Diocletian’s Palace, Split: A Roman Imperial Residence and Urban Core in Dalmatia

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Croatia

Civilization: Byzantine, Roman

Remains: Civic

Context

Diocletian’s Palace is situated at the core of modern Split, a coastal city in Dalmatia, Croatia, positioned on the northern shore of the Adriatic Sea. The site occupies a peninsula adjacent to Split’s ancient harbor, where a narrow coastal plain meets the karstic hinterland rising inland.

Constructed in the late third century CE under Emperor Diocletian, the palace functioned within the Roman imperial system during Late Antiquity and the early Byzantine period. Archaeological and historical evidence documents a significant demographic shift in the seventh century, when refugees from the nearby city of Salona settled within the palace walls. This resettlement initiated the transformation of the complex from an imperial residence into a fortified urban quarter, which persisted through the medieval era and into early modern times.

Substantial portions of the original Roman structure survive today, integrated into Split’s contemporary urban fabric. Systematic archaeological excavations in the twentieth century have revealed stratified layers of Roman, medieval, and later modifications. Conservation and restoration efforts since the mid-twentieth century have aimed to stabilize and preserve the palace. In recognition of its exceptional preservation and cultural significance, the historic city of Split, centered on Diocletian’s Palace, was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

History

Diocletian’s Palace represents a unique architectural and historical monument reflecting the late Roman Empire’s political and military strategies. Erected at the turn of the fourth century CE as the retirement residence of Emperor Diocletian near his birthplace, the palace combined fortified military features with luxurious residential quarters. Over subsequent centuries, it evolved from an imperial stronghold into the nucleus of the medieval city of Split, embodying the region’s complex history of imperial administration, religious transformation, and population shifts.

Imperial Roman Period (Late 3rd – Early 4th Century CE)

In the late third century CE, the Roman Empire underwent extensive reforms under Emperor Diocletian, who sought to reinforce imperial authority through administrative reorganization and enhanced military defenses. Around 295 CE, construction commenced on a fortified palace near Spalatum (modern Split), within the province of Dalmatia, close to the provincial capital Salona. The palace’s design integrated the characteristics of a Roman legionary fort with those of an opulent villa, enclosed by massive limestone walls featuring sixteen projecting towers and four principal gates oriented to cardinal points.

The internal layout was organized around two main streets: a decumanus running east-west and a cardo running north-south, dividing the complex into northern and southern sectors. The southern sector contained the emperor’s private apartments, bath complexes, and religious edifices, including the Peristyle courtyard, the mausoleum (later converted into the Cathedral of Saint Domnius), and temples dedicated to Jupiter and Aesculapius. Construction materials were predominantly sourced locally, such as white limestone from the island of Brač and tufa from nearby riverbeds, supplemented by imported decorative elements including Egyptian granite columns and ancient sphinxes dating to the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III. Diocletian formally abdicated in 305 CE and retired to this palace, residing there until his death in 312 CE. The palace remained imperial property thereafter, occasionally serving as refuge for exiled members of the imperial family.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–7th Century CE)

Following Diocletian’s death, the palace continued to function as an administrative and residential center within the late Roman and early Byzantine provincial framework. Dalmatia remained under Eastern Roman control, with the palace hosting provincial governors and notable exiles such as Julius Nepos, who was assassinated near Salona in 480 CE, possibly within the palace precincts. During this period, the complex incorporated a state-operated textile manufactory producing woolen fabrics for military and administrative use, likely situated in the northern sector alongside residential and service areas.

Water supply was maintained by a substantial aqueduct drawing from the Jadro River, with a capacity exceeding the palace’s domestic needs, supporting both residential and industrial functions. The Christianization of the region is evidenced by the conversion of pagan temples into churches, including the transformation of the mausoleum into the Cathedral of Saint Domnius. Small churches were established above several gates, such as St. Martin’s Church above the North Gate, reflecting the growing veneration of local saints like Saint Domnius and Saint Anastase. The destruction of Salona in the seventh century during Avar and Slavic incursions precipitated a demographic shift, as refugees sought shelter within the palace walls. This event marked the beginning of the palace’s evolution into a fortified urban settlement, laying the foundation for the medieval city of Split.

