Bulla Regia: An Archaeological Site of Roman and Numidian Heritage in Tunisia

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Tunisia

Civilization: Byzantine, Phoenician, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Archaeological Site of Bulla Regia is situated near the contemporary town of Jendouba in northwestern Tunisia, occupying a strategic position on an elevated plateau within the Tell Atlas mountain range. This inland location, removed from the Mediterranean coast, benefits from a Mediterranean climate and fertile soils characteristic of the Medjerda River valley. The topography provided natural defensive advantages and access to vital water resources, facilitating sustained agricultural activity and settlement continuity.

Established initially during the Numidian period in the 3rd century BCE, Bulla Regia developed through successive cultural and political phases, notably under Roman rule from the 1st century BCE onward. The site expanded significantly during the Roman Imperial era, particularly in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, reflecting its role as a municipium and later colonia. Archaeological evidence indicates a decline in occupation during late antiquity and the early Byzantine period, with eventual abandonment in the early medieval era. The site’s partial burial and robust construction techniques have contributed to the preservation of its architectural remains.

Systematic archaeological investigations commenced in the early 20th century, uncovering extensive subterranean residential complexes and public buildings. Conservation efforts by Tunisian heritage authorities have aimed to stabilize the ruins and facilitate scholarly research, while controlled access supports ongoing excavation and study. Bulla Regia’s landscape and urban fabric provide valuable insights into adaptive architectural strategies and regional settlement patterns in North Africa.

History

Bulla Regia’s historical development exemplifies the complex interplay of indigenous, Punic, Numidian, Roman, and Byzantine influences in North Africa. Originating as a Berber settlement, the site evolved into a regional center with political, economic, and religious significance, particularly during the Numidian kingdom and Roman imperial periods. Its inland location within the fertile Medjerda valley positioned it as a nexus of agricultural production and administrative authority. Although its prominence diminished in late antiquity, archaeological and epigraphic evidence attest to continued occupation into the early Islamic era.

Pre-Punic and Punic Period (Before 2nd century BCE)

Prior to Carthaginian dominance, Bulla Regia was established as a Berber settlement, as demonstrated by a well-preserved megalithic necropolis and Neo-Punic tombs containing characteristic funerary vases. The discovery of Greek pottery dating to the 4th century BCE attests to early engagement with Mediterranean trade networks. By the 3rd century BCE, the city came under Carthaginian influence, confirmed by inscriptions invoking the god Ba’al Hammon and the presence of a temple dedicated to the goddess Tanit. A hoard of Carthaginian electrum and silver coins, dated circa 230 BCE and found within the House of the Hunt, reflects the city’s integration into Carthage’s economic sphere.

During this period, Bulla Regia functioned as a regional center combining indigenous Berber traditions with Punic religious and economic practices. The settlement’s location facilitated agricultural production and trade, linking inland communities with coastal Carthaginian markets. Religious life centered on Punic deities, as evidenced by epigraphic and architectural remains, while burial customs followed established Punic rites.

Numidian Royal Capital (156 BCE – 1st century BCE)

Following the decline of Carthaginian power, Bulla Regia was designated as a secondary capital of the Numidian kingdom under King Massinissa in 156 BCE. This period marked a significant urban transformation, with the introduction of a Hellenistic orthogonal street grid supplanting earlier irregular layouts. Defensive walls constructed of large masonry blocks, some extant today, delineated the city’s boundaries. The political importance of Bulla Regia is underscored by the execution of Hiarbas, son of Massinissa, by Pompey in 81 BCE, an event recorded in Roman historical sources.

As a royal seat, Bulla Regia served both political and economic functions within the Numidian realm. The population comprised Numidian elites aligned with Rome alongside indigenous Berber communities. Agricultural production, particularly grain and olives, underpinned the local economy, while craft activities and trade expanded in response to the city’s strategic inland position. Religious practices maintained Punic traditions, with temples dedicated to Tanit and Ba’al Hammon continuing in use. The city’s urban planning and fortifications reflect increasing centralization and adaptation to regional geopolitical dynamics.

