Olympos Ancient City: A Lycian Coastal Settlement in Turkey

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: muze.gov.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Olympos Ancient City is located on the Lycian coast within Antalya Province, near the modern town of Kumluca in southwestern Turkey. The site occupies a coastal valley that opens onto a beach at the mouth of a small river, known today as the Akçay or Olympos Çayı. It lies beneath the steep slopes of the Beydağları mountain range, where rugged terrain descends sharply to the Mediterranean Sea.

The surrounding landscape combines maritime and mountainous environments, providing access to natural resources such as timber, fertile soils, and marine products. The site’s position along the Lycian coast placed it within a network of cities connected by land and sea routes, including the ancient Lycian Way trade path. Archaeological evidence demonstrates continuous occupation from the Lycian period through Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine times, reflecting the city’s adaptation to shifting political and economic circumstances.

Surface remains include rock-cut tombs, inscriptions, and architectural fragments scattered across the valley and adjacent pine forests. Subsurface deposits contain buried structures and evidence of coastal sedimentation that gradually obscured the ancient harbor. The site has been documented since the nineteenth century and has undergone systematic archaeological survey and excavation in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Olympos is protected as a cultural heritage site, with ongoing conservation efforts addressing natural and human-induced threats.

History

Olympos Ancient City’s historical trajectory illustrates the complex interplay between indigenous Lycian traditions and successive external influences, shaped by its strategic coastal location. The city’s development spans from its Lycian origins through Hellenistic autonomy, Roman imperial integration, Christianization in late antiquity, and eventual decline during the medieval period. Its history is marked by episodes of political autonomy, pirate control, imperial patronage, and ecclesiastical significance, reflecting broader regional transformations in Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean.

Lycian and Hellenistic Period (1st millennium BCE – 2nd century BCE)

Archaeological and epigraphic evidence confirms that Olympos was established by the late 4th century BCE, during the Hellenistic period or earlier. The city’s name derives from the nearby Mount Olympus (present-day Tahtalı Dağı or Musa Dağı), a prominent geographic landmark. Olympos was a significant member of the Lycian League, a federation of city-states in the region, holding three votes by the late 2nd century BCE. This voting weight placed it among the six largest and most influential Lycian cities.

During this period, Olympos minted coinage on behalf of the Lycian League, beginning possibly in the 130s BCE, indicating its active participation in regional economic and political affairs. The city was fortified with defensive walls, and inscriptions attest to local magistrates and civic officials, demonstrating an organized municipal administration. Its coastal position facilitated maritime trade and communication with neighboring Lycian cities and the wider Mediterranean world, while religious practices combined indigenous Lycian cults with Hellenistic influences.

Late Hellenistic Period and Pirate Rule (circa 100 BCE)

In the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BCE, Olympos experienced a period of political upheaval linked to the rise of Cilician piracy in the eastern Mediterranean. Around 100 BCE, the city came under the control of the pirate leader Zeniketes, who established autonomous rule over Olympos and its maritime possessions, including the nearby harbors of Corycus and Phaselis in Pamphylia. During this time, Olympos issued its own coinage independent of the Lycian League, reflecting a break from previous political affiliations.

Zeniketes’s dominion ended in 78 BCE following a Roman naval campaign led by Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus, with the young Julius Caesar participating in the operation. The defeat culminated in Zeniketes setting fire to his residence in Olympos and perishing with his family, effectively terminating pirate control. This episode illustrates the city’s strategic maritime importance and its entanglement in wider conflicts between local powers and Roman expansion.

Roman Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following its incorporation into the Roman Republic and later the Empire, Olympos underwent significant urban and administrative changes. Cicero described the city as wealthy and richly adorned, reflecting its prosperity under Roman rule. Emperor Hadrian’s visit around 130 CE led to the city’s renaming as Hadrianopolis, signifying its integration into the imperial system and imperial favor. The original mountain settlement was likely destroyed during Roman consolidation, prompting a population shift to the coastal harbor area of Corycus, which was renamed Olympos in honor of the emperor.

