Ostia Antica: The Ancient Roman Port City at the Mouth of the Tiber

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.ostiaantica.beniculturali.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Ostia Antica is situated near the modern Tyrrhenian coastline, approximately 25 kilometers southwest of central Rome, Italy. Positioned at the mouth of the Tiber River within the municipality of Rome, in the area now known as Viale dei Romagnoli, the site occupies a strategic location where riverine and maritime routes converge. The surrounding flat alluvial plains and proximity to the river’s delta facilitated access to both inland and sea-based transportation networks, shaping the settlement’s development over time.

Archaeological investigations have established that Ostia originated as a Roman military and commercial outpost in the late 4th century BCE. The site expanded through the Republican and Imperial periods, reaching its zenith in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Occupation persisted into Late Antiquity, with evidence of gradual decline by the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Environmental factors, notably the silting of the Tiber’s harbor and alterations in watercourses, played a significant role in the site’s eventual abandonment, as supported by both archaeological stratigraphy and historical sources.

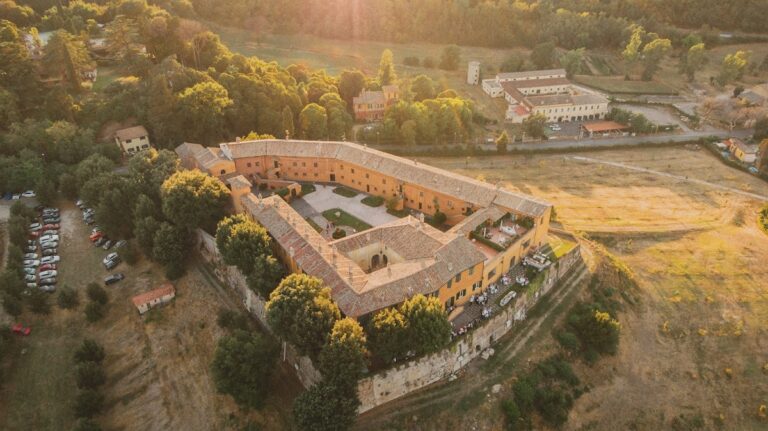

Ostia Antica is recognized as one of the most extensively preserved ancient Roman urban sites. Systematic excavations initiated in the late 19th century have revealed a comprehensive urban plan, including public edifices and residential quarters. Ongoing conservation efforts by Italian heritage authorities have maintained the site as an open-air archaeological park, enabling scholarly research and controlled public visitation while safeguarding its structural remains from environmental deterioration.

History

Ostia Antica’s historical trajectory reflects its transformation from a Roman military stronghold to a principal imperial port, followed by decline in Late Antiquity. Its location at the Tiber River’s mouth established it as a critical nexus between Rome and Mediterranean maritime trade. The site’s evolution mirrors broader political, economic, and infrastructural developments within the Roman Republic and Empire, as well as environmental changes that redirected commercial activity to adjacent harbors.

Early Roman Period and Foundation (7th–4th century BCE)

According to Roman tradition, Ostia was founded in the early 7th century BCE by Ancus Marcius, Rome’s fourth king, to secure control over the Tiber’s mouth and the surrounding salt marshes. Some ancient authors, including Polybius, suggest an even earlier origin linked to religious sanctuaries, possibly dedicated to Vulcan, predating Roman colonization. Archaeological evidence confirms the earliest Roman presence from the late 4th century BCE, marked by the construction of a fortified castrum composed of large tufa blocks. This military installation enclosed a rectangular area with defensive walls and corner towers, designed to protect the river entrance and the Lazio coastline. The castrum’s strategic function is further underscored by Ostia’s exemption from military conscription during the Second Punic War, indicating its role as a naval base supporting Rome’s fledgling fleets.