Roman Republican and Early Imperial Period (46 BCE – 2nd century CE)

After Julius Caesar’s victory at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BCE, Bulla Regia was incorporated into the Roman province of Africa. Unlike neighboring settlements granted veteran colonies, Bulla Regia retained the status of a free city, preserving its territorial integrity and local political institutions. Under the Flavian dynasty, likely initiated by Emperor Vespasian, the city was elevated to municipium status, conferring Latin rights but not full Roman citizenship. Subsequently, during Emperor Hadrian’s reign, it attained the rank of colonia, named Colonia Aelia Hadriana Augusta Bulla Regia, granting full Roman citizenship and adopting Roman-style political structures.

Romanization advanced through the adoption of Latin language, Roman personal names (tria nomina), and civic institutions modeled on Italian precedents. Prominent local families, including the Marcii and Aradii, accrued wealth through grain and olive oil production and trade, achieving senatorial rank by the early 3rd century CE. The city’s population remained modest, estimated at a few thousand inhabitants, yet its prosperity is reflected in monumental architecture and elite patronage. Religious practices diversified, incorporating Roman cults alongside residual Punic elements.

Roman Imperial Period (2nd – 4th century CE)

The 2nd and 3rd centuries CE represent the apex of Bulla Regia’s urban and cultural development. The city’s elite constructed distinctive subterranean houses featuring underground floors that replicated the upper-level plans, an architectural innovation unique in Roman North Africa. The House of the Hunt, with its expansive peristyle courtyard supported by Corinthian columns and an underground triclinium, exemplifies this design. The house also includes an early example of separated toilet and bath facilities, indicating advanced sanitary arrangements. Similar subterranean layouts are found in the House of the Fisherman and House of Amphitrite, which incorporate small courtyards or light wells for ventilation and illumination.

Mosaics from this period, dating broadly from the 2nd to early 4th century CE, depict mythological figures such as Venus (formerly misidentified as Amphitrite), cupids, and hunting scenes, demonstrating high artistic craftsmanship despite the anonymity of mosaicists. Public infrastructure expanded with the construction or enhancement of a theater (initially built under Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus and renovated in the 4th century), a forum complex featuring a temple dedicated to Apollo, and a market sponsored by the Aradii family, reflecting the importance of grain commerce. The Julia Memmia baths, enlarged in the late 4th century, exhibit hypocaust heating and marble decoration, underscoring continued investment in public amenities. A private basilica within the House of the Hunt illustrates the integration of religious architecture into domestic settings during this period.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (4th – 7th century CE)

By the late 4th century, Bulla Regia had undergone full Christianization, with a bishopric attested by 256 CE. Christian iconography appears in mosaics, including peacocks symbolizing resurrection, often juxtaposed with older pagan motifs such as the kantharos jar, reinterpreted within Christian symbolism. The presence of a private basilica within the House of the Hunt indicates the fusion of domestic and ecclesiastical architecture. St. Augustine’s recorded visit and critique of local impiety reflect active theological discourse. The city participated in the 411 CE Conference of Carthage, addressing the Donatist schism.

Under Vandal rule, Arian persecution resulted in the massacre of Catholics within the city’s basilica. Byzantine administration saw a gradual decline in urban vitality, with architectural modifications evidencing aristocratic expansion at the expense of public spaces, such as the connection of insulae via the “Fisherman’s Room.” Byzantine coins from the 7th century found in the House of the Treasure confirm continued occupation, albeit diminished. Archaeological finds of Aghlabid and Fatimid glazed ceramics in the baths suggest some continuity of habitation into the early Islamic period, challenging earlier assumptions of abrupt abandonment.

Early Islamic Period and Abandonment (8th – 10th century CE)

Material culture from the early Islamic period, including Aghlabid and Fatimid glazed ceramics recovered from the bath complexes, indicates limited but persistent occupation of Bulla Regia into the 9th and 10th centuries CE. However, the city’s urban functions and population were significantly reduced, with no evidence of substantial new construction or administrative activity. The remaining inhabitants likely engaged in small-scale agriculture and localized trade, adapting to the shifting political and economic landscape of early medieval North Africa.

Religious life transitioned to Islam, though direct archaeological evidence for Islamic institutions at the site is sparse. The absence of major mosques or Islamic public buildings suggests a diminished urban community, possibly oriented around rural or semi-urban households. The site was ultimately abandoned by the 10th century, with causes potentially linked to economic decline, political instability, and changing settlement patterns in the region.

