Qal’eh Dokhtar: An Early Sasanian Fortress near Firuzabad, Iran

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Low

Country: Iran

Civilization: Sassanid

Site type: Military

Remains: Fort

History

Qal’eh Dokhtar, or “Maiden’s Castle,” stands near Firuzabad in the municipality of Firuzabad, Iran. It was built by the Sasanians, an empire that rose to prominence in the early 3rd century CE, marking a transition from the preceding Parthian rule.

The fortress was constructed around 209 CE, likely under the direction of Ardashir I, who founded the Sasanian Empire. This period marks the final years of Parthian dominance under King Artabanus V, whom Ardashir I ultimately defeated. Before his conquest and establishment of the Sasanian dynasty, Ardashir I used Qal’eh Dokhtar as a strategic military stronghold and royal residence to oversee the region and protect the first Sasanian capital, Gur—today’s Firuzabad.

Following its initial use, the castle remained an important center for defense and administration in the early Sasanian era. It also served as a royal venue where guests were entertained, and festivities took place. Over time, the castle was succeeded in prominence by a nearby complex known as the Atashkadeh palace, located on the plains of Firuzabad. Local tradition recalls a secret cave passage within Qal’eh Dokhtar, reputedly connecting the fortress to Ardashir’s palace, which allowed for secure communication and supply during times of siege.

While the site did not sustain any recorded conquests after the early Sasanian era, its role evolved as the political and religious center shifted to larger constructions nearby. Qal’eh Dokhtar, however, remains a testament to the change from Parthian control to Sasanian rule and stands as an emblem of Ardashir I’s rise to power.

Remains

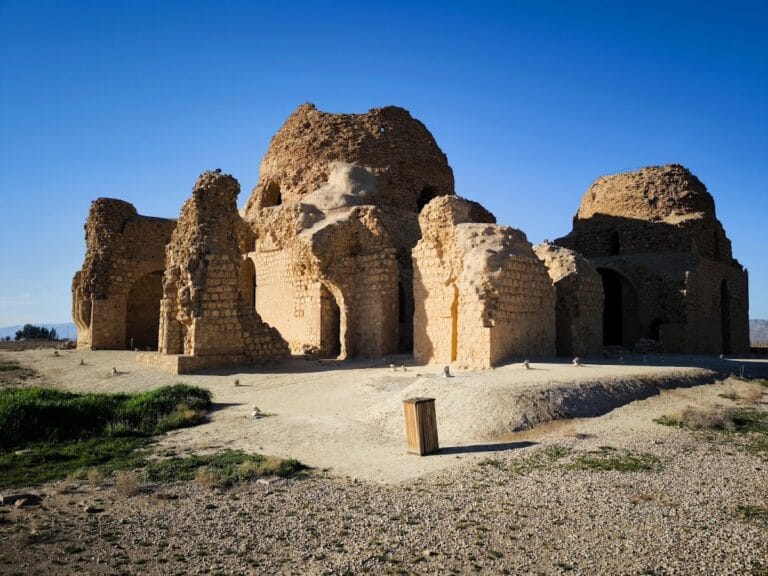

Qal’eh Dokhtar is situated on a mountainside that rises in three distinct terraces. The fortress’s design covers these levels, with its original entrance located on the lowest terrace. Visitors would have reached the entrance via a winding, stepped path that leads into a spacious central courtyard. This courtyard is enclosed on three sides by rectangular rooms vaulted with stone ceilings, while the fourth side opens onto the main palace area, reflecting a layout that combines both defensive and residential functions.

The principal palace structure within the castle features a large iwan—an architectural term referring to a vaulted hall open on one side—measuring approximately 14 meters wide and 23 to 24 meters in length. At its core lies a domed chamber, showcasing advanced engineering with thick supporting walls and accessible by a spiral staircase on the southern side. This dome was built using structural elements called squinches, which are architectural techniques allowing for the transition from a square room to a circular dome overhead, distinct from Roman methods. Flanking this grand hall are two smaller iwans, contributing to a complex spatial arrangement typical of early Sasanian palatial architecture.

The fortress’s construction utilizes large, precisely cut stones for the exterior facades, while rough river stones mixed with lime mortar compose the foundations and inner walls. Despite centuries of weathering and partial collapse, the defensive walls remain imposing, including a circular outer wall that encloses the palace area. The fortifications extend beyond this to incorporate advanced outworks reaching heights between six and seven meters. A prominent round tower, likely situated atop the hill, is thought to have served as a throne room or ceremonial chamber, underscoring the fortress’s royal associations.

Carved directly into the mountain is a stone water reservoir, intended to provide a secure supply of water to the fortress’s inhabitants during sieges, indicating careful planning for prolonged defense. One side of the castle includes the entrance to a cave, believed by local tradition to create a concealed passage connecting Qal’eh Dokhtar to Ardashir’s palace on the plains. This feature would have facilitated clandestine communication and movement, especially when the fortress was under threat.

Today, the path to the fortress involves a staircase of 308 steps, surviving as evidence of the original access route. Within the site, areas that once hosted the residential and defensive functions remain in situ, allowing for study of early Sasanian military architecture and palace design. This combination of natural topography and sophisticated construction illustrates the fortress’s dual role as a military bastion and symbol of nascent Sasanian statehood.