The city maintained religious traditions, notably the cult of Hephaistos, associated with the nearby eternal flames of Chimaira (Yanartaş), a natural gas seep that produced continuous fires on the hillside. Olympos experienced significant seismic events in 141 and 240 CE, which affected its urban fabric and development. Inscriptions from the 2nd century CE mention Marcus Aurelius Arkhepolis as Lykiarch, the president of the Lycian League, indicating the city’s ongoing political prominence within the provincial framework. Notably, Olympos was absent from major Roman maritime itineraries before the 2nd century CE, suggesting its emergence as a harbor city was a later development.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (3rd century CE – 8th century CE)

By the 3rd century CE, Olympos had become a Christian bishopric subordinate to the metropolitan see of Myra, the capital of Roman Lycia. The earliest recorded bishop, Saint Methodius of Olympus, served until his martyrdom around 311 CE. Subsequent bishops, including Aristocritus, Anatolius, and Ioannes, participated in significant ecclesiastical councils and synods during the 5th and 6th centuries, reflecting the city’s religious role within the Byzantine church hierarchy.

Despite recurring earthquakes, notably in 542 CE, the city sustained urban life into the early medieval period. Archaeological evidence reveals that from the 4th century CE, affluent residents constructed large houses with spacious courtyards near the northern necropolis, sometimes reusing materials from earlier tombs. The Entrance Complex, dating to the 5th and 6th centuries CE, comprised multiple rooms arranged over two floors with arcaded facades, serving residential, food production, and commercial functions. A temple dating to circa 175 BCE, featuring a monumental gate adorned with acanthus motifs and a statue honoring Emperor Marcus Aurelius, attests to continued religious and cultural activity during the Roman Imperial era.

Medieval Period and Decline (11th century – 15th century)

During the Crusades, Olympos came under the control of Venetian, Genoese, and Rhodian forces, who constructed and expanded fortifications to secure the city’s strategic coastal position. A Genoese castle on the eastern shore and defensive use of the acropolis exemplify the militarization of the site in this period. The mid-14th century brought devastating plague epidemics in 1346 and 1347, which reduced the population by approximately half, severely impacting the city’s social and economic structures.

Following the Ottoman conquest in the 15th century, Olympos was abandoned as a permanent settlement. The decline reflects broader regional shifts in trade routes, political control, and demographic patterns that led to the cessation of urban life at the site.

Post-Medieval and Modern Period (18th century – present)

After abandonment, the ruins of Olympos served as seasonal winter quarters for nomadic Yörük groups during the 18th and 19th centuries. The site remained largely forgotten until British naval officer Francis Beaufort documented its geography and ruins during his 1811–1812 expedition, publishing his observations in 1817. Around 1850, a local resident constructed a water mill on the southern harbor road using stones salvaged from the ancient structures.

The absence of modern urban development contributed to the preservation of many ancient architectural elements, including a bridge connecting the city’s two halves across the Akçay River. In recent decades, the site has faced natural hazards such as fires and floods but remains under heritage protection. Ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts aim to safeguard Olympos’s multifaceted historical legacy.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Lycian and Hellenistic Period (1st millennium BCE – 2nd century BCE)

During the Lycian and Hellenistic periods, Olympos functioned as a significant urban center within the Lycian League, with a population primarily composed of indigenous Lycians influenced by Hellenistic culture. The social structure included local elites who participated in league governance, alongside artisans, merchants, and laborers. Inscriptions document civic magistrates responsible for municipal administration, indicating organized political institutions.

Economic activities centered on agriculture, maritime trade, and coin minting, with the city producing its own currency from the late 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE. Archaeological evidence suggests households combined farming with craft production. The coastal location facilitated commerce through a harbor, connecting Olympos to regional and Mediterranean trade networks. Religious life integrated Lycian mountain cults and Hellenistic deities, consistent with the city’s name and geographic setting.

