Arta Castle: A Byzantine Fortress in Greece

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.kastra.eu

Country: Greece

Civilization: Byzantine, Ottoman

Remains: Military

History

Arta Castle stands on a hill at the northeastern edge of Arta, Greece, built by Byzantine and local rulers upon the ruins of the ancient town of Ambracia. Ambracia itself was abandoned after 31 BC when the nearby city of Nicopolis was established by Augustus. The castle’s first recorded mention dates to 1082, during a Norman siege that noted fortifications at the site.

In the early 13th century, Arta became the capital of the Despotate of Epirus, a Byzantine successor state, with the castle acting as its citadel. The main phase of construction is credited to Michael II Komnenos Doukas, who ruled Epirus from 1230 to around 1266, an attribution marked by a monogram found near the castle’s principal gate tower. Throughout the following centuries, the castle endured several sieges, including attacks by Charles II of Anjou in 1303 and Byzantine emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos between 1328 and 1341.

Control of Arta and its castle passed through various hands over time, reflecting the region’s turbulent history. After the Byzantine and local rulers, it came under Serbian and Albanian control, followed by Angevin, Ottoman, Venetian, and French rule. The Ottomans captured the castle in 1449, integrating it into their empire. During Ottoman administration, the fortress functioned as both a prison and the residence of the local governor, detaining notable Greek revolutionaries. The castle finally became part of the modern Greek state in 1881 following territorial changes in the region.

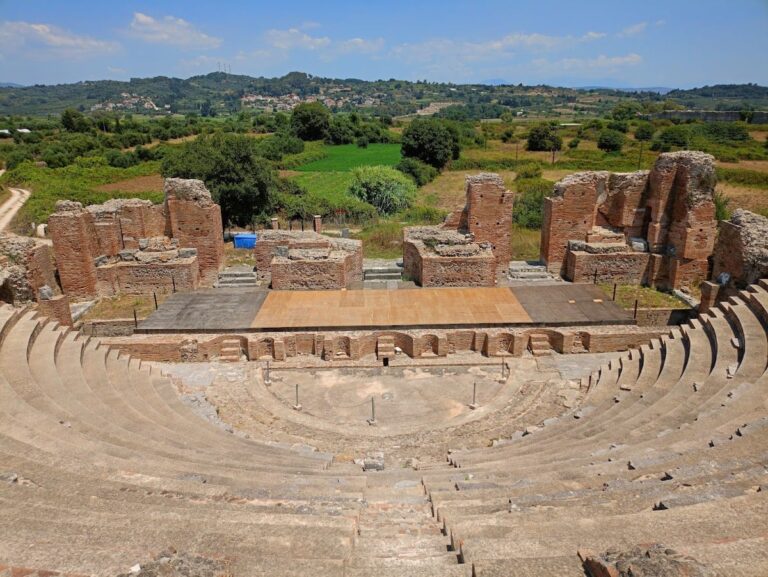

In the 20th century, a portion of the castle was repurposed to accommodate the Xenia hotel, indicative of adaptive reuse in the area. Starting in 1987, the castle incorporated an open-air theater that has since hosted cultural events. Extensive preservation and restoration work took place between 2011 and 2015, focusing on repairing structures and improving access within the site.

Remains

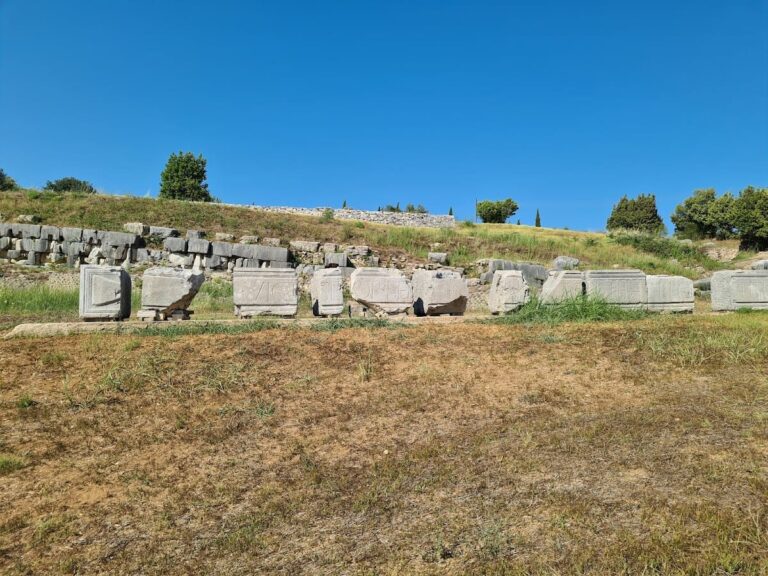

The castle occupies an irregular polygonal enclosure approximately 280 meters long, oriented northeast to southwest, and up to 175 meters wide. Its walls rise to about 10 meters in height and are roughly 2.5 meters thick. Notably, the eastern wall includes large, carefully cut stone blocks—ashlars—reused from the ancient city of Ambracia’s defensive wall, demonstrating continuity of construction materials across periods. The castle’s natural defenses are enhanced on the east side by steep cliffs and the Arachthos River, which in medieval times flowed closer to the walls than it does today.

Around the perimeter stand eighteen towers spaced roughly every 25 meters, varying in design from semi-circular and triangular to polygonal shapes. These towers provided vantage points and fortified positions along the defensive wall. The southwest corner encloses a smaller, inner section of the castle, often called the “inner castle.” Within this area, building remains have been linked to a 15th-century palace associated with the ruling Komnenos Doukas family, reflecting the castle’s role as a residence as well as a fortress.

The fortifications consist of two concentric walls on most sides. The inner wall, about 10 meters high, carries the main line of towers and remains largely intact today. An outer wall, lower at approximately 4 to 5 meters tall, once surrounded the inner defenses and included additional towers, but now survives mostly in fragments. During Ottoman and later Venetian control, modifications were added to adapt the fortress to artillery warfare. These changes include bastions and openings in the parapets and towers designed for cannons and firearms, altering the medieval character of the walls.

A tall clock tower was constructed and added to the walls in 1875, symbolizing a later phase of occupation and adaptation. Inside the castle, archaeological layers revealed a Byzantine church and structures thought to be the Despotate’s palace and its associated chapel. Unfortunately, much of these internal remains were destroyed or heavily damaged by the 1960s construction of the hotel that occupied part of the site. Despite these losses, the remaining walls and towers provide a visible record of the castle’s long and varied history.