Petra: The Ancient Nabataean Capital in Jordan

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.visitpetra.jo

Country: Jordan

Civilization: Byzantine, Nabataean, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Petra is situated in southern Jordan near the modern town of Wadi Musa, occupying a natural basin carved into the sandstone plateaus of the Shara Mountains. The site’s topography is defined by steep cliffs and narrow gorges, including the prominent Siq, which channels seasonal water flows through the city. Local springs, combined with an extensive system of engineered dams, cisterns, and channels, provided a reliable water supply essential for sustaining a large population in this arid environment. The rugged sandstone landscape constrained urban development, encouraging the Nabataeans and later inhabitants to extensively utilize rock-cut architecture integrated into the cliffs.

Archaeological investigations have revealed continuous human activity at Petra from prehistoric times through the Bronze and Iron Ages, with the earliest substantial occupation linked to the Edomites. From the 4th century BCE, Petra emerged as the Nabataean capital, leveraging its strategic position on caravan trade routes. The Roman annexation in 106 CE introduced imperial administrative structures and architectural influences, while Byzantine occupation is attested by churches and Christianized monuments. Early Islamic presence is documented but diminished, with seismic events in 363 and 551 CE contributing to the city’s decline. The site’s sandstone monuments have suffered from natural erosion and earthquake damage, yet many façades and infrastructure elements remain preserved. European explorers first mapped Petra in the early 19th century, and systematic archaeological research continues under Jordanian and international auspices. Petra was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985, reflecting its outstanding cultural and historical significance.

History

Petra’s historical trajectory spans several millennia, illustrating its evolution from a modest settlement into a prominent capital and later a diminished town within changing regional powers. Initially inhabited by Semitic groups such as the Edomites, the site rose to prominence under the Nabataeans, who exploited its strategic location along key trade routes. The Roman annexation incorporated Petra into a vast imperial network, bringing administrative reforms and architectural developments. Byzantine and early Islamic periods saw continued, though reduced, occupation, with natural disasters and shifting trade patterns accelerating its decline. After fading from historical records during the medieval era, Petra was rediscovered in the 19th century, initiating modern archaeological inquiry.

Edomite Occupation and Early Settlement (c. 1200–6th century BCE)

The earliest confirmed inhabitants of the Petra region were the Edomites, a Semitic people who settled in the basin surrounding Petra from approximately 1200 BCE. Archaeological evidence, including dry stone wall dwellings and artifacts such as inscribed seals found on Umm el-Biyara mountain, attest to their presence. One notable seal bears the name “Qōs-Gabr,” likely an Edomite king from the 7th century BCE. The Edomites developed textile production, ceramics, and metalworking, and constructed defensive fortifications on rocky promontories to protect their territory from desert nomads. While biblical texts identify the Edomites as descendants of Esau and adversaries of the Israelites, modern archaeology distinguishes Petra from the biblical city of Sela, clarifying earlier conflations. The Edomite occupation established the initial settlement framework in the region but did not develop Petra as an urban center or major trade hub.

Nabataean Foundation and Expansion (6th century BCE–106 CE)

From the 6th century BCE, the Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe, assumed control of Petra, establishing it as their capital by the early 4th century BCE. The city’s prosperity derived from its strategic position on caravan routes connecting South Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and the Mediterranean, facilitating trade in luxury goods such as incense, spices, silk, ivory, pearls, and turquoise. Classical authors like Diodorus Siculus and Strabo describe the Nabataeans as wealthy nomads engaged in the spice trade, with Petra’s population estimated at up to 20,000 by the 4th century BCE. Archaeological remains from this period, including high-quality buildings and imported pottery such as Rhodian amphorae and Greek black-gloss ware, confirm extensive trade connections.

The Nabataeans successfully resisted Hellenistic and early Roman incursions, defeating Hasmonean and Seleucid forces under kings Obodas I and Arétas III, thereby expanding their kingdom to encompass Moab, Galaad, and Damascus. Under King Arétas IV (circa 9 BCE–40 CE), Petra reached its zenith, with population estimates ranging from 20,000 to 40,000. This era witnessed a cultural flourishing, marked by the construction of most monumental tombs and temples. The Nabataean religion centered on Arabian deities such as Dusares and a female triad comprising Uzza, Al-Lat, and Manat, alongside royal cults venerating deified kings like Obodas I. The city’s architecture and urban planning reflect a synthesis of indigenous Arabian traditions with Hellenistic and Egyptian artistic influences.