Early Medieval Period and Formation of Split (7th–14th Century)

In the aftermath of Salona’s destruction, the palace complex became the core of a new urban settlement inhabited by a mixed population of Roman descendants and Slavic settlers. The palace’s robust fortifications provided essential protection during a period of regional instability. It developed into the episcopal seat of the area, with the former mausoleum serving as the cathedral. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, the palace interior was extensively filled with medieval houses and civic buildings, reflecting the growth and urbanization of Split as a medieval city.

Architectural modifications during this period included the construction of the Romanesque bell tower of the Cathedral of Saint Domnius, which incorporated elements of the original Temple of Jupiter. The palace walls and gates were adapted for medieval defensive and religious functions, with additions such as chapels and bell towers. The original Roman fabric was extensively reused and integrated into the expanding urban fabric, which by the late Middle Ages extended beyond the palace walls.

Early Modern Rediscovery and Architectural Influence (16th–18th Century)

During the Renaissance and early modern periods, interest in Diocletian’s Palace was revived among scholars and travelers who documented its ruins. Early descriptions and drawings by figures such as Cyriaque d’Ancône and Antonio Proculiano contributed to preserving knowledge of the site. In the eighteenth century, the palace became a subject of architectural study that influenced the Neoclassical movement in Europe. The Scottish architect Robert Adam conducted detailed surveys and published measured drawings in 1764, assisted by the artist Charles-Louis Clérisseau. These works introduced the palace’s architectural forms and motifs into European design vocabulary.

Further detailed depictions were produced by the French painter Louis-François Cassas in the late eighteenth century, providing accurate visual records of the palace and its medieval context. This period marked a growing appreciation of the palace’s historical and artistic significance beyond its local setting.

Modern Conservation and Cultural Integration (20th Century to Present)

Scientific archaeological investigations throughout the twentieth century, led by scholars such as Georg Niemann, Ernest Hébrard, and later Croatian archaeologists Jerko and Tomas Marasović, have significantly advanced understanding of the palace’s structure and history. Excavations clarified the layout of key areas including the Peristyle, imperial apartments, and thermal complexes. Today, the palace remains a living part of Split, with approximately 3,000 residents inhabiting its walls alongside commercial and cultural activities.

Conservation efforts since the mid-twentieth century have focused on stabilizing the ancient fabric while accommodating modern urban life. Restoration projects have addressed structural integrity, cleaning, and adaptive reuse of historic buildings. The palace’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 underscores its exceptional preservation and cultural importance. Additionally, the site has gained contemporary cultural relevance as a filming location for international media productions, further highlighting its enduring significance.

Remains

Architectural Features

Diocletian’s Palace occupies an irregular rectangular plan approximately 215 meters east-west by 175 meters north-south. The complex is enclosed by massive limestone walls averaging 2.10 meters in thickness, constructed with dual masonry facings and a rubble core. The exterior facing consists of carefully dressed white local limestone blocks assembled without mortar but secured by iron clamps. The upper section of the walls is thinner, about 1.15 meters thick, and pierced by arched embrasures measuring approximately 2 meters wide and 3.1 to 3.9 meters high. A simple S-shaped cornice runs along the perimeter, adapting to the terrain’s slope. The southern sea-facing wall is unfortified and distinguished by an arcaded gallery on its upper floor, featuring 42 arcades and 44 engaged columns, interrupted by loggias and wider openings corresponding to large rooms above.

The fortifications include sixteen projecting towers on the western, northern, and eastern facades. These comprise square corner towers characteristic of Roman legionary forts, octagonal towers flanking the three main land gates, and intercalated square towers. Access to the towers was provided by passages within the wall thickness at ground and upper levels. The southwestern corner tower was destroyed around 1550 due to undermining by the sea. The palace’s internal layout is organized by two main streets: a central east-west street (decumanus) and a north-south street (cardo), dividing the site into northern and southern sectors.

Key Buildings and Structures

North Gate (Porta Septemtrionalis)

Constructed in the late 3rd to early 4th century CE, the North Gate served as the principal land entrance facing the ancient city of Salona. It is the likely gate through which Emperor Diocletian entered the palace after his abdication in 305 CE. The gate’s original Roman structure remains visible, though it is surmounted by the 7th-century Church of St Martin, built within the gate’s upper sentry corridor. The church preserves early medieval architectural elements integrated into the Roman fabric and remains accessible.

