Julióbriga: An Ancient Roman Settlement in Cantabria, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: centros.culturadecantabria.com

Country: Spain

Civilization: Roman

Remains: City

History

Julióbriga is an ancient Roman settlement located in the municipality of Retortillo in Spain. Built by Roman forces, it became the most important urban center among several founded in the Cantabria region during the early Imperial period.

The city’s foundation occurred between 15 and 13 BCE, shortly after the Cantabrian Wars concluded. It was established by the Legio IV Macedonica, a Roman legion active during this time. Julióbriga likely grew on the site of a prior Cantabrian fortification, reflecting a common Roman practice of building over local settlements to exert control. Its name honors Gaius Julius Caesar, who was the adoptive father of Emperor Augustus, under whose leadership the city was created. Julióbriga acted as a civil hub, administering not only the Besaya river valley but also surrounding territories including an uncertain stretch of nearby coastline. The city had maritime access through the Portus Victoriae Iuliobrigensium, a port probably corresponding to the modern area of Santander, itself founded in 26 BCE.

During the early years of settlement, the Romans maintained a military presence in the region to ensure stability. A semi-permanent camp was located nearby at Pisoraca, present-day Herrera de Pisuerga, holding troops until around 40 CE. As peace was established, Julióbriga’s urban planning was completed in the 1st century CE. The city grew further during the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69–79 CE), indicated by archaeological signs of expansion. Citizens from Julióbriga held notable civil positions in the provincial administration of Tarraconense during the later 1st and 2nd centuries CE, showing its importance within the broader Roman governance of northern Spain.

Julióbriga was connected by a Roman road network to other key sites, including Pisoraca and the coastal ports of Portus Blendium (modern Suances) and Portus Victoriae Iuliobrigensium. This route facilitated communication and trade between the northern coast and the interior Meseta plateau. Economic activities involved cereal farming and cattle raising, supported by the partly forested landscape of antiquity.

In the 3rd century CE, the city was abandoned as a major inhabited center. However, fragments of activity persisted into the 4th century, including small groups reoccupying parts of the site and evidence of minor fire damage. From the 5th century onward, the former urban area was repurposed as a cemetery, marking a significant shift in use. A Romanesque church, dedicated to Santa María de Retortillo, was erected over the old forum during the 12th century. Around it, a small village developed, reflecting continued settlement on the historic location. In 1057, the lands of Julióbriga were granted to the abbey of Santa Juliana, indicating integration into medieval ecclesiastical property.

Historical references to Julióbriga appear in several ancient texts. The naturalist Pliny the Elder mentioned the city around 60 CE, while the geographer Ptolemy included it in his 2nd-century works. Later, 5th-century administrative documents and inscriptions also record its existence, confirming its continued recognition through time. Excavations initiated in the mid-20th century have uncovered a selection of remains and artifacts spanning from the Iron Age through the Middle Ages, although modern developments have limited extensive investigation.

Remains

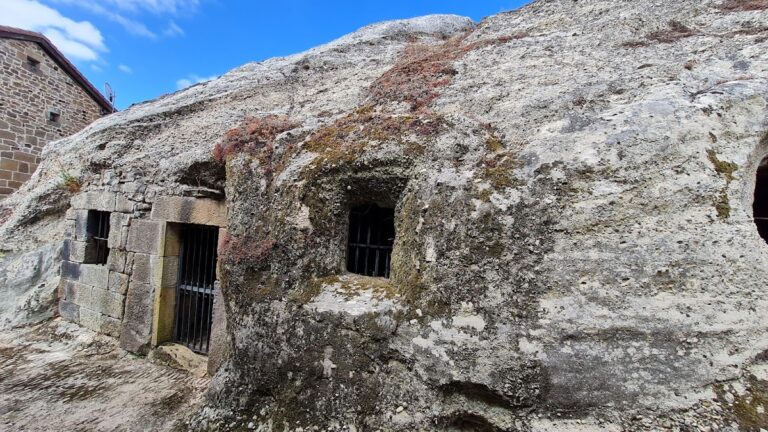

Julióbriga’s archaeological remains reveal an urban center arranged according to Roman planning principles and constructed using a combination of stone and earth materials. The most enduring structures are large masonry foundations made of sandstone blocks fitted with clay mortar. These robust bases supported walls built from adobes (sun-dried bricks), rammed earth (tapial), and wooden frameworks. Roofs featured wooden beams covered by tiles, while wealthier homes included decorative plaster and stucco finishes that would have brightened interior spaces.

One key feature at the site is a porticoed street characterized by square stone pilasters lining the area behind the central forum. This street would have served both as a commercial and social space in the city. The forum itself, a small rectangular space atop the site’s hill, served as the civic and administrative heart of Julióbriga. Its remains lie beneath the later Romanesque church of Santa María de Retortillo, which was constructed directly over it during the medieval period.

Several notable domestic buildings have been identified. The Casa de los Morillos, dated to around 80 CE, exemplifies early Imperial residential architecture. Another prominent residence, known as the Casa de los Mosaicos, is remarkable for its elaborate black and white mosaic floors, along with bath facilities heated by a hypocaust system—an underfloor heating method typical in Roman homes. These features indicate a high standard of living for its occupants.

The housing in Julióbriga included larger mansions with inner courtyards called peristyles, a common Roman design allowing for open private gardens or patios. Alongside these were blocks of more modest homes which lacked enclosed courtyards but utilized spaces around the buildings for secondary structures such as granaries, stables, and animal pens. These utilitarian buildings often rested on preserved supports and reflect an early form of local rural architecture, which later evolved into what is known as the Cantabrian Casa Montañesa style.

The city’s commercial quarter consisted of tabernae, or shop buildings, arranged in terraces adapted to the hillside terrain. These structures resembled insulae, the Roman equivalent of apartment blocks, and housed shops, warehouses, and possibly small workshops.

In 2003, the Domus Romana museum was opened at the site to display local artifacts, which had previously been kept in the Archaeological Museum of Santander. Among the objects recovered are a distinctive Roman omega-shaped fibula (a type of brooch) and an Augustan silver coin known as a denarius, both confirming the Roman origins and usage of the city.

Today, only the stone foundations and sections of masonry dating to the late 1st century CE remain visible. Timber and earth walls have largely disappeared over time, though their traces have been confirmed by excavations. Later medieval use of the site as a cemetery and the presence of the Romanesque church add complex layers to the archaeological record. The ruins that survive provide important insights into the city’s urban layout, domestic life, and its transition from a Roman provincial town to a medieval village center.