Roman Conquest and Administration (106–4th century CE)

In 106 CE, the Roman Empire annexed the Nabataean kingdom without recorded military conflict, establishing the province of Arabia Petraea. Petra was designated a metropolis within the province, though the capital was located at Bosra. The Roman governor Cornelius Palma oversaw the transition. The Romans constructed a 400-kilometer road network linking Bosra, Petra, and the Gulf of Aqaba, facilitating military campaigns against the Parthians. Emperor Hadrian visited Petra in 131 CE, renaming the city Petra Hadriana in his honor.

Although the emergence of maritime trade routes diminished Petra’s commercial dominance, the city experienced a period of prosperity during the Pax Romana, as evidenced by increased construction activity. Roman influence is apparent in urban planning, including the establishment of a straight colonnaded main street (cardo) and public buildings such as a theater carved partly from rock, accommodating between 3,000 and 8,500 spectators. Petra’s sophisticated water management system, comprising aqueducts, dams, cisterns, and channels, supplied an estimated 40 million liters of water daily, comparable to other Roman urban centers. The city functioned as a municipium, integrating Nabataean traditions within the Roman administrative framework and serving as a regional military and commercial hub.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–7th century CE)

Following Emperor Constantine’s establishment of Constantinople in 330 CE, Petra became part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Christianity spread throughout the city, with a bishopric established by the mid-4th century CE. Several large churches adorned with mosaics and imported stones were constructed, and some Nabataean monuments, such as the Deir, were converted into Christian religious sites. Christian symbols, including crosses, appear in tombs and on walls, marking the city’s religious transformation.

A major earthquake on May 19, 363 CE caused extensive damage to Petra’s infrastructure, including the theater and waterworks. The city never fully recovered, as declining trade and repeated seismic events, including another significant earthquake in 551 CE, contributed to its gradual depopulation. The last known historical references to Petra date from the late 5th or early 6th century CE, indicating a diminished but ongoing occupation during this period.

Medieval Period and Crusader Occupation (7th–13th century CE)

The Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE brought profound changes to the region, but Petra itself appears to have declined to a small village by this time, with limited population and economic activity. The social structure likely consisted of subsistence farmers or pastoralists. The Islamic conquest did not significantly revive the site, which lacked major urban functions.

During the Crusades, Petra briefly regained strategic importance as part of the barony of Al-Karak within the lordship of Oultrejordain. Crusader forces, including Baldwin I of Jerusalem, occupied the area and constructed fortifications such as the Al-Wu’ayrah and Al-Habis castles to control the region. The local population was small and probably engaged in agriculture or trade supporting the garrisons. Religious life reflected the Crusader Christian presence, though no major new ecclesiastical buildings at Petra itself are documented. Saladin recaptured the region in 1187 following the Battle of Hattin. Later medieval travelers, including a German pilgrim in 1217 and Sultan Baybars in 1276, mention Petra, but the site remained largely forgotten thereafter.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (19th century–present)

Petra was reintroduced to the Western world in 1812 by Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, who entered the site disguised as an Arab pilgrim. Subsequent European expeditions in the 19th and early 20th centuries produced detailed maps, drawings, and initial archaeological studies, often influenced by biblical archaeology. Early explorers such as William John Bankes and Léon de Laborde contributed to the site’s documentation.