Late Hellenistic Period and Pirate Rule (circa 100 BCE)

The period of pirate control under Zeniketes brought significant changes to Olympos’s social and economic organization. The population likely comprised local inhabitants and pirate factions, with governance shifting toward militarized authority. The issuance of independent coinage reflects a declaration of autonomy from the Lycian League.

Economic life was dominated by piracy, with maritime raids and control over coastal trade routes shaping activities. The city’s harbor and possessions such as Corycus and Phaselis served as pirate bases, disrupting traditional commerce. Residential areas may have become more fortified, although archaeological evidence is limited. Religious practices likely continued but under conditions of political instability. The Roman naval campaign that ended pirate rule resulted in the destruction of Zeniketes’s residence and a violent reordering of the city’s social structure.

Roman Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Under Roman rule, Olympos underwent urban reorganization and economic expansion. The population included Roman settlers alongside indigenous Lycians, with a social hierarchy comprising local elites, Roman officials, merchants, artisans, and laborers. Inscriptions mention civic leaders such as Marcus Aurelius Arkhepolis, indicating the city’s political role within the Lycian League under Roman administration.

The city’s relocation from the mountain site to the harbor area of Corycus, renamed Olympos, facilitated maritime trade, fishing, and shipbuilding. The cult of Hephaistos, linked to the nearby eternal flames of Chimaira, remained a religious focal point. Domestic architecture featured mosaic floors and painted walls, reflecting Roman aesthetic preferences. Public infrastructure included a bridge connecting city sectors and a small theater, supporting civic and social activities. The city’s renaming as Hadrianopolis after Emperor Hadrian’s visit symbolized its elevated status within the empire.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (3rd century CE – 8th century CE)

In late antiquity, Olympos became a Christian bishopric, marking a shift in religious and social life. The population maintained a blend of Lycian and Roman identities, with ecclesiastical leaders such as Saint Methodius and his successors playing prominent roles. Social stratification included wealthy landowners who built large courtyard houses near the northern necropolis, sometimes reusing tomb materials, alongside common residents.

Economic activities diversified, as evidenced by the Entrance Complex, which combined residential, food production, and trade functions at a household or workshop scale. Domestic architecture featured arcaded facades and multi-room layouts, adapting to late antique lifestyles. Christian worship took place in basilicas, while pagan cults declined. Despite recurring earthquakes, Olympos sustained urban life through the 6th century within the Byzantine provincial system.

Medieval Period and Decline (11th century – 15th century)

During the medieval period, Olympos’s population declined and became militarized under Crusader and maritime powers such as the Venetians, Genoese, and Rhodians. The social structure centered on military and mercantile elites controlling fortifications, including a Genoese castle, while the remaining populace engaged in subsistence activities and local trade. The plague epidemics of the mid-14th century severely reduced inhabitants, disrupting social and economic life.

Economic activities contracted, focusing on defense and limited commerce linked to Crusader maritime routes. Urban spaces were adapted for fortification rather than civic or commercial use. Religious life remained Christian, with ecclesiastical structures maintained but overshadowed by military concerns. The city’s regional role diminished, and the Ottoman conquest led to abandonment, ending continuous habitation.

Post-Medieval and Modern Period (18th century – present)

Following abandonment, the ruins of Olympos served as seasonal winter quarters for nomadic Yörük groups, marking a transition from urban settlement to pastoral use. The population was transient and sparse, with no permanent civic or economic structures. Architectural remains, including a bridge and salvaged stones, reflect reuse rather than new construction.

Economic life was minimal, limited to pastoralism and small-scale agriculture. Transport relied on traditional animal caravans and footpaths, with no formal markets or trade centers. Religious practices reflected those of the nomadic groups, distinct from ancient Christian and pagan traditions. The site’s significance shifted to archaeological and cultural heritage, with early 19th-century documentation initiating scholarly interest and modern conservation efforts preserving its historical legacy.