Late Republican Period (2nd–1st century BCE)

During the late Republic, Ostia transitioned from a military outpost to a thriving commercial emporium. The city was enclosed by substantial defensive walls constructed in opus reticulatum masonry, featuring three principal gates: Porta Romana, Porta Laurentina, and Porta Marina. These fortifications delineated the urban boundary and regulated access. Ostia served as Rome’s primary maritime port, facilitating the importation of essential commodities such as grain and salt. The city’s strategic importance is evidenced by its involvement in the civil war between Marius and Sulla, during which it was sacked by populares forces and subsequently rebuilt under Sulla’s direction. Archaeological and epigraphic data reveal diverse burial grounds outside the city walls, reflecting a heterogeneous population comprising both common citizens and affluent elites.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–3rd century CE)

The Imperial period represents Ostia’s apex in urban development and economic activity, coinciding with Rome’s consolidation as a Mediterranean empire. Under Augustus, the city underwent extensive public works, including the construction of a Roman theatre and the renovation of the forum, enhancing its civic stature. To address persistent silting at the river harbor, Emperor Claudius initiated the construction of a large artificial harbor approximately four kilometers north of Ostia. This harbor encompassed a 150-hectare basin with curved piers, docks, and a multi-storey lighthouse situated on an artificial island, facilitating the accommodation of large cargo vessels. Trajan further expanded port infrastructure by erecting a hexagonal basin of 33 hectares, designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, which significantly increased docking capacity. This complex included extensive warehouses (horrea), guild halls (scholae), and an imperial palace intended for high-ranking visitors. Ostia’s population peaked at an estimated 50,000 inhabitants, residing predominantly in multi-storey apartment buildings (insulae). The urban fabric featured public baths, markets (macellum), and temples such as the Capitolium, dedicated to the Capitoline Triad. The Boacciana Tower, constructed in the 2nd century CE on the Tiber’s left bank near the sea, functioned as a lighthouse or guard tower, underscoring continued control over river access.

Late Imperial and Late Antique Period (3rd–6th century CE)

From the mid-3rd century CE onward, Ostia’s commercial prominence diminished as activity shifted to the nearby port of Portus. Literary and archaeological evidence indicate progressive urban decline, with the Tiber’s harbor becoming increasingly unnavigable and the via Ostiense falling into disrepair by the 6th century. Christianization is attested by the construction of religious edifices such as the basilica at Pianabella and the Church of St. Herculanus, which incorporated reused Roman materials and were situated near suburban cemeteries. Ostia functioned as a bishopric from the 3rd century, reflecting its ecclesiastical significance despite demographic contraction. The city endured multiple sackings during the 5th century by Visigoths under Alaric, Ostrogoths under Vitiges, and later Arab raids, which severely disrupted maritime trade and contributed to its abandonment by the 9th century.

Medieval Period (6th–15th century CE)

Following abandonment, Ostia’s ruins were extensively quarried for building materials throughout the Middle Ages, a common fate for Roman urban centers. The Boacciana Tower underwent restorations in the 12th and early 15th centuries under Popes Innocent VII and Martin V, serving variously as a lighthouse, guard tower, and papal customs post. The flood of 1557 altered the Tiber’s course, diverting the river away from Ostia and diminishing the strategic value of existing fortifications. In response, new defensive towers such as Tor San Michele and Tor Boacciana were constructed. The surrounding landscape remained marshy and malarial, limiting permanent settlement and economic development during this period.

Modern Period and 19th Century Land Reclamation (19th–early 20th century)

By the 19th century, the Ostia region was characterized by extensive salt pans and malaria-infested marshlands along the Tyrrhenian coast, with minimal permanent habitation. Following Rome’s annexation to the Kingdom of Italy in 1870, a comprehensive land reclamation (bonifica) project was initiated to drain the marshes and render the land suitable for agriculture and settlement. Beginning in the 1880s, cooperative laborers from Ravenna, led by figures such as Federico Bazzini and Armando Armuzzi, undertook hydraulic engineering works including the construction of canals and installation of pumping stations. Despite harsh environmental conditions and a high mortality rate from malaria, these efforts successfully drained over 1,500 hectares by 1889, transforming the landscape and enabling permanent habitation.