From the late 19th century onward, systematic excavations by Jordanian and international teams uncovered major structures including the Great Temple complex, Qasr al-Bint temple, residential quarters, and extensive water management systems. Research on approximately 4,000 inscriptions has illuminated the Nabataean language and script, a variant of Aramaic with Arabic influences, often bilingual with Greek and Latin. Conservation efforts have been ongoing since the mid-20th century to protect Petra’s fragile sandstone monuments from erosion and tourism impact. Petra was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985 and designated one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in 2007, affirming its global cultural and historical significance.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Edomite Occupation and Early Settlement (c. 1200–6th century BCE)

During the Edomite period, the population consisted of Semitic-speaking groups settled in the basin surrounding Petra, though not within the protected sandstone cliffs. Social organization likely included local chieftains or kings, as suggested by inscribed seals naming rulers such as “Qōs-Gabr.” The Edomites engaged in textile production, ceramics, and metalworking, activities conducted at household or small workshop scales. Defensive fortifications on rocky outcrops indicate coordinated community efforts to protect against desert nomads. Daily life centered on simple dry stone dwellings with minimal interior decoration. The diet probably relied on locally cultivated cereals and pastoralism, consistent with regional subsistence patterns. Transport involved foot travel and pack animals, facilitating trade and communication with neighboring groups. Religious practices likely involved veneration of local deities, though specific cultic evidence at Petra is limited. The Edomite presence established the region’s initial settlement framework but did not develop Petra as an urban center or major trade node.

Nabataean Foundation and Expansion (6th century BCE–106 CE)

Under Nabataean control, Petra transformed from a peripheral settlement into a thriving capital city. The population was predominantly Nabataean Arabs, organized into a hierarchical society comprising royal elites, priests, merchants, artisans, and caravan operators. Inscriptions attest to rulers such as Obodas I and Arétas IV, reflecting centralized authority and religious leadership. The Nabataeans transitioned from nomadic tent settlements to permanent rock-cut dwellings featuring flat roofs, interior courtyards, and modest decoration consistent with Middle Eastern domestic architecture.

Economically, Petra flourished as a caravan trade center dealing in luxury goods such as incense, spices, and precious materials. Workshops produced fine ceramics and metal goods, while agriculture—supported by advanced water management—provided cereals, fruit, and wine. Archaeological remains of rock-cut wine presses and imported pottery such as Rhodian amphorae indicate both local production and extensive trade connections. Markets likely operated within the city, where residents purchased imported luxury items alongside local staples. Transport relied heavily on camel caravans navigating regional trade routes linking South Arabia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean.

Religious life centered on Arabian deities including Dusares and a female triad (Uzza, Al-Lat, Manat), with royal cults venerating deified kings. Sacred betyl stones marked worship sites, and monumental tomb facades combined indigenous and Hellenistic motifs. Petra’s civic role was that of a prosperous, independent capital controlling surrounding territories, with administrative and religious institutions supporting its regional dominance.

Roman Conquest and Administration (106–4th century CE)

Following the peaceful Roman annexation, Petra became a major city within the province of Arabia Petraea, though the provincial capital was at Bosra. The population diversified to include Roman officials, local Nabataeans, and possibly settlers from other parts of the empire. Civic administration incorporated Roman magistrates and governors, as suggested by inscriptions referencing officials such as duumviri. Social stratification persisted, with elites commissioning public buildings and private tombs.

Economic activities shifted as maritime trade routes reduced Petra’s caravan dominance, but the city maintained prosperity through local agriculture, crafts, and administrative functions. The urban layout featured Roman-style infrastructure: a colonnaded cardo, a large theater partly rock-carved, baths, and public spaces. Water management was highly sophisticated, with aqueducts, dams, and cisterns supplying millions of liters daily, supporting both urban needs and agriculture. Domestic interiors included mosaic floors and painted stucco, reflecting Roman aesthetic influences. Markets offered a range of goods, including imported Mediterranean products and local crafts. Transport combined traditional caravan routes with improved Roman roads facilitating military and commercial movement. Religious practices diversified, with continued worship of traditional deities alongside the introduction of Roman gods and imperial cults. Petra functioned as a municipium-level city, integrating Nabataean traditions within the Roman imperial framework and serving as a regional administrative and military center.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–7th century CE)

