Calatrava la Vieja: A Historic Fortress in Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: cultura.castillalamancha.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Calatrava la Vieja is located near Carrión de Calatrava in modern Spain. It was established by the Umayyads at the end of the 8th century as a fortress that controlled the important route between Córdoba and Toledo within the territory of al-Andalus.

For about four centuries, Calatrava la Vieja belonged to the Emirate and later the Caliphate of Córdoba. Between 853 and 1147, the site was the capital of a large administrative region after undergoing significant reconstruction under al-Hakam, the brother of Emir Muhammad I. Following the collapse of the Caliphate in the early 11th century, the fortress became a contested stronghold among the Taifa kingdoms of Seville, Córdoba, and Toledo. Amid these struggles, Calatrava la Vieja emerged as the primary Muslim fortress facing the Christian Kingdom of Castile, especially after Toledo was captured by Christian forces in 1085 and the Almoravid dynasty arrived in 1086.

In 1147, Alfonso VII of León and Castile seized Calatrava la Vieja. He initially granted it to the Knights Templar, who soon abandoned the site. In 1158, King Sancho III passed control to Abbot Raymond of Fitero, who founded the Order of Calatrava at the fortress. This military order was the first major Iberian order established to defend Christian territory and manage frontier lands.

The fortress later fell to the Almohads in 1195 following their victory at the Battle of Alarcos. The Almohads held the site for 17 years until Castilian forces recaptured it in 1212 during the campaign culminating in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, a decisive turning point in the Christian reconquest. Shortly after, in 1217, the Order of Calatrava moved its headquarters approximately 60 kilometers south to the Castle of Dueñas, known as Calatrava la Nueva. This relocation initiated a gradual decline of Calatrava la Vieja, which was eventually abandoned by the early 15th century when the military commander of the Order settled at nearby Carrión de Calatrava.

Since the late 20th century, archaeological studies and restoration efforts have revealed its importance as one of the most significant sites of Islamic origin in Spain, uncovering the layers of history accumulated through centuries of military, religious, and administrative use.

Remains

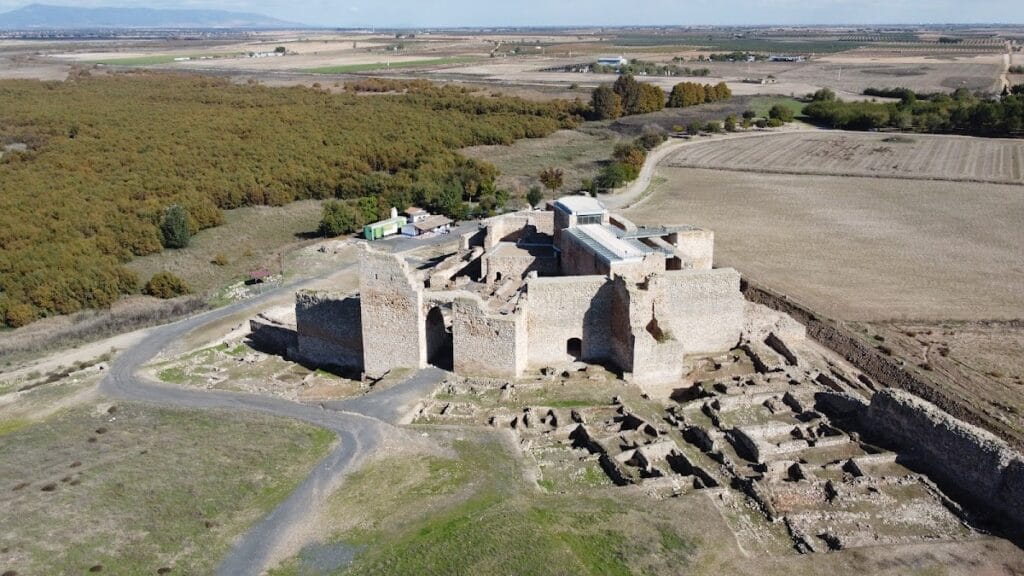

Calatrava la Vieja occupies an oval-shaped plateau of about five hectares on the left bank of the Guadiana River. Natural defense is provided by the river to the north, with the rest of the site encircled by a deep dry moat carved mainly from solid rock. This moat stretches over 750 meters and reaches depths of around 10 meters, effectively turning the settlement into an island. Surrounding this defensive ditch are approximately 1,500 meters of walls dating largely to the Umayyad period. The walls contain at least 44 flanking towers, mostly hollow with quadrangular shapes, while on the eastern side of the central fortress (alcázar) stand two notable pentagonal towers. Tower size and spacing vary with larger, more widely spaced structures on the southern front and smaller, solid towers placed closer together on the western side.

The site is divided into two main sectors separated by a large dividing wall. To the east lies the alcázar, a triangular area covering about one hectare that served as the seat of power and the strongest line of defense. The remainder of the enclosure comprises the almedina or medina, where a wall fortified with over 40 towers surrounds the urban area. Outside these walls, the suburbs, known as arrabales, contain evidence of industrial and artisanal spaces, a cemetery, scattered dwellings, and a mosque near what is today the Ermita de la Encarnación.

Within the alcázar, archaeological remains show several construction phases. Early segments include adobe, brick, and rammed earth walls predating 853. Later, in the 9th century during Muhammad I’s rule, extensive reconstruction introduced large entrance towers, a triumphal arch, and pentagonal towers integrated into an advanced hydraulic defense system. Between 1147 and 1158, during the brief Templar occupation, an unfinished dodecagonal apse of a church was constructed here. Subsequent centuries saw the addition of a church and vaulted annexes used by the Order of Calatrava including a smithy built over earlier foundations.

One of the site’s distinctive features is its sophisticated hydraulic defense system. Four waterworks known as corachas lifted water from the moat into the fortress. Part of this water was channeled to a pentagonal tower, called the castellum aquae, where it was propelled through ceramic pipes back into the moat under pressure. This mechanism was unique in medieval military architecture and is believed to have been a symbol of Umayyad technological skill and authority. Two hollow pentagonal towers at the eastern alcázar date to 854 and played key parts in this system. One functioned as a water castle without direct internal access, while the other was a control tower accessible from the alcázar. A third tower originally built as an albarrana — a detached defensive tower connected by a bridge — was later reshaped into a pentagonal form, possibly to support heavy siege equipment.

The southern city gate features a 9th-century bent, or “in recodo,” design. It is reached via a bridge spanning the moat and is preceded by a frequently used postern gate, a smaller secondary entrance. The alcázar includes a comparable bent gate that provided controlled access to the river through an external ramp.

Within the almedina, remains of homes and an Almohad-period paved street have been uncovered. The urban layout includes typical Islamic elements such as mosques, baths, shops, and pottery workshops, reflecting its role as both a military and civilian center.

While the moat and defensive walls are in many places covered by debris and earth, their substantial size and course remain visible. The river protects the northern moat bank, while the dry ditch and walls defend the remaining perimeter.

Archaeological research has also identified prehistoric layers of occupation beneath the fortress, though no remains from Roman or Visigothic settlement have been found, likely due to the ancient area’s poor health conditions.

Additionally, structures from the brief Templar presence and the later era of the Order of Calatrava persist inside the alcázar, including the unfinished church and related buildings, tying the site to important chapters in medieval military and religious history.