20th Century Urban Development and Cultural Evolution

The early 20th century witnessed the planning and development of Ostia Nuova as a seaside extension of Rome. Urban plans formalized by 1916 aimed to integrate the area into Rome’s metropolitan framework. Under the Fascist regime, the settlement was renamed Ostia a Mare and developed with infrastructure such as the Roma-Lido railway and the via del Mare highway, enhancing accessibility. Architectural styles ranged from rationalist to eclectic, with notable constructions including the stabilimento balneare “Roma” and various villas designed by prominent architects. Ostia emerged as a popular resort destination for Romans, featuring multiple bathing establishments. The area sustained damage during World War II from Allied bombings and Axis scorched earth tactics, including destruction of key infrastructure. Post-war expansion transformed Ostia into a residential and tourist district with new neighborhoods and cultural institutions. The site also gained cultural prominence through its association with the writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, who depicted Ostia’s social realities and was murdered there in 1975.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Early Roman Period and Foundation (7th–4th century BCE)

During its initial phase, Ostia functioned primarily as a military settlement established to secure Rome’s control over the Tiber’s mouth and adjacent salt pans. The population was predominantly composed of Roman soldiers and their families, organized under a military hierarchy. Archaeological evidence of the fortified castrum constructed from tufa blocks indicates a focus on defense and naval operations rather than civilian urban life. Daily activities centered on maintaining fortifications and overseeing river access. Dietary remains suggest consumption of staple foods such as bread, olives, and fish sourced from the nearby river and sea. Clothing likely conformed to Roman military standards, including tunics and cloaks. Religious practices probably combined early Roman cults with local traditions, potentially linked to Vulcan worship predating Roman settlement. Ostia’s civic role was that of a strategic military outpost rather than a municipium or commercial center.

Late Republican Period (2nd–1st century BCE)

By the late Republic, Ostia had evolved into a bustling commercial port serving Rome’s increasing demand for grain, salt, and other goods. The population diversified to include merchants, artisans, sailors, and freedmen alongside the military presence. Social stratification became more complex, with affluent traders and guild members residing in domus near the forum, while lower classes inhabited multi-storey apartment buildings (insulae). Epigraphic evidence attests to magistrates such as duumviri overseeing civic administration. Markets thrived near the forum and macellum, offering imported commodities including wine, olive oil, and luxury items. Transportation combined riverine vessels, coastal ships, and carts along the via Ostiense. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and painted walls, reflecting Roman decorative tastes. Religious life centered on traditional Roman deities, with temples and shrines within the city walls. Ostia’s importance lay in its role as Rome’s principal maritime gateway, facilitating trade and provisioning the capital.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–3rd century CE)

The Imperial era marked Ostia’s zenith as a populous and economically vibrant port city, with an estimated population of approximately 50,000 inhabitants. The demographic composition was ethnically diverse, including Roman citizens, freedmen, immigrants from across the empire, and slaves. Family structures ranged from elite households with private baths and atria to crowded insulae accommodating working-class families. Gender roles adhered to Roman norms, with men engaged in commerce, administration, and guild leadership, while women managed households and participated in religious cults. Economic activities expanded to large-scale warehousing, maritime trade, and artisanal production, supported by horrea and scholae. Dietary remains indicate consumption of bread, fish, olives, fruits, and imported delicacies. Clothing included tunics, stolas, and cloaks, adapted to social status. Urban homes were richly decorated with frescoes and mosaics. The city featured public baths, a theatre, markets, and temples such as the Capitolium, evidencing a complex civic life. Ostia’s religious landscape encompassed traditional Roman gods and the imperial cult, with festivals and public ceremonies. Transportation relied on extensive river and sea networks, enhanced by Claudius’s and Trajan’s harbor constructions. Ostia functioned as a vital imperial port and commercial hub, administered by local magistrates and overseen by imperial officials.

Late Imperial and Late Antique Period (3rd–6th century CE)

From the mid-3rd century CE, Ostia experienced demographic decline and economic contraction as Portus supplanted it as Rome’s primary port. The population decreased and became more localized, with Christian communities gaining prominence. Residential patterns shifted, with some insulae repurposed or abandoned. Christian basilicas such as Pianabella and the Church of St. Herculanus emerged, reflecting the city’s ecclesiastical role as a bishopric seat. Funerary practices diversified, including sarcophagi and columbaria, indicating varied social strata and religious beliefs. Daily diet remained Mediterranean but may have simplified due to economic constraints. Clothing styles incorporated Christian modesty norms alongside traditional Roman garments. Markets and workshops persisted but at reduced scale, focusing on sustaining local needs. Transportation declined as the Tiber’s harbor silted, limiting maritime access. Ostia’s civic structure transitioned from imperial administration to ecclesiastical governance, with bishops assuming leadership amid political instability. Repeated sackings by barbarian groups further disrupted urban life, accelerating abandonment.

