Motya: An Ancient Phoenician City in Sicily

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: www.fondazionewhitaker.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Greek, Phoenician, Roman

Site type: City

History

Motya, also known as Mothia or Mozia, was an ancient Phoenician city located on San Pantaleo Island in the Stagnone Lagoon near Marsala, in the province of Trapani, western Sicily, Italy. Founded around the 8th century BC, it began as a commercial trading post established by Phoenician settlers. Its position on a small island provided natural protection and allowed it to develop into a wealthy and strategically important city.

During its early history, Motya became one of the main Phoenician settlements in western Sicily, alongside Solunto and Palermo. It served as a key stronghold for Phoenician and later Carthaginian power in the region. Ancient historians such as Thucydides and Diodorus Siculus mention Motya, highlighting its significance in Mediterranean affairs. The city was closely linked to the worship of deities like Baal and Astarte, reflecting its religious and cultural ties to Phoenician traditions.

In 397 BC, Motya faced a major military event when Dionysius I of Syracuse laid siege to the city. After a prolonged resistance, the Syracusan forces breached the fortifications. The population was massacred, and the city was briefly occupied by Dionysius. However, in 396 BC, the Carthaginian general Himilcon recaptured Motya, restoring it under Carthaginian control. Despite this recovery, Motya’s importance declined as the nearby city of Lilybaeum (modern Marsala) rose in prominence.

Following this period, Motya experienced a gradual decline. During the Roman era, the site saw limited occupation, mainly evidenced by scattered villas rather than urban development. In the 11th century AD, Basilian monks renamed the island San Pantaleo, marking a shift in its cultural and religious identity. In the early 20th century, Joseph Whitaker acquired the island and began systematic archaeological excavations, uncovering much of Motya’s ancient heritage.

Remains

Motya was built on a small island roughly 850 meters long and 750 meters wide. It was connected to the Sicilian mainland by an artificial causeway about 1.7 kilometers long and 7 meters wide, constructed in the mid-6th century BC to allow chariot passage. The city was enclosed by a massive fortification circuit approximately 2.5 kilometers in length, featuring rectangular and square towers spaced about 20 to 23 meters apart. The walls, up to 5 meters thick in their final phase, were built using limestone blocks with mudbrick superstructures.

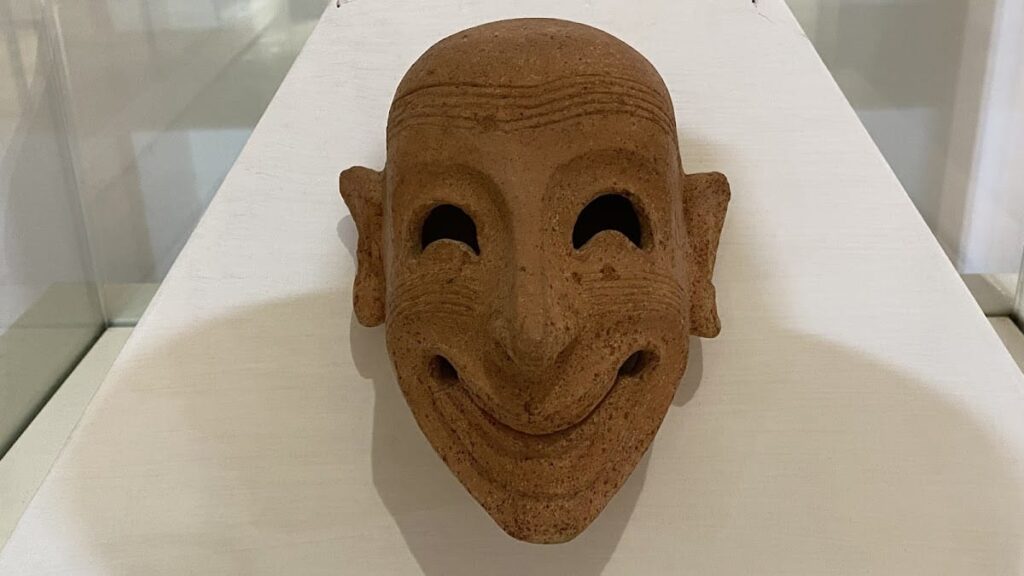

The North Gate complex included three successive double-arched gates spaced roughly 22 meters apart. Nearby were small sanctuaries dating from the 6th and 5th centuries BC. Decorative elements found here include a sculptural group of two felines attacking a bull, capitals in Doric and proto-eastern styles, and reliefs depicting battle scenes. These features highlight the city’s religious and defensive character.

Motya’s urban layout combined an orthogonal street grid in the central area with streets paved in large limestone slabs and equipped with drainage systems. Peripheral neighborhoods followed the coastline’s orientation. The city’s water management system included wells, cisterns, drainage channels, and rainwater collection integrated into buildings and streets.

A notable feature is the Kothon, a rectangular artificial basin measuring about 52.5 by 35.7 meters and up to 2.5 meters deep. Originally a freshwater sacred pool linked to a temple complex dedicated to the god Baal, it was enclosed by carved limestone blocks and fed by a natural spring. In Roman times, the Kothon was converted into a fishpond and saltworks.

