Pinara: An Ancient Lycian City in Turkey

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

Pinara Ancient City is situated within the boundaries of Seydikemer municipality in modern Turkey. It was originally established by the Lycians, an ancient civilization that thrived in southwestern Anatolia.

The city began as a colony of Xanthos, one of the principal Lycian centers. Its earliest name appears as Artymnesus or Artymnesos in historical records, while the Lycian name “Pilleñni” or “Pinale” likely derives from the word meaning “round,” a reference to the distinctive rounded rock formation on which the city was built. Pinara held an important place in Lycian culture and politics, evidenced by its membership in the Lycian League, a federation of city-states where Pinara was granted three votes, reflecting its considerable influence.

Pinara’s connection to Lycian mythology and the Trojan War is found in the local cult of Pandarus, a Lycian hero mentioned in Homeric epics, suggesting the city as his place of origin. This blend of history and legend marks Pinara as both a cultural and religious center in the region.

In 334 BCE, during Alexander the Great’s campaign in Anatolia, Pinara surrendered to his forces without resistance. Following the decline of Lycian autonomy, the city came under Pergamene rule. When Attalus III, the last king of Pergamum, died in 133 BCE, he willed his kingdom to the Roman Republic, thereby integrating Pinara into the Roman domain.

Under Roman control, Pinara experienced a period of prosperity and development. However, the city faced significant challenges from natural disasters. Earthquakes struck twice with destructive force in 141 CE and again in 240 CE. After the earthquake in 141 CE, prominent Lycian benefactor Opramoas provided financial support for the restoration of public buildings, helping Pinara recover and maintain its urban life.

By the 4th century CE, Christianity had established a foothold here. Records indicate that five bishops from Pinara attended ecclesiastical councils between the 4th and 9th centuries, signaling the city’s importance in early Christian administration. Additionally, Pinara is linked to the legendary figure of Saint Nicolas of Myra, traditionally believed to have been born nearby, reflecting its lasting religious association.

Despite its resilience and rich history, Pinara faced repeated invasions and turmoil in the 9th century, leading to its eventual abandonment. Centuries later, during the 19th century, Sir Charles Fellows identified and documented the ruins of Pinara, highlighting its extensive tombs and exceptionally preserved theater, which brought renewed scholarly attention to the ancient site.

Remains

The ruins of Pinara unfold upon a vast, rounded rock formation, consistent with the city’s name. This natural stone massif commands the landscape, with the ancient city’s layout oriented along a north-south axis on sloping terrain descending from west to east, approximately 360 meters above sea level and ending in a flat valley area.

Pinara’s defenses include city walls constructed using Cyclopean masonry, a technique involving massive, irregular stones fitted together without mortar. Notably, some gateways incorporate three enormous stones each, creating formidable entrances that have preserved their monumental scale through time. Above and below lie two acropolises, or fortified upper town areas, signifying strategic points in the city’s design.

Central to public life was the agora, an open marketplace, which connected via a primary street roughly 4.2 meters wide. This street ran southward from the agora and the odeon, a small auditorium for performances or gatherings, flanked by buildings interpreted as shops or public institutions. It led to a large paved space, likely functioning as a viewing terrace with wide views to the south.

The city’s theaters are among its best-preserved structures. The main theater retains all its stone seats arranged in rows angled toward the stage area. Several original doorways remain standing intact, allowing a vivid sense of the venue’s original form and scale. Adjacent to the theater is a bathhouse, consistent with Roman urban amenities. The theater and bathhouse occupy the terrain as it slopes down to about 300 meters elevation on the eastern side.

Pinara’s religious and social architecture includes several temple remains though specific dating details are scarce in the records. The basilica, an early Christian church building measuring approximately 19.35 meters long (including its semicircular apse) and 14.40 meters wide, features a three-nave rectangular floor plan oriented east-west. Its remains are partly buried beneath soil and vegetation but testify to the city’s Christian period and liturgical functions.

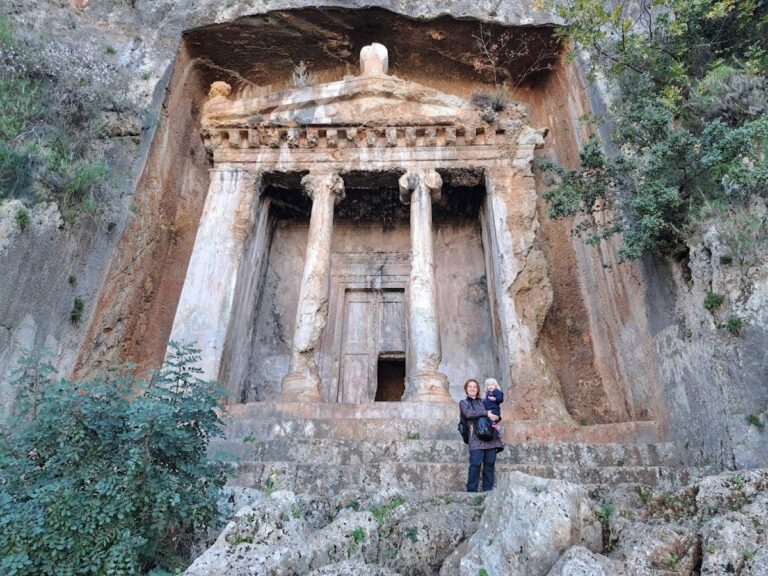

The extensive necropolis surrounds the city, especially on cliffs and steep slopes. Various tomb types populate the burial areas. Among these, large rectangular rock-cut tombs are carved into the steep eastern face of the mountain, while numerous richly sculpted rock tombs feature both Lycian and Greek inscriptions, revealing linguistic and cultural interchange. One tomb identified as “royal” stands out among the funerary monuments for its size and elaborate decoration.

Columns found at Pinara show a distinctive heart-shaped cross-section rather than the more common circular form, marking a unique architectural detail. This feature can be seen in surviving structures and contributes to the city’s individual artistic character.

Together, the ruins of Pinara offer a rich mosaic of Lycian, Hellenistic, Roman, and early Christian architectural elements, preserved on a dramatic natural setting near the modern village of Minare, about 45 kilometers from the coastal town of Fethiye in Turkey.