Medieval Period (6th–15th century CE)

Following abandonment, Ostia’s population dispersed, and the site ceased to function as an urban center. Remaining inhabitants were sparse, often associated with agricultural or defensive activities around restored towers such as the Boacciana. The area’s marshy and malarial conditions hindered resettlement. Ruins were quarried extensively for building materials, erasing much of the original urban fabric. Religious life persisted in a limited form, with the Boacciana Tower serving ecclesiastical and papal functions. Economic activity was minimal, focused on small-scale agriculture and fishing. Transport relied on river navigation where possible, though the altered Tiber course reduced accessibility. Ostia’s civic role was negligible, overshadowed by nearby emerging centers and the Papal States’ defensive priorities.

Modern Period and 19th Century Land Reclamation (19th–early 20th century)

By the 19th century, Ostia’s environs were dominated by malaria-infested marshes and salt pans, with no significant permanent population. The bonifica project transformed the landscape, enabling agricultural settlement by cooperative laborers primarily from Ravenna. These workers established new social structures based on collective management and endured harsh living conditions. Daily life involved land drainage, canal maintenance, and farming activities. Housing was modest, reflecting a rural working-class community.

Remains

Architectural Features

The earliest extant structures at Ostia Antica include the military castrum dating to the late 4th century BCE. Constructed from large tufa blocks, this rectangular fortified camp featured defensive walls and corner towers designed to secure the Tiber River’s mouth and the Lazio coastline. The castrum’s remains provide tangible evidence of Ostia’s initial military function prior to urban expansion.

By the late 2nd century BCE, Ostia was enclosed by substantial defensive walls built using opus reticulatum masonry, characterized by diamond-shaped tufa stones set in concrete. These walls defined the city’s urban perimeter and incorporated three principal gates: Porta Romana, Porta Laurentina, and Porta Marina. Portions of these fortifications survive, delineating the city’s boundary during the Republican and early Imperial periods. The walls were maintained and repaired over subsequent centuries but gradually lost strategic importance as Ostia’s harbor declined.

During the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, Ostia’s urban fabric expanded to include multi-storey apartment blocks (insulae), public baths, markets, temples, and civic buildings. Construction techniques employed Roman concrete (opus caementicium) and brickwork, with vaulted rooms and hypocaust heating systems evident in bath complexes. The city’s layout followed a grid pattern, with main thoroughfares such as the via Ostiense connecting Ostia to Rome. As harbor silting reduced maritime activity, the city contracted, leading to partial abandonment by the 5th century CE.

Key Buildings and Structures

Military Castrum

The military castrum represents the oldest archaeological structure at Ostia, dating to the late 4th century BCE. Built of large tufa blocks, it formed a fortified rectangular enclosure with defensive walls and corner towers. The castrum contained barracks and military facilities intended to secure the river mouth and coastline. Its foundations and wall remnants remain visible, illustrating Ostia’s initial defensive role before urban development.

City Walls and Gates

Constructed in the late 2nd century BCE, the city walls enclosed Ostia’s commercial center. Built in opus reticulatum, the walls incorporated three main gates—Porta Romana, Porta Laurentina, and Porta Marina—that controlled access. Surviving sections of these walls and gates outline the city’s boundary during the Republican and early Imperial periods. The fortifications were maintained through subsequent centuries but declined in significance as Ostia’s harbor silted.

Tor Boacciana

Situated on the left bank of the Tiber River at its mouth, the Tor Boacciana was constructed in the 2nd century CE under Emperor Trajan, as indicated by brick stamps. The tower likely functioned as a lighthouse or guard post overseeing river access. It underwent restorations in the 12th and 15th centuries, including a complete rebuild by Pope Martin V in 1420. Serving as a papal customs post in the 16th century, the tower was later abandoned. Its masonry and structural remains are extant, reflecting its long-term use and adaptations.

