Sabratha: An Ancient Phoenician and Roman City in Libya

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Libya

Civilization: Byzantine, Phoenician, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Sabratha is situated on the Mediterranean coast in present-day Sabratah, within Libya’s Zawiya District. The site occupies a low-lying coastal plateau overlooking a small sandy bay west of Tripoli, providing access to maritime routes across the central Mediterranean. The surrounding landscape includes fertile hinterlands that supported agricultural activities, linking the city to inland resources.

Archaeological evidence indicates that Sabratha was founded during the sixth to fifth centuries BCE as a Phoenician settlement. Subsequent layers reveal Carthaginian influence through imported ceramics and urban features. The city expanded significantly during the Roman period, with major construction phases from the late Republic through the third century CE. Stratigraphic data confirm continued occupation into Byzantine and early Islamic times, although later periods show diminished urban development and maintenance.

European travelers documented visible ruins from the eighteenth century onward, while systematic archaeological investigations began in the early twentieth century under Italian direction. Later excavations by Libyan and international teams have enhanced understanding of the site’s urban fabric and monumental architecture. Many public buildings survive as exposed ruins with in situ mosaics and inscriptions. Sabratha was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982, though ongoing environmental challenges, including coastal erosion, threaten its preservation.

History

Sabratha’s historical trajectory spans over a millennium. Initially established as a Phoenician trading post, it became integrated into the Carthaginian maritime network. After the Punic Wars, the city passed through Numidian and Roman control, flourishing particularly under Roman imperial administration. The city declined following seismic events and political upheavals in Late Antiquity, experienced a limited Byzantine revival, and diminished further after the Islamic conquests. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence documents these phases, illustrating Sabratha’s evolving role within Mediterranean empires and its gradual urban contraction.

Phoenician and Carthaginian Period (6th century BCE – 2nd century BCE)

Founded around the sixth century BCE as the Phoenician settlement Tsabratan, Sabratha was likely established atop an earlier Berber community, indicating indigenous roots preceding Phoenician colonization. The city functioned as a fortified coastal port facilitating trade between the African interior and Mediterranean markets. Its urban layout featured irregular street patterns characteristic of Libyco-Punic cities, with some Hellenistic architectural influences evident in religious and funerary structures. Material culture, including imported pottery, confirms Sabratha’s incorporation into the Carthaginian maritime and commercial sphere until the second century BCE.

Numidian and Early Roman Period (4th century BCE – 1st century BCE)

Following Carthaginian decline after the Punic Wars, Sabratha came under the control of the Numidian kingdom, ruled by King Massinissa and his successors. The city aligned politically with Rome in 111 BCE, marking its integration into the Roman sphere of influence. During this period, Sabratha adopted a more regular urban plan, characterized by a rectangular street grid extending from the harbor to the forum, reflecting Roman urban design principles. The necropolis expanded with large mausoleums dating to the second century BCE, indicating social stratification and elite burial customs. By 157 CE, epigraphic evidence confirms Sabratha’s elevation to municipium status and later to a Roman colony, signifying full administrative incorporation into the empire.

Imperial Roman Period (2nd – 3rd centuries CE)

The second and third centuries CE represent Sabratha’s apogee under Roman rule, particularly during the Severan dynasty, which had familial ties to the region. The city nearly doubled in size, undertaking extensive monumental construction. Public works included a large theater with a seating capacity of approximately 5,000, restored in the twentieth century, and a forum surrounded by tabernae (shops) and a basilica judiciale used for legal proceedings. Temples dedicated to Liber Pater (a Punic form of Dionysus and Severan family deity), Serapis, and Isis illustrate religious syncretism and imperial cult practices. The city’s public baths near the shore featured elaborate mosaics and sophisticated architectural design. An amphitheater located about one kilometer from the city center could accommodate up to 20,000 spectators and hosted gladiatorial games sponsored by local magistrates, as attested by inscriptions. Additionally, mosaics found in Ostia, Rome’s port, depict an elephant symbolizing Sabratha’s role in trans-Saharan trade, including the export of wild animals for Roman spectacles.

Late Antiquity and Vandal Period (4th – 6th centuries CE)

The earthquake of 365 CE caused significant damage to Sabratha, initiating a period of urban decline. In the fifth century, the city came under Vandal control, during which many urban areas were abandoned. Under Byzantine administration in the sixth century, Sabratha experienced a modest revival, marked by the construction of defensive walls enclosing a reduced urban core and the erection of several churches. The basilica judiciale was converted into a Christian church in the early fifth century, incorporating a baptistery and a tomb with a ring-bearing figure in the apse, indicating the establishment of a bishopric. A new basilica constructed under Emperor Justinian I featured mosaic floors with geometric and vegetal motifs, praised by the historian Procopius of Caesarea. These developments reflect the city’s transformation into a Christian episcopal center during Byzantine rule.