Adjacent to the Kothon were three temples, including those dedicated to Baal and Astarte, dating to the earliest Phoenician settlement phase around 800 to 750 BC. The Cappiddazzu sanctuary near the North Gate underwent several construction phases from the early 7th century BC to the 4th century BC. It culminated in a large tripartite building within a 27.4 by 35.4 meter enclosure, containing altars, sacred stones called betyls, a large cistern, and evidence of sacrificial rituals.

The southern part of the island housed the “House of Mosaics,” a two-level residential complex built against the city walls. It featured a peristyle courtyard paved with pebble mosaics depicting animals such as lions, bulls, griffins, and deer. These mosaics date to the 3rd century BC. The house also contained service rooms with large storage jars called pithoi and showed reuse of architectural elements from earlier buildings.

The “Casermetta” was a building attached to a large tower on the southern walls. Divided into two parts flanking an open corridor with a staircase to an upper floor, its walls were constructed using a “frame” technique with large sandstone blocks and smaller stones as infill. This building was destroyed by fire, likely during the 397 BC siege.

Motya’s necropolis lay along the northern coast and featured cremation burials in rock-cut graves. Cinerary urns of various types, including tuff slabs, amphorae, and monolithic stone boxes, were found. Grave goods included Phoenician-Punic and imported Greek ceramics, weapons, and jewelry, mainly dating from the late 8th to 7th centuries BC.

The tofet, a sacred burial ground for cremated children, extended about 60 meters along the northern coast between the sea and city walls. It was in use from the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC. Archaeologists uncovered multiple layers of urns, stelae with inscriptions and symbolic reliefs, and small temples, including a rectangular temple built in the mid-6th century BC.

Industrial areas were located along the northern and eastern coasts. These included ceramic workshops with bipartite buildings, kilns, large storage jars, and facilities for metalworking and dyeing, notably producing purple dye from sea snails called murices. These industrial zones were destroyed during the 397 BC siege and covered by debris.

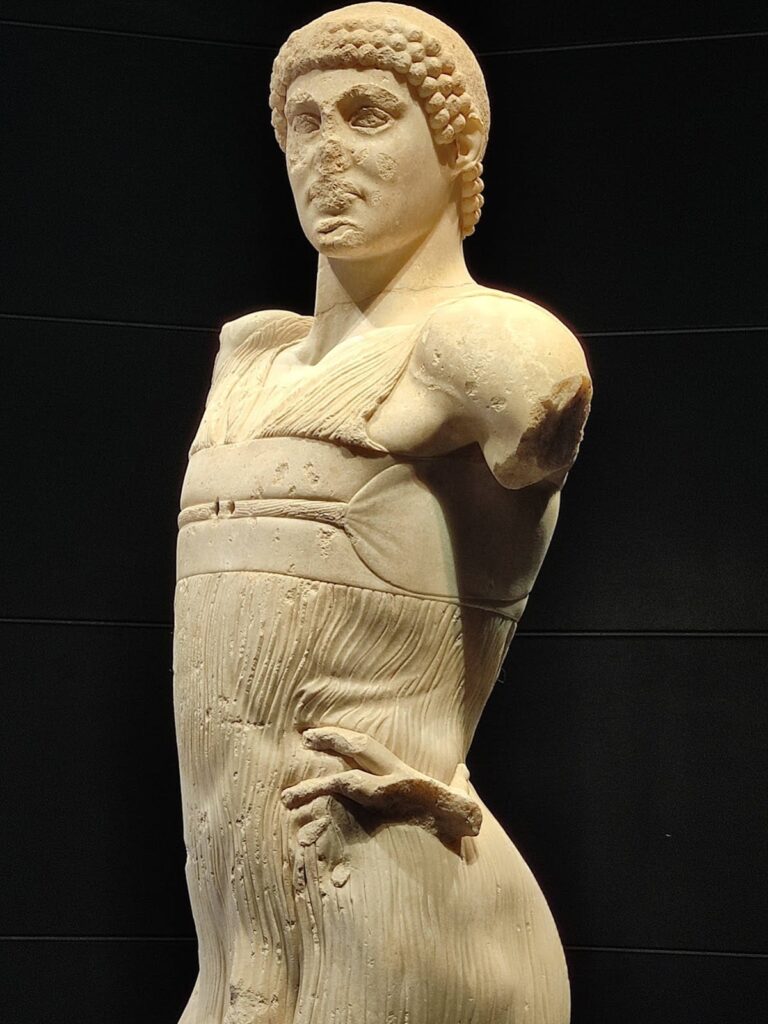

Numerous inscriptions, votive offerings, and sculptural finds attest to Motya’s religious and cultural life. Statues of deities such as Astarte were found within the western fortress sector. The site preserves visible remains of walls, gates, temples, houses, and industrial installations. Artifacts from Motya are housed in the Giuseppe Whitaker Museum on the island.