River Docks and Archaeological and Natural Park of the Salt Pans

Located approximately 200 meters west of Ostia’s main gates along Via delle Saline, the river docks constitute the largest surviving section of Ostia’s river port, often referred to as the “Republican banks.” The docks include a left river bank constructed of tufa blocks extending over 100 meters in length and 15 meters in width. The eastern section connects to the mainland via orthogonal concrete walls surfaced with opus reticulatum masonry. Grooves and ducts in the walls suggest the use of temporary equipment such as ropes or lifting machines for ship handling. These docks were part of a salt production and storage complex linked to nearby salt pans. The archaeological remains are predominantly subterranean and lie within a protected natural park featuring diverse flora and fauna.

Seaside Villas of Procoio

Along modern Via di Pianabella, parallel to the ancient coastline, lie the remains of monumental Roman seaside villas dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. These villas were connected to Rome by major roads including Via Ostiensis and Via Laurentina. The complex includes a bath facility and an extensive villa with a large two-storey nymphaeum-cistern featuring a water fountain. The bath complex contains a heated spa building with a swimming pool (natatio), a frigidarium (cold room) with an apsidal pool accessed by steps, and a calidarium (hot room) with hypocaust heating evidenced by suspensurae (pillars raising the floor) and tubuli (terracotta tubes in walls). A 160-meter-long buttressed wall with pictorial decoration faces the sea, serving as a monumental façade.

Church of St. Herculanus

This small medieval church near the modern Ostia Antica cemetery was constructed partly over Roman funerary structures dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The church’s walls and apse incorporate reused Roman materials and display opus vittatum masonry typical of the 4th to 5th centuries CE. Beneath the church floor lies a large ossuary indicating continuous funerary use from Roman times through the Middle Ages. The church is dedicated to St. Herculanus, a Roman soldier martyred during the persecution under Emperor Claudius Gothicus. Commemorative plaques honor workers involved in 19th-century land reclamation. The surrounding enclosure serves as a burial site for notable archaeologists associated with Ostia’s excavation history.

Necropolis and Christian Basilica of Pianabella

The Pianabella Necropolis covers approximately 50 hectares near the modern cemetery, characterized by five parallel burial humps likely marking ancient cemetery paths. Used intensively from Roman times until the 4th century CE, it contains various burial types including sarcophagi, urns, columbaria (collective tombs with niches), fossae (pit graves), and cappuccina tombs (tile-roofed graves). An elaborately decorated sarcophagus featuring Centauromachy scenes from the early 2nd century CE is preserved in the Ostia Antica Museum. Between the 4th and 5th centuries CE, part of the necropolis was cleared to construct a Christian basilica comprising a single hall, apse, and porch. Inside, a funerary enclosure with hundreds of tombs arranged in parallel rows and levels was established. The basilica’s funerary function persisted until the 9th century CE.

Laurentina Necropolis

Excavated in 1804, the Laurentina Necropolis yielded painted tombs known as the Tombs of Claudii, discovered in 1865. These four tombs bear inscriptions commemorating freedmen of Emperor Claudius. The tomb paintings were removed and are now housed in the Vatican Museums. The necropolis provides valuable evidence of burial practices and funerary art from the Imperial period.

Imperial Harbours of Claudius and Trajan

Harbour of Claudius: Initiated in 42 CE by Emperor Claudius approximately three kilometers north of the Tiber mouth, this harbor was constructed to mitigate silting problems at Ostia’s riverbanks. The basin covered about 150 hectares and featured two curved piers, docks, and a multi-storey lighthouse situated on a small artificial island between the piers. Completed in 64 CE under Nero, the harbor facilitated the unloading of large cargo ships and the transfer of goods to smaller vessels navigating the Tiber. Foundations of the northern pier remain visible near the Fiumicino Roman Ships Museum. Associated structures include the harbour master’s office (Capitaneria), a cistern, and thermal baths known as the Monte Giulio complex, all dating to the 2nd century CE.