Early Islamic and Post-Islamic Period (7th century CE onward)

Following the Muslim conquest, Sabratha’s prominence declined sharply as regional trade routes shifted to other ports. The city contracted to a small village, with monumental buildings falling into ruin over subsequent centuries. Archaeological layers from this period indicate reduced urban maintenance and limited new construction, marking the cessation of Sabratha’s role as a major urban center. Islamic cultural and religious practices gradually supplanted earlier Christian traditions, although evidence for early Islamic architecture at the site remains limited.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Phoenician and Carthaginian Period (6th century BCE – 2nd century BCE)

During its foundation as Tsabratan, Sabratha’s population consisted mainly of Phoenician settlers who integrated with indigenous Berber groups, forming a culturally hybrid society. Social organization likely included merchant families controlling maritime trade, artisans producing Punic-style ceramics, and religious elites overseeing cultic activities. Economic life centered on maritime commerce connecting the African interior with Mediterranean markets. The urban fabric featured irregular streets and fortifications typical of Libyco-Punic cities, while religious buildings displayed Hellenistic architectural influences. Diet comprised locally grown cereals, olives, and Mediterranean fish, supplemented by imported goods.

Roman Period (1st century BCE – 3rd centuries CE)

At its height, Sabratha’s population included Roman citizens, local Libyans, and merchants engaged in trans-Saharan trade. The city’s elevation to municipium and later colonia status granted administrative autonomy and integration into Roman provincial systems. Civic inscriptions record duumviri and other magistrates sponsoring public games, reflecting a complex social hierarchy with prominent elites and a diverse urban populace.

The economy thrived on maritime commerce, agriculture, and artisanal crafts. Public baths, olive presses, and workshops attest to industrial activity at household and urban scales. The amphitheater and theater hosted entertainment, while merchants exported exotic goods, including wild animals for Roman spectacles, as evidenced by mosaics in Ostia. Diet was rich in Mediterranean staples—bread, olives, fish, and wine—with archaeological evidence of olive oil production. Domestic interiors featured mosaics and frescoes, with houses arranged around courtyards. The forum served as the commercial and civic center, surrounded by shops and judicial buildings. Transport combined sea vessels and well-maintained roads facilitating regional connectivity. Religious life was pluralistic, with temples to Liber Pater, Serapis, and Isis alongside imperial cult worship. Sabratha functioned as a Roman colonia, a key administrative and commercial center within the province.

Late Antiquity and Vandal Period (4th – 6th centuries CE)

Following the 365 CE earthquake and later Vandal conquest, Sabratha’s population declined, with many urban areas abandoned. Remaining inhabitants included Christian communities led by bishops, as indicated by the conversion of the basilica judiciale into a church and the presence of baptisteries. Social organization shifted toward ecclesiastical leadership, with diminished civic magistracies. Economic activity contracted, focusing on subsistence agriculture and limited trade. Workshops and public amenities fell into disrepair, though Byzantine restoration introduced new churches and defensive walls enclosing a smaller urban core.

Olive cultivation and fishing likely persisted at reduced scales. Diet remained Mediterranean but simpler, reflecting economic hardship. Domestic spaces were less ornate, with Christian iconography replacing earlier pagan motifs. Markets and transport diminished, with fewer goods circulating. Religious life centered on Christianity, with liturgical practices, episcopal governance, and church-sponsored education becoming prominent. Under Byzantine rule, Sabratha served as a modest episcopal center, maintaining religious significance despite its reduced urban footprint.

Early Islamic and Post-Islamic Period (7th century CE onward)

After the Islamic conquest, Sabratha’s population contracted further, becoming a small village with limited urban functions.

Remains

Architectural Features

The archaeological remains at Sabratha document its evolution from a Phoenician trading post with irregular Libyco-Punic street layouts and fortifications to a Roman city characterized by a regular rectangular grid plan extending from the harbor to the forum. Construction materials primarily include local sandstone and stone, with ashlar masonry employed in major public buildings. The city expanded significantly during the second and third centuries CE, then contracted in Late Antiquity, with Byzantine defensive walls enclosing a smaller urban area. Coastal erosion has damaged harbor installations and an olive press near the shore. Many monumental buildings survive as exposed ruins or partial reconstructions, preserving mosaics and inscriptions in situ.