East Gate (Porta Orientalis)

The East Gate, dating to the late 3rd or early 4th century CE, functioned as a secondary land entrance facing east toward Epetia (modern Stobreč). In the 6th century, a small church dedicated to St Apolinar was constructed above the gate within the sentry corridor. The gate and adjacent wall structures were later incorporated into various medieval buildings, including the now-destroyed Church of Dušica. The Roman masonry of the gate and adjoining walls remains partially preserved.

West Gate (Porta Occidentalis)

Built in the late 3rd to early 4th century CE, the West Gate was originally a military entrance for troop movements. It is the only gate continuously used from antiquity to the present. The original lintel bore a relief of Nike, which was removed during the 5th-century Theodosian persecutions and replaced by a Christian cross. Above the gate, a 6th-century church dedicated to St Teodora was established, coinciding with the influx of refugees in the early medieval period. The gate’s Roman masonry and defensive features remain largely intact.

South Gate (Porta Meridionalis)

The South Gate, constructed around 295–305 CE, is the smallest of the four principal gates and faces the Adriatic Sea. It originally served as the emperor’s private sea gate, providing access through basement rooms of the imperial apartments. The gate’s Roman stonework survives, though it lacks fortifications present on the land-facing sides. The gate connects directly to the southern palace complex.

Peristyle

The Peristyle courtyard, built circa 295–305 CE, is an oblong paved space approximately 27 meters long and 13.5 meters wide. It is bordered by arcades supported by columns about 5.25 meters high. Twelve columns are made of Egyptian red granite, while the remainder are marble, possibly cipolin from Euboea. The Peristyle forms the northern access to the imperial apartments and connects to the Vestibule to the south, the mausoleum (now Cathedral of Saint Domnius) to the east, and three temples to the west. Originally, the arcades were enclosed by 2.4-meter-high openwork balustrades (transennes), one of which was still visible in the 18th century.

The southern side features a monumental tetrastyle porch with four red granite columns topped by Corinthian capitals, supporting a fronton and architrave with a central arch known as the “Syrian fronton” motif. Two flights of stairs provide access to lateral openings, while the central opening was blocked by a transenne, creating a tribunal-like space. The courtyard floor lies lower than adjacent monuments and is surrounded by three steps on three sides.

Mausoleum (Cathedral of Saint Domnius)

Constructed around 295–305 CE, the mausoleum occupies the southeast corner of the palace within a rectangular enclosure measuring 32 by 39 meters. The structure is an octagon with sides 7.6 meters long and walls 2.75 meters thick, resting on a podium 3.7 meters high. The podium contains a vaulted crypt 13 meters in diameter, accessible via a narrow southwest passage and lit by three ventilation slits near the top. The crypt’s interior is undecorated and partly obstructed by eight inward-projecting buttresses. The circular chamber above measures 13.35 meters in diameter and 21.5 meters in height, featuring alternating semicircular and rectangular niches. Eight red granite columns from Aswan with Corinthian capitals and an architrave form a decorative order 9.06 meters high.

Above this is a smaller order of eight columns (four porphyry and four grey Egyptian granite) with composite and neo-Corinthian capitals, supporting a second architrave, reaching 13.91 meters to the dome base. The hemispherical dome, 1.25 meters high, is constructed of locally made bricks stamped “DALMATI” with a double-shell system and lacks an oculus. It was likely originally covered with mosaic and roofed with an eight-sided tile roof topped by a pine cone supported by four animal figures. The floor was paved with black and white marble. Two granite sphinx statues flank the entrance stairs. The mausoleum was converted into a church in the Middle Ages, which contributed to its preservation. Restoration took place between 1880 and 1885. Sculpted friezes inside depict hunting scenes, Erotes, garlands, and masks. Two clipeate portraits above the entrance niche are identified as Diocletian and a female figure possibly representing Tyché of Aspalathos.

Temple of Jupiter

Located at the southwest corner of the palace, the Temple of Jupiter was constructed around 295–305 CE within a temenos approximately 44 meters long and 21 meters wide. The temenos included a small tetrastyle prostyle Corinthian temple facing the Peristyle and two circular structures in the northeast and southeast corners, possibly altars, now preserved only as foundations. The temple podium measures 21 by 9.3 meters and stands 2.5 meters high. While the pronaos and façade are lost, the cella walls remain well preserved, featuring pilasters and Corinthian capitals at the corners. The cella is 11.4 meters long, with a richly decorated door 2.5 meters wide and 6 meters high, adorned with sculpted foliage, children picking grapes, and birds. The cornice includes Corinthian modillions decorated with sculpted heads representing tritons, Helios, Heracles, Apollo, winged Victories, and an eagle. The vaulted barrel ceiling consists of three rows of carefully fitted stone slabs carved with coffered patterns and decorated with human heads and rosettes, comparable to the Temple of Venus in Rome. The cult statue was likely Jupiter. The temple podium contains a crypt accessed by a narrow rear passage, though its function remains unknown.