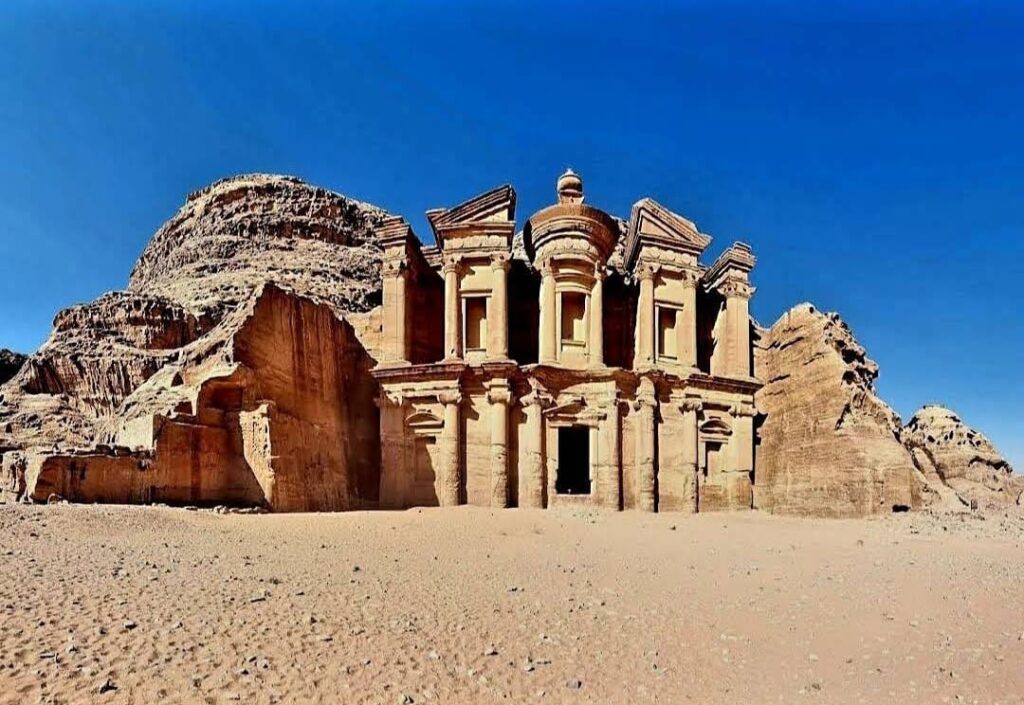

In late antiquity, Petra’s population declined but remained inhabited under Byzantine rule, with a growing Christian community led by a bishopric established by the mid-4th century CE. The social hierarchy included clergy, remaining local elites, and common residents. Christian churches with mosaic decoration were constructed, and some Nabataean monuments, such as the Deir, were converted into monasteries. Christian symbols appear in tombs and on walls, indicating religious transformation.

Economic activity contracted due to declining trade and repeated earthquake damage, notably the severe quake of 363 CE. Agriculture and craft production likely continued on a reduced scale, sustaining local needs. The urban fabric shows less monumental construction, with some reuse of earlier buildings. Markets and transport diminished accordingly. Religious life centered on Christianity, with liturgical practices and ecclesiastical governance shaping community organization. Petra’s civic role shifted from a prosperous trade capital to a diminished provincial town within the Byzantine Empire. Its administrative importance waned, but it retained ecclesiastical significance as a bishopric. The cumulative effects of natural disasters and economic changes led to gradual depopulation by the early 7th century.

Medieval Period and Crusader Occupation (7th–13th century CE)

By the early Islamic period, Petra had declined to a small village with limited population and economic activity. The social structure was minimal, likely composed of subsistence farmers or pastoralists. The Islamic conquest did not significantly revive the site, which lacked major urban functions.

During the Crusades, Petra briefly regained strategic importance as part of the barony of Al-Karak. Crusader occupation introduced military personnel and administrators, who constructed fortifications such as Al-Wu’ayrah and Al-Habis castles nearby. The local population was small and probably engaged in agriculture or trade supporting the garrisons. Religious life reflected the Crusader Christian presence, though no major new ecclesiastical buildings at Petra itself are documented. Transport and commerce were limited, with the site serving primarily as a military waypoint rather than a commercial center. After Saladin’s reconquest in 1187, Petra’s prominence diminished again, and it faded from historical records. Its civic role during this period was marginal, focused on military control rather than urban or economic development.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (19th century–present)

The 19th-century rediscovery of Petra reintroduced the site to scholarly and public attention, initiating a new phase of cultural and scientific significance. While no permanent population lived within the ancient city ruins, local Bedouin communities, such as the Bedul, maintained traditional lifestyles in the surrounding region, engaging in pastoralism and small-scale agriculture.