The site comprises civic, religious, entertainment, and funerary structures. Public buildings such as the forum, basilica, temples, theater, and amphitheater are prominent. Residential quarters and economic installations are less well preserved but identified through surface remains and architectural fragments. Byzantine walls date to the fifth and sixth centuries CE, reflecting urban contraction after the fourth century. The overall remains illustrate a city that grew in wealth and connectivity during the Roman imperial period before declining in Late Antiquity and the early Islamic era.

Key Buildings and Structures

Theater of Sabratha

Located in the eastern sector of the site, the Roman theater dates to the second and third centuries CE. It has an estimated seating capacity of approximately 5,000 spectators. The theater retains a three-storey architectural backdrop (scaenae frons) featuring a monumental colonnade and detailed bas-relief decoration along the stage front. Excavations beginning in 1927 uncovered the theater buried beneath sand and masonry rubble. Restoration by anastylosis was completed in 1937, reconstructing the stage wall colonnade and decorative elements. Adjacent to the theater are associated baths, known as the theater baths, which preserve black and white mosaic floors.

Amphitheatre of Sabratha

Situated about one kilometer west of the city center, the amphitheater dates to the second century CE. It is built into a natural depression, possibly a former quarry, and oriented east-west. The structure includes twelve visible rows of stone seating rising over ten meters in height; a third tier likely consisted of wooden stands supported by now-lost masonry vaults. The arena measures approximately 45 by 30 meters and is divided by a cross-shaped trench used for raising animals or scenery. Two large entrances stand at each end of the arena’s long axis, with several smaller doors around the perimeter accessed via an internal gallery. Archaeological evidence indicates four construction phases. An inscription records a duumvir who sponsored five days of gladiatorial games. The amphitheater was first described in 1912 and partially excavated in 1924.

Forum and Basilica

The forum was laid out in a rectangular grid plan from the first century BCE, extending southward from the harbor to the market area. It was originally bordered by a row of small shops (tabernae). On the southern side stood a basilica used for judicial purposes, measuring 48.5 meters long by 26 meters wide. The basilica featured an interior portico and an apse at one end, consistent with Vitruvian architectural descriptions. Under the late Antonine emperors in the late second century CE, the basilica was expanded to 72 meters in length. In the first half of the fifth century CE, it was converted into a Christian church, with additions including a tomb in the apse, an altar, and a baptistery. Byzantine restorations in the sixth century reduced the church’s size and added a new façade with three doors. A separate basilica was constructed under Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century, praised by Procopius of Caesarea. Its mosaic floor, decorated with stylized trees and geometric motifs, is preserved and displayed in the site museum.

Temple of Liber Pater

Located at the eastern end of the forum, the Temple of Liber Pater dates to the Severan dynasty period in the early third century CE. It is dedicated to Liber Pater, a deity associated with the Severan family and equivalent to Dionysus. The temple features three tall sandstone columns with Corinthian capitals. The columns stand on a podium accessed by a wide staircase oriented west to east. The capitals are simple sandstone drums covered with stucco motifs. Sandstone was used due to the unavailability of marble in North Africa at the time.

Temple of Serapis

Situated near the northwest corner of the forum, the Temple of Serapis dates to the Antonine period in the second century CE. It was surrounded by arcades and dedicated to Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity. The temple’s remains include foundations and partial wall structures, indicating a rectangular plan enclosed by colonnaded walkways.

Temple of Isis

Located closer to the sea, the Temple of Isis is part of a religious complex dating to the Antonine period in the second century CE. It is enclosed by a courtyard surrounded on all four sides by arcades and accessed by a simple staircase. Excavations began in 1934, with inscriptions found in 1937 and 1943 confirming its identification. Representations of Isis, Serapis, and Harpocrates were discovered within the complex. The temple’s remains include foundations, column bases, and parts of the surrounding arcade.

Libyco-Punic Building

This structure dates to the second century BCE and exhibits Libyco-Punic architectural features with Hellenistic influences. It has been largely reconstructed by Libyan archaeologists. The building shares strong similarities with the Libyco-Punic mausoleum of Dougga, including masonry style and decorative elements. The remains include walls and partial columns, reflecting the original irregular street layout.

Neo-Punic Tophet

A Neo-Punic sacred precinct, or tophet, has been excavated at the site. It consists of a walled enclosure containing urns and ritual deposits associated with funerary practices. The tophet dates to the late Punic period, prior to Roman dominance.