Harbour of Trajan: Constructed between 100 and 112 CE to address sediment accumulation in Claudius’ harbor, Trajan’s harbor reused existing piers and lighthouse as an external basin. It added a 33-hectare hexagonal basin, significantly increasing docking capacity. Canals such as the Fossa Traiana (now Fiumicino canal) were excavated to drain floodwaters. The harbor replaced Pozzuoli’s port and connected to Rome via the via Portuense. Key buildings on the northwest side include the Magazzini Severiani, a large warehouse complex, and the Palazzo Imperiale, a ceremonial palace. Additional warehouses, Magazzini Traianei, lined the Darsena inland basin with docks for smaller ships. In 314 CE, the harbor and village were declared the independent city Portus Romae with fortifications. Sediment accumulation and coastline changes eventually filled the basin, leading to decline.

Monte Giulio Complex and Capitaneria (Harbour Office)

Located near the Museo delle Navi (Fiumicino Roman Ships Museum), Monte Giulio is a small hill formed on an ancient port quay marking the northern limit of Claudius’ harbor basin. Excavations since 1968 uncovered a large water tank and small thermal baths visible along the modern road. The harbour offices (Capitaneria), dating to the 1st century CE and restored through the 4th century, were found nearby. One room contained a painted vault fresco discovered in the 1980s. Due to safety concerns, these structures are currently closed to the public.

Necropolis of Portus (Isola Sacra)

Located on the island formed by the Tiber delta and the Fossa Traiana canal, the Necropolis of Portus contains over 200 funerary structures dating from the late 1st to the 4th century CE. Tombs are arranged along Via Flavia, forming a continuous street front with facades decorated by brickwork, triangular gables, columns, and travertine-framed doors. Inscriptions in Latin and Greek provide names, testamentary details, and social information about the Portuenses, mostly middle-class merchants and freedmen. Bas-reliefs depict various professions. Tomb 78 bears an inscription naming T. Claudius Eutychus as owner.

Other Remains

Additional archaeological remains include the ancient via Severiana at Castel Fusano, a Roman domus on Via Ponte di Tor Boacciana, and an ancient Roman villa with a thermal zone in Pineta di Procoio. The area also contains fragments of Roman walls and remains of a coastal villa in Pineta di Procoio. These structures date primarily from the 1st to 4th centuries CE and contribute to understanding the broader settlement and landscape around Ostia.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Ostia Antica have yielded a wide array of artifacts spanning from the late Republican through Late Antique periods. Pottery assemblages include amphorae and tableware, both locally produced and imported, reflecting extensive trade networks. Numerous inscriptions, including dedicatory and funerary texts, provide insights into social status, professions, and civic organization. Coins from multiple emperors and dynasties assist in stratigraphic dating. Tools related to agriculture and crafts have been recovered from workshops and domestic contexts. Domestic objects such as oil lamps and cooking vessels illustrate aspects of daily life. Religious artifacts, including statuettes and altars, have been found in temples and shrines within the city.

Preservation and Current Status

Many of Ostia Antica’s structures are well-preserved, including sections of the city walls, gates, insulae, and public buildings. The military castrum’s foundations and the Tor Boacciana tower remain visible, though some are fragmentary. The river docks and salt pans area is largely subterranean but protected within a natural park. The seaside villas retain substantial architectural elements such as walls, cisterns, and bath complexes. Restoration efforts have stabilized key structures, with some reconstructions employing modern materials for conservation. The Church of St. Herculanus and the Pianabella basilica have been conserved, with the latter reburied after excavation to protect remains. Environmental threats such as erosion and vegetation growth are managed by heritage authorities. Excavations continue selectively, with safety considerations limiting access to certain sites like the Monte Giulio complex.

Unexcavated Areas

Several districts within Ostia Antica remain partially or wholly unexcavated. Surface surveys and geophysical studies indicate buried remains beneath modern soil and vegetation cover. Some areas are restricted due to conservation policies or modern land use. Future excavations are planned selectively, balancing archaeological research with preservation concerns. While no major urban sectors remain entirely unexplored, smaller structures and peripheral zones await further investigation.