Archaeological excavations revealed detailed insights into past daily life, including domestic architecture, water management, and inscriptions illuminating social organization. Research uncovered evidence of diverse occupations, religious practices, and trade networks spanning millennia. Conservation efforts have aimed to preserve the fragile sandstone monuments and waterworks. Though not a living urban center today, Petra’s role as a cultural and historical landmark underscores its enduring importance in regional identity and heritage. The site functions as a focal point for understanding ancient urbanism, trade, and cultural exchange in southern Jordan and the wider Near East.

Remains

Architectural Features

Petra’s urban fabric is intimately shaped by its sandstone plateau and the surrounding narrow wadis, resulting in a cityscape dominated by rock-cut architecture integrated into cliffs and freestanding masonry structures. The city occupies a basin enclosed by steep cliffs, with natural gorges such as the Siq serving as principal access routes. Construction primarily employed local sandstone, either carved directly into rock faces or built using finely dressed ashlar masonry. The urban plan includes a central colonnaded street (cardo), religious complexes, residential quarters, and numerous funerary monuments. An extensive water management system, comprising dams, cisterns, aqueducts, and channels, is distributed throughout the site to capture and regulate seasonal water flows and spring sources.

Petra’s architecture reflects successive phases of development from its Nabataean foundation in the 6th century BCE through Roman annexation in 106 CE and Byzantine occupation. The Nabataean period is characterized by monumental rock-cut tombs and temples with elaborate façades. Roman influence introduced formal urban elements such as paved streets and a large theater. Later periods saw Christian adaptations of earlier structures and the construction of Crusader fortifications. Many buildings survive as façades or partial ruins, while some interiors and infrastructure remain preserved or have been excavated.

Key Buildings and Structures

The Siq

The Siq is a natural and partly carved rock fissure that served as Petra’s main entrance. It extends approximately 1,200 meters in length, with widths ranging from 3 to 12 meters and heights reaching up to 80 meters. The path was paved with stone slabs in antiquity, some of which remain in situ. Nabataean water channels run alongside the Siq, fed by springs outside the city. The rock walls bear numerous Nabataean carvings, predominantly depicting deities, with niches and shrines positioned near water channels. Notable features include the Sabinus niches, named after a Greek inscription honoring Nabataean gods, and reliefs of camels and caravan leaders symbolizing the wealth derived from trade.

The Khazneh (The Treasury)

Constructed in the 1st century CE, likely during the reign of King Arétas IV, the Khazneh is Petra’s most iconic rock-cut façade. It measures approximately 25 meters wide and 39 meters high, carved from sandstone. The two-story façade features six columns on the lower level standing on a platform with a central staircase. The lower columns reach about 12 meters, the upper ones approximately 9 meters, and a 3.5-meter urn crowns the top. The design combines Egyptian, Hellenistic, and Nabataean elements with high symmetry. Excavations have confirmed the Khazneh functioned as a royal tomb, with burial chambers beneath the courtyard preserved under a metal grate. The interior comprises a central chamber accessed by stairs and two side chambers, one containing a western tomb. Small holes on the exterior likely held scaffolding during carving, and a drainage channel at the top prevents water damage.

The Deir (The Monastery)

The Deir is a monumental rock-cut façade approximately 50 meters wide and 50 meters high, situated on a plateau about a 45-minute walk from Petra’s center. Built in the first half of the 1st century CE, it likely served as a Nabataean oratory dedicated to the deified King Obodas I. During the Byzantine period, the Deir was converted into a Christian monastery, as evidenced by crosses carved inside the lower chamber of the façade. The forecourt in front of the Deir was paved, and the structure retains much of its original rock-cut form.

Qasr al-Bint

Qasr al-Bint is one of Petra’s principal temples, constructed of sandstone and standing about 23 meters high. It is one of the few freestanding buildings rather than rock-cut, located at the end of a large paved esplanade with a long colonnade. The temple dates to the Nabataean period and was embellished during the Roman era. It features juniper beams arranged in an anti-seismic system. The structure suffered partial destruction, likely from the 363 CE earthquake. The temple housed a statue of the idol Dusares on a platform accessible by two staircases, with evidence of worship of other deities. Excavations uncovered remains of an earlier temple beneath Qasr al-Bint, possibly destroyed by an earthquake.