Public Baths (Thermes de l’Océan)

Located near the seashore and adjacent to the forum, the Ocean Baths date to the Roman imperial period, likely the second century CE. The baths preserve mosaic floors with colored geometric patterns, among the best preserved in Roman North Africa. The complex includes caldarium (hot rooms), frigidarium (cold rooms), and other bathing chambers arranged around a central courtyard overlooking the shore.

Christian Basilica of Justinian

Constructed under Emperor Justinian I in the sixth century CE during the Byzantine phase, this basilica features a mosaic floor decorated with stylized trees and geometric motifs. It was part of the city’s Christian episcopal center. The basilica’s remains include mosaic pavements, partial walls, and foundations. Procopius of Caesarea praised the building in his writings.

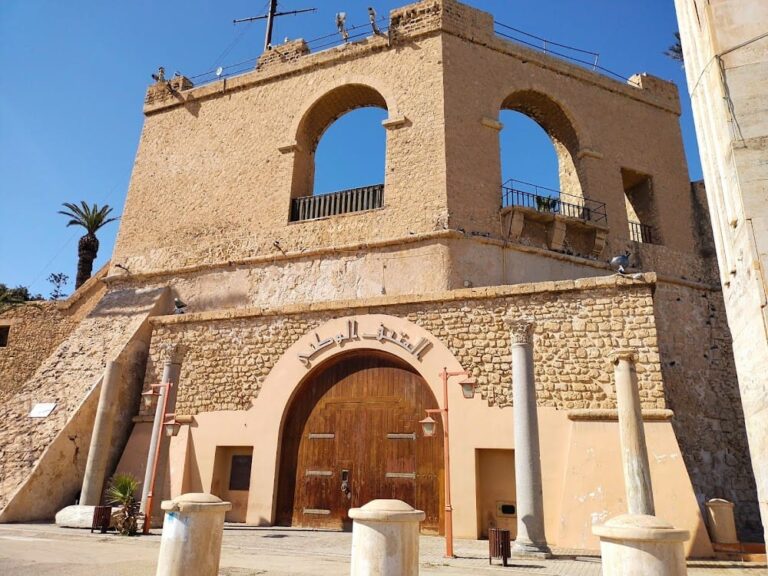

City Walls and Defensive Structures

Byzantine-era defensive walls date to the fifth and sixth centuries CE. These walls enclose a smaller urban area than the earlier Roman city, reflecting contraction after the fourth century. The walls are constructed of stone masonry and include towers and gates, though many sections survive only as foundations or low fragments.

Necropolis and Burial Monuments

Sabratha’s necropolis contains two large mausolea dating to the second century BCE, reflecting Punic funerary traditions. The burial area includes various Punic funerary monuments, inscriptions, and artifacts such as mosaics and statues recovered from tombs. The necropolis lies outside the main urban area and has been partially excavated.

Other Remains

Additional remains include surface traces and architectural fragments of elite domestic dwellings with mosaic floors, indicating residential quarters. An olive press building near the harbor is heavily damaged by coastal erosion. Harbor structures, including quays and breakwaters, also suffer from erosion and storm damage. Evidence of economic activity is present in ceramic debris, amphora fragments, glass shards, slag, and ash layers found in various parts of the site. The Roman city’s rectangular grid plan is visible in street alignments and foundation remains.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Sabratha have uncovered a wide range of artifacts spanning from the Phoenician through Islamic periods. Pottery assemblages include locally produced and imported amphorae and tableware from Phoenician, Punic, and Roman contexts. Inscriptions on stone and mosaic floors provide dedicatory formulas and references to local magistrates and deities. Coins from Roman emperors, including the Severan dynasty, have been recovered, indicating economic connections. Tools related to agriculture and crafts have been found in domestic and workshop areas. Domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels appear in household contexts. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels associated with temples of Liber Pater, Serapis, and Isis. These finds were made in sanctuaries, public buildings, and burial sites, reflecting the city’s diverse religious practices over time.

Preservation and Current Status

Many of Sabratha’s major structures survive as exposed ruins, though their preservation varies. The theater and amphitheater are among the best-preserved monuments, with the theater’s stage wall and colonnade largely reconstructed through twentieth-century restoration. The forum and basilica retain foundations and partial walls, with mosaic floors preserved in some areas. Temples survive mainly as foundations, columns, and partial walls. Byzantine walls are fragmentary but identifiable. Coastal erosion poses a significant threat to harbor structures and the olive press building. Some mosaics and inscriptions remain in situ, while others have been moved to the site museum for protection. Conservation efforts by Libyan authorities and international teams continue, focusing on stabilizing exposed ruins and mitigating environmental damage. The site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982 and placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2016 due to ongoing threats.