Modern Rediscovery and Excavation (19th century – present)

Bulla Regia remained largely forgotten until European explorers documented the site beginning in 1853. Initial excavations at the close of the 19th century uncovered tombs and basilicas, prompting systematic archaeological investigations from 1906 onward. Early 20th-century work focused on major structures such as the large baths (1909–1924) and the temple of Apollo (circa 1910). Mid-century excavations revealed the forum and surrounding porticoes, though some early efforts lacked rigorous scientific methodology.

From 1972, Franco-Tunisian archaeological teams resumed methodical excavations, publishing detailed findings and concentrating on previously uncovered structures. The site is currently protected within an archaeological park, although significant areas, including the amphitheater, remain unexcavated. Numerous mosaics and statues from Bulla Regia are preserved in the National Bardo Museum in Tunis, including notable works such as the “Deliverance of Andromeda by Perseus” and statues of Roman emperors and deities. The dispersal and incomplete publication of early finds have complicated comprehensive understanding, underscoring the need for ongoing research and conservation.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Numidian and Punic Period (Before 2nd century BCE)

During its earliest occupation, Bulla Regia was inhabited predominantly by indigenous Berber populations, as evidenced by megalithic tombs and Neo-Punic funerary artifacts. The presence of 4th-century BCE Greek pottery indicates active participation in Mediterranean trade networks, facilitating the exchange of ceramics and luxury goods. Subsistence likely combined mixed agriculture with trade connections to Carthage and other coastal centers. Social organization was clan-based, with religious practices centered on Punic deities such as Ba’al Hammon and Tanit, worshipped in temples confirmed by inscriptions and architectural remains.

Daily life included established Punic funerary customs, and diet probably consisted of cereals, olives, and freshwater fish. Clothing styles reflected regional Berber and Punic traditions, likely comprising simple tunics and cloaks adapted to the Mediterranean climate. Although domestic architecture from this period remains poorly documented, burial contexts suggest communal and familial living arrangements. The city functioned as a regional hub under Carthaginian influence, integrating local agricultural production with broader economic networks while maintaining a distinct Berber cultural identity.

Numidian Royal Capital (156 BCE – 1st century BCE)

As the secondary capital of the Numidian kingdom under King Massinissa, Bulla Regia experienced significant urban and social transformation. The population included Numidian elites allied with Rome alongside indigenous Berber communities. The introduction of a Hellenistic orthogonal street grid and substantial defensive walls reflects increased political centralization and urban organization. Social hierarchy encompassed royal family members, military officials, artisans, and farmers, with inscriptions attesting to magistrates and local administrators.

Economic life centered on agriculture, particularly grain and olive cultivation, supporting local consumption and tribute obligations. Craft production and trade expanded, facilitated by the city’s strategic inland location in the fertile Medjerda valley. Dietary staples included bread, olives, and wine. Clothing styles began to incorporate Hellenistic influences, such as tunics and cloaks, as suggested by regional parallels. Houses were arranged along the new street grid, though detailed domestic layouts remain under-explored. Religious life continued Punic traditions, with temples dedicated to Tanit and Ba’al Hammon, while political events like the execution of Hiarbas by Pompey highlight the city’s role in regional power dynamics.

Roman Republican and Early Imperial Period (46 BCE – 2nd century CE)

Following Roman annexation, Bulla Regia retained a distinct civic identity as a free city before its elevation to municipium and later colonia status. The population became increasingly Romanized, adopting Latin language, Roman personal names, and political institutions modeled on Italian examples. Elite families such as the Marcii and Aradii emerged as prominent landowners and senators, reflecting a stratified society comprising wealthy aristocrats, artisans, and rural laborers.

Agriculture remained the economic foundation, focusing on grain and olive oil production for local use and export. Workshops and small-scale manufacturing likely operated within the city, though no large industrial zones have been documented. Diet included cereals, olives, fish, and wine, consistent with Roman North African patterns. Clothing followed Roman fashions, with tunics, togas for elites, and sandals common. Residential architecture evolved to include houses with open courtyards and elaborate decoration. Public amenities such as forums and temples supported civic life, with inscriptions referencing magistrates like duumviri. Markets supplied imported goods, transported via regional roads and river routes. Religious practices diversified, incorporating Roman cults alongside lingering Punic elements, as Bulla Regia integrated local elites into imperial structures while maintaining agricultural productivity.