Temple of the Winged Lions

Dating to the 1st century CE, the Temple of the Winged Lions is a Nabataean religious complex dedicated to the goddess Al-Uzza. It includes a long ascending staircase leading to a grand entrance flanked by columns. The interior worship hall contains an elevated podium, likely supporting a statue of Al-Uzza, with priests and worshippers arranged around it. The temple’s name derives from lion motifs crowning the Corinthian capitals of the surrounding columns. Walls were decorated with floral and figurative motifs, and small niches around the podium probably held offerings or idols. The temple was destroyed and abandoned following the 363 CE earthquake.

The Roman Theatre

Constructed in the 1st century CE, the Roman Theatre is partly carved from rock and partly built with masonry. It features a semi-circular orchestra and three tiers of crescent-shaped seating. The seating area is divided horizontally into three sections and vertically by stairways into five or six parts. The stage wall has been destroyed. Archaeological excavations began in 1961 under American and Jordanian cooperation. The theatre’s remains include the seating and orchestra, though some structural elements are fragmentary.

Byzantine Church (North of the Colonnaded Street)

This large church, built in the 5th century CE north of Petra’s main colonnaded street, was richly decorated with mosaics and tesserae made of glass and stone, some covered with gold leaf. The decorative style combines Greco-Roman elements with local Petra-inspired motifs of plants and animals. The church was damaged by fire at the end of the 5th century, which destroyed marble elements and damaged over 140 papyri found in an adjacent chamber.

The Soldier’s Tomb Complex (Wadi al-Farasah)

Excavations since 2000 have uncovered a funerary complex dating to the late 1st century CE, just before Roman annexation. The complex includes the Soldier’s Tomb and a banquet hall (triclinium), both rock-cut on opposite sides of the wadi and connected by a peristyle. Additional buildings, including a porch and structures with hypocaust heating systems (underfloor heating), suggest possible residential use, which is unusual in funerary contexts.

The Great Temple (Grand Temple)

Located on the southern side of the main colonnaded street (cardo), the Great Temple is a large monumental complex. It includes a main entrance connected to the street, a lower sacred courtyard flanked by two semi-circular buildings, wide staircases leading to an upper sacred courtyard, and the temple or holy of holies above. The complex reflects the urban and religious architecture of Petra’s peak periods.

The Altar (Al-Madhbah)

Situated on a mountain massif accessible by stairs from the theatre, the Altar (Al-Madhbah) area was originally of Edomite origin and later reused by the Nabataeans. The site includes a central courtyard surrounded on three sides by seating. Two rock-carved obelisks stand nearby, believed to symbolize the chief Nabataean god Dushara and his consort Al-Uzza. The area contains remains of walls and a tower with Edomite foundations. Two altars are present: a rectangular one possibly used for circumambulation and a circular one likely for blood or wine offerings. A small water reservoir is also part of the complex. During the Crusader period, the site served as a link between the fortresses of Al-Wu’ayrah and Al-Habis and was used for sacrificial functions.

The Court (The Jar Tomb)

Located opposite the Nabataean theatre, the Jar Tomb features a façade approximately 16 meters wide and 26 meters high. It consists of two stories with walls supporting arches below the burial hall. The burial hall is a square room about 19 meters long, with burial chambers at the rear. The tomb was converted into a church in 447 CE, as attested by a Greek inscription on the rear left wall.

The Fortress Al-Wu’ayrah

Constructed during the Crusader period, the fortress Al-Wu’ayrah served as a military stronghold and religious site. It includes a tower and defensive walls. Archaeological evidence indicates the fortress was used for animal sacrifices. It is located near the Wadi al-Muhafara and connected to the Altar (Al-Madhbah) by processional routes.

The Fortress Al-Habis

Another Crusader fortress near Petra, Al-Habis functioned as a military and religious site. It is connected to the Altar (Al-Madhbah) by processional routes. The fortress includes defensive walls and structural remains consistent with Crusader military architecture.

