its entire length, with fireplaces evident on both the ground and first floors, marking heated living and working spaces. Access to the upper stories was provided by a spiral staircase located in a projecting tower on the northwest wall. This staircase was entered through a round-headed doorway on the exterior side rather than from inside the gatehouse.

Attached to the northwest wall of the gatehouse was a two-storey house added in the late 16th or early 17th century. While this building no longer stands, its former roofline remains visible on the gatehouse walls, providing a faint outline of its position and scale.

On the opposite end of the bailey, about 22 meters west of the gatehouse, lay the castle’s stone keep. Only fragments remain, chiefly parts of vaulted Norman cellars or storage areas underneath the original structure. The largest cellar measures approximately nine by four meters. These underground chambers were used as pigsties during the mid-19th century and are now overgrown but still accessible.

The surrounding landscape contributes to the site’s historical narrative. Medieval cultivated fields bear visible plough marks, and two late medieval ornamental gardens, each roughly 40 by 20 meters, survive as earthwork enclosures with low banks around one meter in height. A large rectangular pond measuring 190 by 20 meters and up to three meters deep lies nearby; while it may have functioned as a fish pond, its considerable size makes this uncertain. To the south of the castle grounds, a deer park was established, historically linked to royal hunting activities.

Today, the castle, its landscape features, and the deserted village of Whorlton form a scheduled ancient monument, recognizing their archaeological importance. The gatehouse remains listed on the Heritage at Risk Register due to ongoing deterioration from weather exposure and acts of vandalism, despite past repair efforts.