Vestibule

The Vestibule is a large circular chamber (rotunda) approximately 12 meters in diameter and 17 meters high, constructed around 295–305 CE. It is located behind the monumental porch on the south side of the Peristyle. The walls are built in opus mixtum, alternating rubble and brick courses. Four semicircular niches open on either side of the north and south entrances. Originally, the chamber was illuminated by small high windows, and the vaulted ceiling was likely decorated with colored glass mosaics. The rotunda is inscribed within a square building with thick corner walls housing spiral staircases to upper and lower levels. The basement level contains four entrances leading to the east and west baths, the Peristyle, and the substructures beneath the imperial apartments.

Imperial Apartments (Private Apartments)

Constructed circa 295–305 CE, the imperial apartments extend along the entire south facade, approximately 40 meters deep, resting on vaulted substructures up to 8 meters high. The main entrance aligns with the southern passage of the Vestibule, leading to a large rectangular hall measuring 31 by 12 meters, which connects the Vestibule to a long gallery along the south facade. Two light wells flank the entrance hall, separating it from two rows of small vaulted rectangular rooms approximately 4.3 by 5.25 meters, opening onto a vaulted corridor.

The eastern half contains a large octagonal room with niches, identified as the main dining room (triclinium), aligned with a large southern facade opening. The western half includes the largest rectangular hall, 32 by 14 meters, with a north-end apse, vaulted by groin vaults supported on six massive pillars arranged in two rows, creating three aisles. This hall is illuminated by two symmetrical light wells and likely served as the main audience chamber. The western end contains fourteen small rooms of various shapes, some with apses or circular/cruciform plans, probably the most private residential quarters. Two small bath complexes lie north of the apartments, one adjacent to the west halls and the other to the east halls; their substructures are well preserved despite centuries of infill.

Cellars (Substructures)

The cellars beneath the imperial apartments, dating to the early 4th century CE, represent one of the best-preserved ancient vaulted substructure complexes worldwide. Barrel-vaulted stonework supports the upper floors, with well-preserved ground-floor substructures allowing reconstruction of the upper layout. These substructures provided a stable foundation for the apartments above and included storage and service spaces.

Baths

Two modest-sized bath complexes with their own exercise yards (palaestrae) and service rooms are located in the narrow space between the northern temenos enclosures and the southern private apartments. Constructed around the early 4th century CE, the baths include identified hypocaust heating systems and a furnace (praefurnium) for the western baths. The baths likely functioned until the early 6th century when the aqueduct supplying water was damaged. Their substructures remain partially preserved despite infill and later modifications.