The Garden Temple (House of Dorotheos)

The Garden Temple, also known as the House of Dorotheos, is a villa with a peristyle courtyard located near the Soldier’s Tomb complex. Excavations suggest a residential function. The site is associated with a nearby cistern, indicating water management for domestic use.

Other Tombs and Funerary Monuments

Petra contains numerous rock-cut tombs with elaborate façades, including the Obelisk Tomb, Urn Tomb, Corinthian Tomb, Palace Tomb, Sextius Florentinus Tomb, Turkmaniyeh Tomb, and Silk Tomb. Many tombs have multiple burial chambers and rich decorative elements. Some were converted into churches during the Byzantine period, as indicated by crosses carved on their façades.

The Colonnaded Street (Cardo)

The main paved street runs east-west along the south bank of Wadi Musa. It is approximately 6 meters wide and lined with one- to two-story buildings featuring porticoes with columns on both sides. A southern stairway leads to an open square known as the “market,” which served as the commercial heart from the 3rd century BCE through the Byzantine period. The street was rebuilt by the Romans after their annexation in 106 CE.

The Street of Facades

Located near the Khazneh where the Siq widens into an open area, the Street of Facades is flanked by numerous Nabataean tomb façades. These are decorated with merlons, cornices, and inverted stair motifs. Some façades have suffered damage from natural erosion. The tombs likely belonged to high-ranking officials or princes.

Water Management Infrastructure

Petra’s water system includes five hydraulic dams, open reservoirs, and approximately 200 cisterns, many situated on Umm el-Biyara (“Mother of Cisterns”) mountain. Two aqueducts carry water from the Siq area: one is an open channel collecting runoff from rock walls, plastered for waterproofing; the other is a closed system of terracotta or ceramic pipes with a gentle slope. The system supplied an estimated 40 million liters of water daily. Water management was centrally administered, with maintenance and cleaning overseen by authorities. The system supported domestic use, irrigation of gardens, and livestock.

Other Remains

Additional remains include the Monastery (Deir), used as a Christian monastery in the Byzantine period, and the Soldier’s Tomb complex, which contains hypocaust heating remains suggesting possible residential use. The Byzantine church north of the colonnaded street is richly decorated with mosaics and imported stones. The Altar (Al-Madhbah) massif includes Edomite foundations reused by Nabataeans. The Crusader fortresses Al-Wu’ayrah and Al-Habis are located nearby. Numerous rock-cut tombs and funerary monuments with elaborate façades are scattered throughout Petra. Remains of a large city wall survive in fragments, protecting the northern and southern flanks. The original large arch over the Siq entrance, about 16 meters high, has collapsed due to erosion and earthquakes, with only traces remaining. Surface traces of ancient dwellings with dry stone walls are found on Umm el-Biyara mountain. Approximately 4,000 inscriptions carved on rocks, mostly signatures of pre-Islamic pilgrims, are present. Archaeological evidence of pottery workshops, metalworking, and trade activities has also been documented.

Preservation and Current Status

Many of Petra’s rock-cut façades and masonry structures survive, though sandstone weathering and seismic damage have affected numerous surfaces. The Khazneh and Deir façades remain largely intact, while other tombs and temples show varying degrees of erosion and collapse. The Roman theatre’s seating and orchestra are partially preserved, but the stage wall is destroyed. The Byzantine church north of the colonnaded street retains mosaic decoration, though fire damage has affected some elements.

Restoration and conservation efforts have been ongoing since the mid-20th century, led by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities and international teams. Some structures have been stabilized or partially restored using original materials, while others remain in situ to preserve their archaeological integrity. Water management features are maintained to prevent further deterioration. Environmental threats include sandstone erosion and seismic activity. Excavations continue to reveal new features and monuments.

Unexcavated Areas

Only about 6% of Petra has been excavated as of 2020. Several districts and structures remain unexcavated or poorly studied. Surface surveys and aerial photography have identified subterranean structures and potential urban features within the basin and surrounding plateaus. Future excavations are planned but are limited by conservation policies and the need to protect fragile sandstone monuments. Some areas are accessible only through surface mapping and geophysical studies, with ongoing research aimed at expanding knowledge of Petra’s urban and religious landscape.