Remains

Architectural Features

Olympos Ancient City extends on both sides of the Akçay River, which divides the site into two sectors connected by the remains of an ancient bridge. The riverbed is heavily silted, with minimal flow during summer and increased volume in winter. The urban layout encompasses a coastal valley and beach area, with ruins spreading into adjacent pine forests. Construction predominantly employed local limestone, with unplastered masonry characteristic of Lycian architecture. The site exhibits multiple occupation phases from Lycian through Byzantine periods, including residential, religious, and defensive structures.

Key Buildings and Structures

Bridge over Akçay River

The bridge spanning the Akçay River linked the mountain settlement with the harbor area, facilitating movement within the city. Although partially preserved, the structure’s remains are visible despite riverbed sedimentation. The bridge’s construction date is uncertain but corresponds to Roman and Byzantine occupation phases, reflecting the city’s spatial organization and infrastructure.

Deliktaş (Perforated Rock)

Deliktaş is a natural rock formation near the beach featuring a roughly two-meter-high passage that historically served as the sole road into the adjacent valley. Above the passage, embedded fragments of roof tiles indicate the former presence of an overhead covering, possibly a constructed gateway or shelter. Due to sediment accumulation, the passage now lies approximately 20 meters inland from the current shoreline, though winter storms occasionally bring the sea close to the rock.

Entrance Complex

Situated on the northern side of the city behind the open-air museum entrance, the Entrance Complex dates to the 5th and 6th centuries CE. It comprises eleven ground-floor rooms with evidence of an additional upper floor containing a similar number of rooms. Two arcaded walkways run along the north and south sides, each accessible through five round arches. The southern corridor likely functioned as an observation point overlooking the river. Architectural and artifact evidence indicates the building served residential, food production, and commercial purposes. Its irregular expansions suggest organic growth rather than a preplanned design, reflecting daily life in late antiquity.

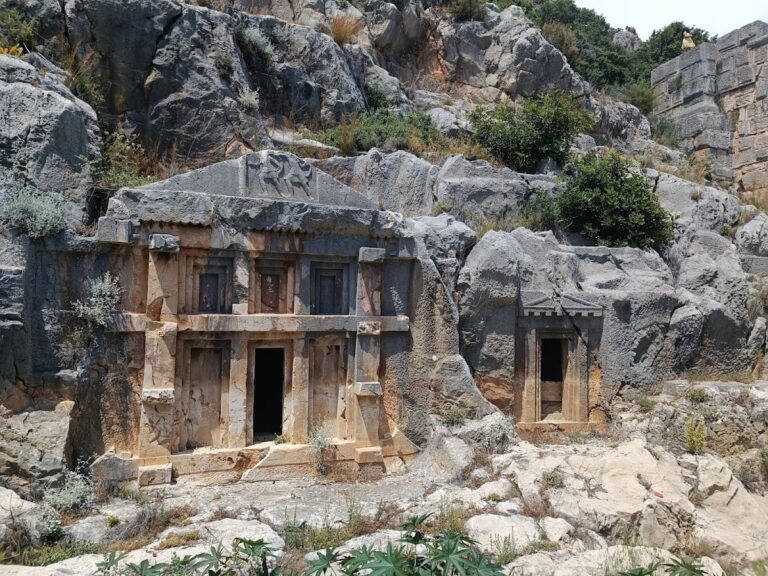

Temple (Northern City Area)

Located in the northern sector, this temple was identified by early scholars George Bean and Cevdet Bayburtoğlu. Constructed circa 175 BCE, it features a monumental gate standing 4.88 meters high. The lintel is decorated with acanthus motifs and an unfinished row of bead designs. The masonry is unplastered, consistent with Lycian architectural traditions. A statue fragment bearing an inscription dedicates the temple to Emperor Marcus Aurelius, indicating continued religious use into the Roman Imperial period. The temple’s precise deity dedication remains uncertain, though its association with imperial cult practices is evident.

