Halicarnassus: An Ancient Carian City and Mausoleum Site in Turkey

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Achaemenid, Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

Halicarnassus ancient city is located in Eskiçeşme, Bodrum, in modern-day Turkey. It was built by the Carian people and later became an important satrapal center under the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

The city gained prominence during the 4th century BC under the Hekatomnid dynasty, a line of Carian rulers who governed the region on behalf of Persia. Among them, Mausolus and his sister-wife Artemisia II were especially notable for their patronage of the city’s cultural and architectural development. After Mausolus’s death around 353 BC, Artemisia commissioned the construction of an elaborate tomb for Mausolus, which came to be known as the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. This tomb was finished around 350 BC and became one of the wonders of the ancient world.

Throughout its history, Halicarnassus maintained strong ties to the Persian Empire, as evidenced by artifacts such as a calcite jar inscribed in four languages with the seal of Xerxes I, which was found at the mausoleum site. Despite Persian domination, Mausolus displayed a deep admiration for Greek culture and its political ideals, reflected in the artistic style and decorative motifs of the city’s buildings.

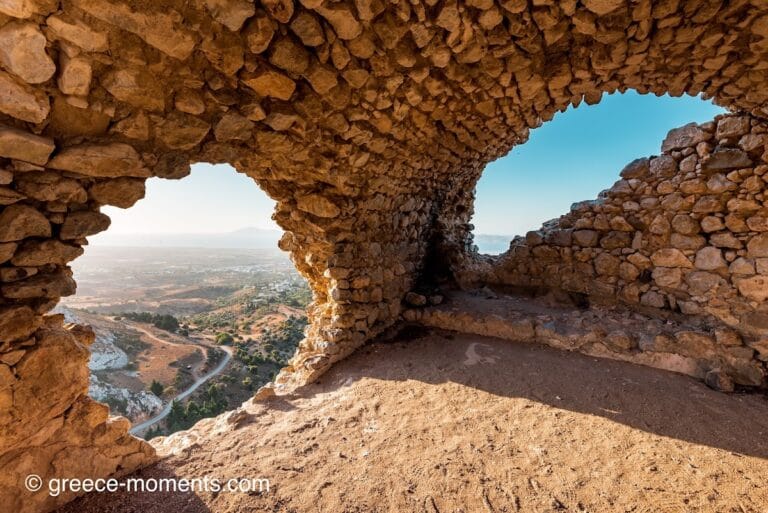

During the medieval period, the mausoleum was gradually damaged by a series of earthquakes from the 12th to the 15th centuries. By 1404, only the foundational base of the mausoleum remained clearly visible. Later in the 15th century, the Knights of St John of Jerusalem controlled the region and dismantled much of the mausoleum’s stonework to reinforce the nearby Bodrum Castle, repurposing sculptures and marble blocks for their fortifications. The burial chamber of Mausolus and Artemisia had been looted prior to this reuse, and it is believed that both were cremated, with urns placed inside the tomb rather than full bodies.

Archaeological interest in Halicarnassus resumed in the 19th century when British archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton conducted extensive excavations between 1852 and 1857. His work uncovered foundations, statues, and sculptural fragments associated with the mausoleum. Further detailed excavations between 1966 and 1977 by Kristian Jeppesen expanded understanding of the monument’s layout and artistry. These investigations have greatly contributed to reconstructing the site’s historical narrative.

Remains

The principal surviving features at Halicarnassus are those related to the renowned Mausoleum, originally a monumental tomb approximately 45 meters high. The structure was built on a raised hill overlooking the city to emphasize its significance. The base of the building was rectangular, spanning roughly 19 meters from north to south, enclosing an area with a perimeter near 125 meters. Excavations have revealed that its foundation reaches depths between 2.4 and 2.7 meters, covering about 33 by 39 meters of ground.

The mausoleum rested on a square podium, whose outer walls were adorned with elaborate sculpted reliefs depicting famous mythical battles such as those between the Amazons and Greeks, and between centaurs and Lapiths. These artistic panels were the work of four celebrated Greek sculptors—Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas, and Timotheus—each responsible for decorating one side of the podium. Adding further detail, life-sized stone warriors on horseback guarded each corner, and around twenty lion statues measuring about 1.5 to 1.6 meters long embellished the platform and stairways. This courtyard was enclosed and accessed by a stairway flanked by stone lions, inviting visitors upward.

Above the podium, a colonnade of 36 slender columns, arranged roughly ten per side with shared corner columns, surrounded a solid central block. This stone core bore the massive weight of the pyramidal roof, which rose with 24 steps to form the upper third of the mausoleum’s height. At the very top stood a quadriga sculpture—a chariot drawn by four horses—that carried representations of Mausolus and Artemisia, crowning the entire structure with dynamic elegance. Archaeologists uncovered fragments of a large stone chariot wheel from this rooftop sculpture, measuring close to two meters in diameter.

Today, only parts of the mausoleum’s foundation and scattered broken sculptures remain in situ at the site. Many of the richly carved reliefs and statues recovered during 19th-century excavations are preserved in the British Museum, while polished white marble blocks have been integrated into the walls of Bodrum Castle, repurposed by the Knights of St John in the late 1400s. Inscriptions found on the site, including the remarkable quadrilingual text bearing Xerxes I’s name on a calcite jar, confirm the Carian rulers’ relationship with the Persian imperial authority.

Overall, the surviving elements at Halicarnassus provide critical insight into a unique fusion of Greek artistic traditions and Persian imperial culture as expressed through one of the most celebrated funerary monuments of the ancient world.