Myra: An Ancient Lycian City in Turkey

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

The ruins of Myra are located in the municipality of Demre in Turkey. This ancient city was founded by the Lycians, an indigenous people of the region now known as Antalya Province, and developed along the banks of the river Myros.

Myra rose to prominence as a member of the Lycian League between 168 BC and AD 43, recognized by ancient geographer Strabo as one of the league’s largest cities. The city was initially devoted to its protective goddess Artemis Eleutheria, alongside other deities such as Zeus, Athena, and Tyche. Roman author Pliny the Elder mentioned a spring named Curium near Myra, which was dedicated to Apollo and known for its oracular fish, highlighting the city’s religious significance.

Over time, Myra came under the rule of various imperial powers. It passed from Lycian control to become part of the Ptolemaic and then Seleucid domains before integrating into the Roman Empire. Despite these changes, Myra maintained a degree of local autonomy under Roman rule and was culturally connected to the Greek-speaking Koine world. During the early Christian era, the city emerged as a religious center, notably serving as the episcopal seat of Saint Nicholas in the 4th century, a figure later famed as the inspiration for Santa Claus.

In the medieval period, Myra experienced military conflict. It fell to Abbasid forces during a siege in 809 AD, and later came under the authority of the Seljuk Turks in the reign of Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus (1081–1118). In 1087, sailors from the Italian city of Bari transported the relics of Saint Nicholas from Myra to their city. Centuries later, the Christian population of Myra was expelled in 1923 following the official population exchange between Greece and Turkey, leading to the abandonment of key religious buildings.

Modern archaeological work began in 2009 using technologies such as ground-penetrating radar. Excavations have since uncovered significant structures, including a well-preserved chapel dating from the 13th century and terracotta sculptures estimated to be over 2,000 years old. The nearby ancient harbor settlement of Andriake has also been the focus of ongoing digs since that time.

Remains

The archaeological site of Myra contains notable constructions that reflect its long history and varied cultural influences. Much of the city was built using local stone, with structures often carved directly into cliff faces or constructed in large masonry forms.

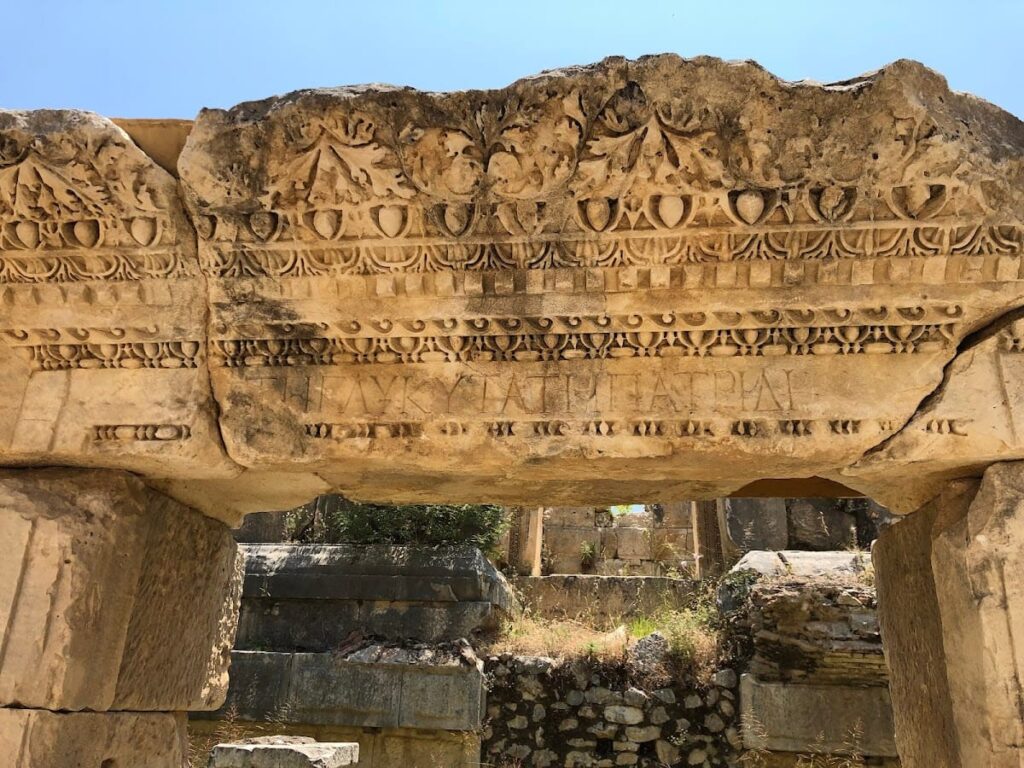

Among the most remarkable features is a Roman semi-circular theatre dating from the 1st to 2nd centuries BCE. Although an earthquake in 141 CE devastated the original theatre, it was rebuilt and continued to be used. Inside, seating rows bear inscriptions identifying specific places, including one marking the spot reserved for a food vendor named Gelasius, offering insight into the social life of the city’s amphitheater.