Northern Necropolis

The northern necropolis contains 113 individual tombs, none interconnected, dating from the 1st to mid-3rd centuries CE. From the 4th century CE onward, large residential buildings with spacious courtyards were constructed along the road traversing the necropolis. Some houses were built adjacent to tombs, incorporating materials reused from earlier funerary monuments. The necropolis acquired its present form in the 5th century CE, reflecting continued urban development and habitation during late antiquity.

Alkestis Sarcophagus (Southern Necropolis)

This richly decorated limestone sarcophagus, dated between 180 and 200 CE, belonged to Aurelius Artemias and his family. The lid imitates a house roof and attic. Reliefs depict mythological figures such as Eros, Nike, and Medusa’s head. A Tabula Ansata bears Greek inscriptions naming the sarcophagus owners. The sarcophagus features a “Dextrarum Iunctio” (handshake) scene symbolizing marriage. On the short side, carvings include a female figure wearing chiton and himation, the healing and oracle god Heracles, and a winged male figure, illustrating a blend of Roman and local iconography.

Byzantine Basilica

Remains of a Byzantine basilica are located on a hill within the site. The structure dates to the Byzantine period and reflects the settlement’s decline during the Middle Ages. Architectural fragments include elements typical of basilicas, such as a nave and aisles, though preservation is fragmentary. The basilica attests to the city’s Christian ecclesiastical presence in late antiquity and the medieval era.

Genoese Fortress (Eastern Shore)

Constructed and expanded by Venetian, Genoese, and Rhodian forces during the 11th and 12th centuries, the Genoese fortress occupies the city’s eastern shore. It incorporates the acropolis and served defensive functions during the Crusades. Substantial sections of walls and towers remain visible, illustrating the militarization of the site in the medieval period.

Other Archaeological Features

The site includes a small Roman theater, now heavily overgrown and in a state of decay. A temple ruin dating to the 2nd century CE lies within a former lake area, currently marshy. Numerous graves and inscriptions are found in the necropolises, though they lack typical Lycian stylistic features. Excavations conducted between 2000 and 2006 uncovered sarcophagi with significant damage. Surface traces of the former lake area and associated temple ruins remain visible. Residential buildings near the northern necropolis include some constructed with reused tomb materials, reflecting adaptive reuse practices.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded a diverse assemblage of artifacts spanning Lycian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods. Inscriptions include Lycian texts and Greek dedications, such as those on the Alkestis Sarcophagus and the temple statue fragment. Coinage from the Lycian League and independent pirate issues has been documented. Funerary reliefs and sarcophagi display Roman artistic motifs. Pottery fragments, including amphorae and tableware, have been recovered from domestic and trade contexts. Tools and household objects such as lamps and cooking vessels provide insight into daily activities. Religious artifacts linked to the cult of Hephaistos and the Christian bishopric have been identified through inscriptions and architectural remains.

Preservation and Current Status

Many ruins at Olympos remain visible, though some structures are fragmentary or heavily overgrown. The bridge over the Akçay River survives in part, while the Roman theater is in poor condition. The Entrance Complex and temple gate are relatively well-preserved. The Genoese fortress retains substantial wall sections. The site has faced natural threats including sedimentation, fires, and floods. Conservation efforts are ongoing, with heritage protection measures in place. Excavations primarily conducted between 2000 and 2006 have documented and stabilized key structures. Some areas are stabilized but not fully restored, preserving original materials in situ.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of Olympos remain unexcavated or insufficiently studied. Surface surveys and geophysical investigations suggest buried architectural remains beneath sand and alluvial deposits, particularly in the coastal plain and former harbor zone. The former lake area with temple ruins is only partially explored. Future excavations depend on conservation policies and environmental conditions. No modern developments currently obstruct potential archaeological work, though sedimentation and vegetation growth present challenges to site investigation.