Roman Imperial Period (2nd – 4th century CE)

The 2nd and 3rd centuries CE marked Bulla Regia’s architectural and cultural zenith. The population included Romanized elites, freedmen, artisans, and agricultural workers. Patriarchal households were headed by male landowners, with women managing domestic affairs and religious rites. The elite commissioned distinctive subterranean houses with underground floors replicating upper plans, providing cooler living spaces adapted to the local climate. These residences featured peristyles, private baths with early sanitary designs, and richly decorated mosaic floors depicting mythological and hunting scenes.

Economic activities remained anchored in agriculture, supplemented by trade in grain and olive oil. The Aradii family’s sponsorship of markets and public buildings illustrates elite patronage and commercial vitality. Local workshops produced mosaics, pottery, and textiles, while public baths and theaters supported social and leisure activities. Markets offered both local produce and imported goods, transported via well-maintained roads connecting Bulla Regia to broader imperial networks. Religious life transitioned toward Christianity by the late 3rd century, with early private basilicas integrated into domestic architecture. Pagan and Christian iconography coexisted in mosaics, reflecting syncretism. Civic administration included municipal councils and magistrates, with inscriptions confirming local governance aligned with Roman legal frameworks. Bulla Regia functioned as a prosperous colonia, balancing agricultural wealth, urban sophistication, and religious transformation.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (4th – 7th century CE)

By late antiquity, Bulla Regia’s population had become predominantly Christian, with a bishopric established by the mid-3rd century CE. Social life centered on ecclesiastical institutions alongside traditional civic structures. Christian iconography, such as peacock mosaics symbolizing resurrection, adorned domestic and religious spaces, while older pagan motifs persisted in transformed symbolic contexts. The city’s elite maintained large private homes, some expanded at the expense of public spaces, indicating shifting social priorities.

Economic activity declined but remained focused on agriculture and local trade. Byzantine coins and architectural modifications suggest continued occupation under imperial administration, though on a reduced scale. The city endured religious conflicts, including Arian persecution under the Vandals and participation in regional councils addressing doctrinal disputes. Daily life incorporated Christian rituals and festivals, with clergy playing prominent roles in community leadership. Educational activities likely included catechesis and scriptural instruction, consistent with contemporary North African Christian centers. Transportation relied on regional roads and animal caravans, supporting diminished but ongoing commerce. Bulla Regia’s civic role contracted, functioning primarily as a bishopric and local agricultural center within the Byzantine province.

Early Islamic Period and Abandonment (8th – 10th century CE)

Archaeological evidence of Aghlabid and Fatimid glazed ceramics indicates limited continuity of occupation into the early Islamic period, though urban functions and population were significantly reduced. The city no longer served as a major administrative or commercial hub, with no substantial new construction documented. Remaining inhabitants likely engaged in small-scale agriculture and local trade, adapting to changing political and economic conditions.

Religious life shifted to Islam, though direct evidence at Bulla Regia is sparse. The absence of major mosques or Islamic public buildings suggests a diminished urban community, possibly centered on rural or semi-urban households. Transport and commerce were limited, reflecting broader regional realignments in trade routes and governance. Ultimately, the site was abandoned by the 10th century, possibly due to economic decline, political instability, and shifting settlement patterns. Bulla Regia’s long history as a regional center concluded, leaving behind a rich archaeological record documenting its complex evolution.

Remains

Architectural Features

Bulla Regia’s archaeological remains are distinguished by their adaptation to the local topography and climate, notably through the construction of subterranean residential floors. The city occupies an elevated plateau, with urban development reflecting a transition from irregular early layouts to a Hellenistic orthogonal street grid established during the Numidian period. Defensive walls constructed of large ashlar masonry blocks, dating to the 2nd century BCE, partially survive and delineate the ancient city boundaries. Building materials include local stone and imported architectural elements, such as columns from Simitthus adorning the House of the Hunt’s main courtyard.