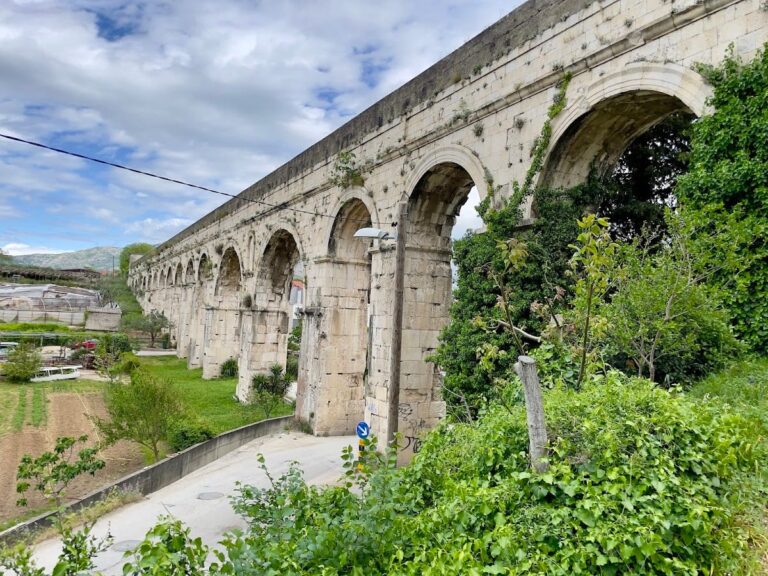

Aqueduct

The aqueduct, built in the late 3rd century CE, supplied water from the Jadro River approximately 9.7 kilometers away. The best-preserved section is an underground structure crossing the dry Dujmovača valley, consisting of 28 arches each about 16.5 meters high. The aqueduct’s estimated water flow capacity is about 13 cubic meters per second (one million cubic meters per day), considered oversized for the palace alone. This capacity suggests it also served a large state textile manufactory hypothesized to have been located in the northern half of the palace.

Egyptian Sphinxes

The palace was decorated with numerous granite sphinxes dating to approximately 3,500 years ago from the time of Pharaoh Thutmose III. Three sphinxes survive: one located on the Peristyle, a headless one in front of the Temple of Jupiter, and a third housed in the city museum. These sphinxes have funerary connotations and likely served as tomb guardians within the palace complex.

Other Temples

Three temples originally stood west of the Peristyle. Two are now lost, while the third, originally the Temple of Jupiter, was converted into a baptistery during the Christian period. The Temple of Aesculapius lies just west of the Peristyle and features a semi-cylindrical stone block roof that remained leakproof until the 1940s when it was covered with lead. This temple has undergone recent restoration efforts.

City Walls and Fortifications

The palace walls are heavily fortified on the land-facing sides (west, north, east) with projecting towers and four principal gates. The fortifications resemble 3rd-century Roman legionary forts, with a rectangular plan and projecting towers. The walls include embrasures for defense and a chemin de ronde (wall walk) with regularly spaced openings. These fortifications were adapted and reused continuously through the medieval period and remain a defining feature of Split’s old town.

Other Remains

The northern half of the palace, divided by the main north-south street (cardo), is less well preserved. It is thought to have housed soldiers, servants, and service facilities. Rectangular buildings near the perimeter walls, possibly storage magazines, survive but their function remains uncertain. Two small circular buildings within the temenos of the Temple of Jupiter survive only as foundations; their original purpose is unknown.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations and research have uncovered numerous artifacts spanning the Roman, early Christian, and medieval periods. Among these are inscriptions, architectural fragments, and sculptural elements. Egyptian granite sphinxes, dating to the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, were imported and placed as decorative and symbolic features within the palace. Inscriptions include dedicatory texts and portraits carved in the mausoleum, identifying figures such as Diocletian and possibly Tyché of Aspalathos. Architectural fragments include capitals, columns, and cornices made from imported materials such as Egyptian granite and marble from Brač and Euboea.

Archaeological layers have revealed tools and domestic objects associated with the palace’s residential and industrial functions, including evidence of a state-run textile workshop producing woolen fabrics for the army and administration. Pottery and coins from the late Roman and early Byzantine periods have been found in various sectors, supporting the chronology of occupation and reuse. Religious artifacts include Christian crosses and small churches built above gates, reflecting the region’s Christianization.

Preservation and Current Status

Large portions of the original palace complex survive integrated into the modern urban fabric of Split. The walls, gates, and major monuments such as the Peristyle, Vestibule, and mausoleum are well preserved, though some structures are fragmentary or partially restored. Restoration efforts since the mid-20th century have focused on stabilizing the built fabric, cleaning stone surfaces, and conserving architectural details. Some areas have undergone reconstruction using original materials where possible, while others remain stabilized but unrestored to preserve authenticity.

Environmental factors such as sea erosion contributed to the loss of the southwestern corner tower around 1550. Conservation programs have addressed structural integrity and adaptive reuse of historic buildings. The site’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 has supported ongoing preservation. Archaeological research continues to balance conservation with the palace’s role as a living urban space.

Unexcavated Areas

The northern half of the palace remains less thoroughly excavated compared to the southern sector. Surface surveys and stratigraphic excavations have identified building remains and possible industrial areas, but some structures, including rectangular buildings near the perimeter walls and small circular foundations within the Temple of Jupiter’s temenos, await further study. Modern urban development limits extensive excavation in some parts of the palace. No detailed plans for future large-scale excavations have been publicly documented, with conservation priorities focusing on known and accessible areas.