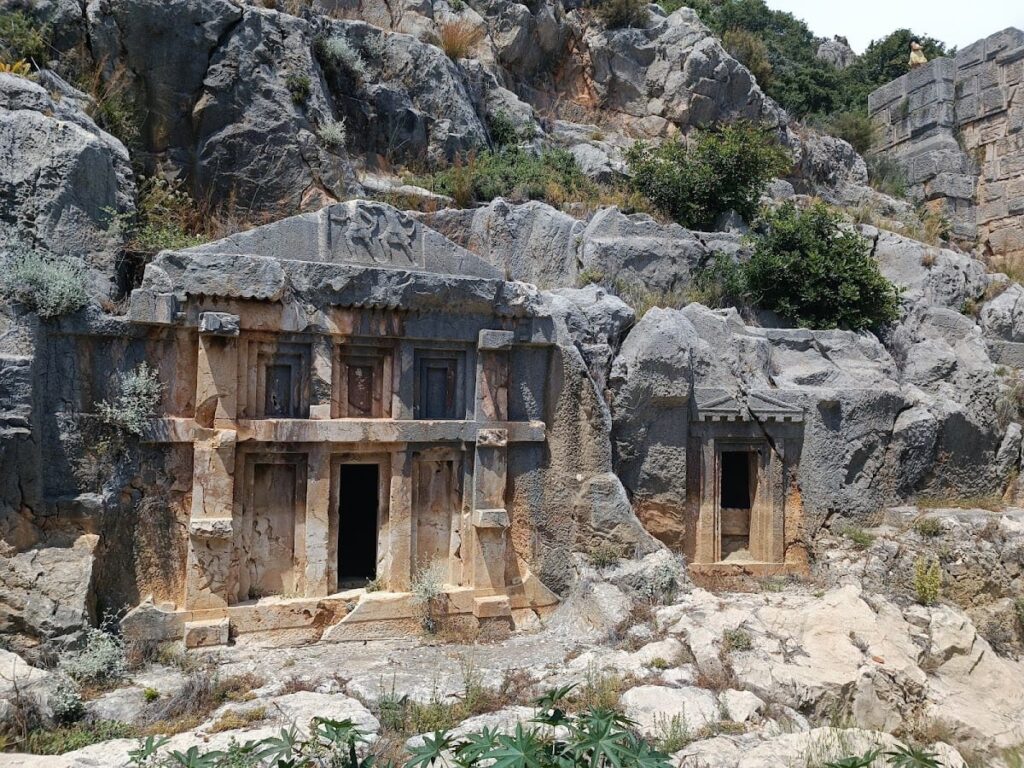

Myra is also famous for its two necropoleis, or burial areas, where tombs are carved into vertical cliffs. These rock-cut tombs adopt the form of temple facades, exemplifying Lycian funerary architecture. The river necropolis includes the so-called “Lion’s Tomb” or “Painted Tomb,” which in the 19th century was noted for its vivid red, yellow, and blue paint, hinting at the original decorative styles that adorned Lycian tombs.

The ancient harbor at Andriake retains substantial remains connected to maritime trade. A large granary from the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE) stands measuring 56 by 32 meters and features seven separate rooms. Adjacent to this granary, a significant mound of Murex shells demonstrates the production of the valuable purple dye for which the ancient Mediterranean was famous. Excavations at Andriake have also restored the harbor’s market, an agora, a synagogue, and a large cistern—engineered reservoirs measuring 24 by 12 meters with a depth of six meters to supply water. Exhibited outside the site’s museum in the restored granary are a 16-meter ancient Roman boat, a crane, and a cargo vehicle, emphasizing the port’s active commerce.

Central to the Christian heritage of Myra is the Church of Saint Nicholas. Initially constructed between the 5th and 6th centuries near the saint’s burial place, it was extensively rebuilt from the 8th century onward as a basilica featuring three aisles and topped with a dome. The church floor is decorated with opus sectile, an artistic technique involving inlaid colored marble mosaics. Frescoes illustrating episodes from Saint Nicholas’s life once adorned its walls, and the saint’s sarcophagus is crafted from an ancient Greek marble coffin reappropriated for Christian use. Additional surviving structures around the church include a baptistery attached to the inner narthex (the entrance hall) and two chapels located to the south of the main basilica.

After partial excavation in 1963, restoration initiatives began in 1989 with support from both Turkish authorities and international collaborators. In 2007, the site received permission to resume the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, allowing religious ceremonies to be held once again after centuries of interruption.