Residential insulae north of the Forum contain richly decorated houses with underground floors built on deep foundations rather than simple excavations. These subterranean levels were ventilated and illuminated by open courtyards or light wells, an architectural innovation unique in Roman North Africa, likely intended to moderate summer temperatures. Public structures include vaulted rooms, peristyles, and private baths with early sanitary features. Byzantine modifications reflect a contraction of public spaces in favor of expanded aristocratic residences.

Key Buildings and Structures

House of the Hunt

Dating broadly from the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE, the House of the Hunt is a prominent residential complex located in an insula north of the Forum. Named after a mosaic depicting hunting scenes, the house features a peristyle courtyard supported by Corinthian columns imported from Simitthus. Unlike comparable houses at Utica, access to the lower floor is via steps descending from the courtyard. The subterranean level was constructed on deep foundations and received air and light through an open courtyard, likely providing cooler conditions during summer months.

The house contains an early example of a separated bath and toilet facility, with the toilet positioned behind a curved wall, representing a “double W.C.” arrangement. Archaeological evidence indicates that the lower floor was later repurposed as a necropolis. Adjacent to this house is the New House of the Hunt, which shares architectural features and mosaic themes, though some mosaics have suffered damage due to necropolis use.

New House of the Hunt

Adjoining the House of the Hunt, this residence exhibits similar architectural characteristics and mosaic subjects. Its principal mosaic portrays the owner engaged in hunting, followed by servants, framed by an inhabited scroll motif including a hare. The mosaics date from the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE. Some mosaics have been damaged due to the lower floor’s later use as a burial site.

House of the Fisherman

Structurally akin to the House of the Hunt but with a smaller courtyard, the House of the Fisherman also includes a subterranean floor illuminated by the courtyard, which contains a fountain. The lower floor plan is smaller than the ground floor. Named after mosaics depicting fishing scenes, the house dates to the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE.

House of Amphitrite

Constructed in the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE, the House of Amphitrite features a lower floor with a small inner courtyard open on one side. Light enters primarily through windows at the top of a high corridor leading to a triclinium (dining room), two small bedrooms, and a kitchen. Additional ventilation is provided by wells in the corridor. The house is named after a mosaic originally thought to depict Amphitrite but now identified as the Toilet of Venus, showing two cupids crowning Venus. The mosaic’s eyes were originally set with gems, now missing.

The lower floor comprises three rooms receiving air and light from the corridor. The Toilet of Venus motif was popular and persisted into the Christian period, sometimes replaced by Christian symbols. The mosaic style indicates high artistic skill, though mosaic makers remained anonymous. The house underwent refurbishment during the Christian era.

House of the Treasure

Similar in construction to the House of Amphitrite, the House of the Treasure’s lower floor includes three rooms with light and air access from a corridor. The vaults of these rooms have collapsed. The house is named after a coffer containing silver coins found on site, now housed in the Museum of Bardo in Tunis. Occupied until the Arab invasion in the 7th century CE, the house was refurbished following the city’s Christianization.

House of the Peacock

Located adjacent to the House of the Hunt, the House of the Peacock was inhabited until the 7th century CE and refurbished during the Christian period. Its mosaics combine Christian symbols, such as peacocks representing Resurrection, with older pagan motifs like the kantharos jar. Some mosaics suffered damage due to the lower floor’s use as a necropolis.

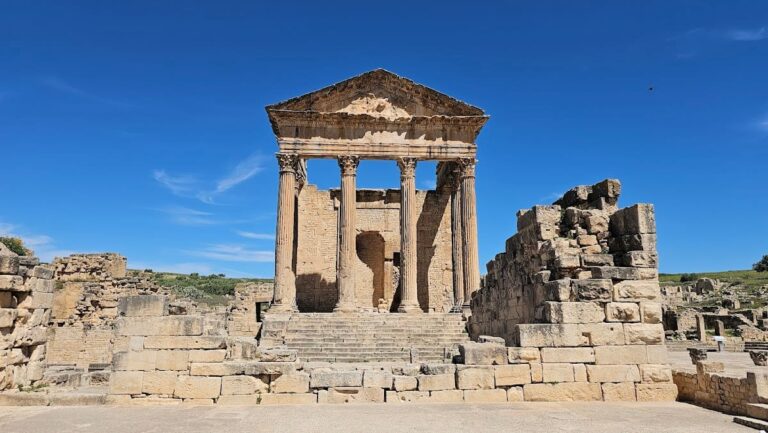

Forum and Temple of Apollo

The forum complex includes a temple dedicated to Apollo, constructed during the Roman Imperial period. Excavations have revealed porticoes surrounding the forum, with some structural elements preserved. Statues recovered from the temple are now housed in the Museum of Bardo. The forum and temple date primarily to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, with modifications in later periods.

Public Baths (Julia Memmia Baths)

The Julia Memmia baths were expanded in the late 4th century CE. The complex includes caldarium (hot bath) and frigidarium (cold bath) rooms, with evidence of early sanitary innovations such as separated latrines. The baths remained in use into late antiquity and show signs of refurbishment during the Christian period. Archaeological remains include vaulted rooms and hypocaust (underfloor heating) systems.

Theater

The city’s theater, constructed during the Roman Imperial period, retains partial remains of its seating area (cavea) and stage structures. The theater’s layout corresponds to typical Roman designs but is only partially excavated and preserved.

Defensive Walls and Gates

Defensive walls built of large masonry blocks date to the Numidian period (2nd century BCE). Portions of these walls and gates remain visible, marking the city’s boundaries. The walls were constructed with ashlar masonry and show evidence of repairs and modifications during later Roman and Byzantine periods.

Other Remains

Additional structures include residential insulae with subterranean floors, some featuring vaulted ceilings. Several houses contain mosaics broadly dated from the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE. Some mosaics and architectural elements have been damaged due to later reuse of underground spaces as necropolises. The site also contains funerary monuments and tombs, including a megalithic necropolis and Neo-Punic tombs from the pre-Punic and Punic periods.

Archaeological surveys have identified unexcavated areas, including an amphitheater and further residential quarters. Surface finds include columns, capitals, and fragments of statues. The site’s layout reflects a combination of civic, residential, and religious functions.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have uncovered numerous mosaics dating from the 2nd to early 4th centuries CE, depicting mythological, hunting, and fishing scenes. Notable mosaics originate from the House of the Hunt, House of the Fisherman, and House of Amphitrite. Christian iconography appears in late antique mosaics, such as peacocks symbolizing Resurrection.

Coins from various periods have been found, including a hoard of Carthaginian electrum and silver coins dated around 230 BCE in the House of the Hunt, and silver coins from the House of the Treasure now preserved in the Museum of Bardo. Byzantine coins from the 7th century CE confirm continued occupation into late antiquity.

Pottery includes locally produced wares and imported Greek ceramics from the 4th century BCE, indicating early Mediterranean trade connections. Inscriptions referencing deities such as Ba’al Hammon and dedications to Tanit have been recovered, primarily from the Punic period. Domestic artifacts such as lamps and cooking vessels have been found in residential contexts.

Religious artifacts include statues from the temple of Apollo and Christian basilicas within private houses, such as the basilica in the House of the Hunt. Funerary artifacts from necropolises include sarcophagi and grave goods consistent with Punic and Roman burial customs.

Preservation and Current Status

The subterranean houses of Bulla Regia are relatively well-preserved due to their partial burial and robust construction. Vaulted ceilings and peristyles survive in several houses, though some vaults, notably in the House of the Treasure, have collapsed. Mosaics remain in situ in many buildings but have suffered damage from later necropolis use and environmental exposure.

Conservation efforts by Tunisian heritage authorities focus on stabilizing structures and preventing further deterioration. Some areas have undergone partial restoration using original materials, while others are stabilized in situ without reconstruction. The Museum of Bardo in Tunis houses many mosaics, statues, and coins from Bulla Regia, contributing to their preservation.

Environmental threats include erosion and vegetation growth, while looting has affected some mosaics and artifacts, such as the stolen gems from the House of Amphitrite mosaic. Excavations continue under controlled conditions to balance research and preservation.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of Bulla Regia remain unexcavated, including the amphitheater and extensive residential districts beyond the insula of decorated houses. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains in these areas, but excavation is limited by conservation policies and modern land use.

Future archaeological work is planned to focus on these unexcavated zones, though progress depends on funding and preservation priorities. Some areas are intentionally left undisturbed to protect fragile remains and prevent damage from exposure.