Carteia: An Ancient Roman Colonia in Cádiz, Spain

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.juntadeandalucia.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Phoenician, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Carteia is situated within the contemporary municipality of San Roque in the province of Cádiz, Spain, occupying a low-lying coastal plateau on the northern shore of the Bay of Gibraltar. The site lies near the modern coastline, adjacent to estuarine marshlands formed by the Guadarranque River, which historically provided access to maritime routes. This strategic position near the Strait of Gibraltar, known in antiquity as the Pillars of Hercules, afforded control over the passage between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

Archaeological investigations have revealed continuous occupation at Carteia from the late first millennium BCE, beginning with Phoenician and indigenous settlements, followed by Punic cultural layers. Roman dominion was established after the Second Punic War, with documentary and epigraphic evidence confirming its status as a Roman colonia from 171 BCE. Numismatic finds and inscriptions attest to the persistence of municipal institutions through the Imperial period. Stratigraphic data indicate continued habitation into Late Antiquity, with a decline during the early medieval era. The site has been subject to scholarly attention since the eighteenth century, with systematic archaeological research commencing in the twentieth century, uncovering material culture that corroborates its historical significance.

Today, Carteia’s archaeological remains are protected under regional heritage legislation. The visible ruins include fortifications, public buildings, and domestic structures, which collectively illustrate the site’s long-term occupation and evolving urban character within the broader context of southern Iberian history.

History

Carteia’s historical trajectory reflects its transformation from a Phoenician maritime outpost into a Roman colonial city, followed by phases of occupation through Late Antiquity and the medieval period. Its location near the Strait of Gibraltar made it a focal point for maritime control and military engagements. Over time, the site experienced successive political dominions, including Carthaginian, Roman, Visigothic, Byzantine, and Islamic authorities, each contributing to its archaeological and historical record. The city’s prominence diminished after the medieval era, yet its ruins preserve a stratified narrative of these cultural transitions.

Phoenician Foundation and Punic Period (7th–3rd century BCE)

Carteia originated in the 7th century BCE as a Phoenician settlement established on the Cerro del Prado promontory overlooking the mouth of the Guadarranque River. This location was strategically selected to oversee the maritime corridor known as the Pillars of Hercules, controlling access between the Mediterranean and Atlantic. The initial settlement was modest in scale, situated on a river promontory surrounded by marshes and sandbanks, reflecting a typical Phoenician trading post.

By the 4th century BCE, under Carthaginian influence—particularly the Barcid family—the site expanded into a larger urban center. This phase incorporated Hellenistic urban planning principles and defensive architecture, including a well-preserved casemate wall constructed with squared ashlar blocks joined by mortise-and-tenon joints, characteristic of Punic-Hellenistic fortifications in Iberia. Carteia’s territory extended through a network of satellite sites positioned along key terrestrial and maritime routes, such as Monte de la Torre and Cerro de los Infantes, underscoring its role in regional control and trade during the Punic era.

Roman Conquest and Colonial Establishment (3rd–1st century BCE)

The Second Punic War (218–201 BCE) brought Carteia into the conflict between Rome and Carthage. In 206 BCE, two significant battles occurred near the site: a land engagement where Roman forces under Gaius Lucius Marcius Septimus defeated the Carthaginian commander Hannon, and a naval battle in which Gaius Laelius overcame the Carthaginian admiral Adherbal. These victories facilitated Roman ascendancy in southern Iberia.

Following the war, Rome captured Carteia around 190 BCE. In 171 BCE, the Roman Senate established Colonia Libertinorum Carteia, the first Latin colony founded outside Italy. This colony settled approximately 4,000 freedmen descended from Roman soldiers and local Hispanic women, granting them Latin Rights—a legal status conferring privileges between those of non-citizen provincials and full Roman citizens. Indigenous inhabitants were permitted to remain, and all residents acquired rights to intermarry with Roman citizens and engage in commerce, representing a notable legal innovation in Roman colonial policy.

Under Roman administration, Carteia developed into a prosperous urban center featuring a forum, temples, a theater, baths, and a mint. The city became a hub for the export of local wines, amphora production, and garum fish sauce manufacture. During the late Republic, Carteia was involved in civil conflicts; notably, in 46 BCE, a naval battle near the city saw Caesarian forces under Caius Didius defeat Pompeian opponents led by Publius Attius Varus.

Imperial Roman Period (1st century BCE–3rd century CE)

During the early Imperial period, Carteia flourished as a municipium within the Roman province of Baetica. Augustan-era urban renewal projects enhanced public amenities, including the reconstruction of the forum and residential domus. The city sustained its economic role as a port and production center, with continued manufacture of amphorae and garum fish sauce. Archaeological evidence documents a pottery production hiatus in the first half of the 1st century CE, likely caused by a tsunami event.

Public buildings such as the theater, baths with hypocaust heating, and fortified walls incorporating earlier Punic masonry remained in use. Numismatic evidence, including coins minted locally between 103 and 30 BCE, attests to active municipal governance. Over time, Christian influences began to emerge, foreshadowing religious transformations in subsequent centuries.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–6th centuries CE)

Carteia continued to be occupied during Late Antiquity, experiencing demographic continuity alongside cultural and religious transformation. The introduction of Christianity is evidenced by the foundations of an early Christian basilica near the forum and Christian burials within a Visigothic necropolis. Tombs from this period often reused materials from earlier Roman structures, reflecting adaptation amid continuity.

Economic activity diminished relative to earlier periods but remained sufficient to support local needs. Byzantine control during the 6th and 7th centuries CE incorporated Carteia into the province of Spania, as confirmed by archaeological remains. This period saw the maintenance of some urban functions and administrative integration into the Eastern Roman Empire, with religious life centered on Christianity and ecclesiastical authorities assuming civic prominence.

Islamic and Medieval Period (8th–14th centuries CE)

Following the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 CE, Carteia—referred to in Arabic sources as Qartayanna or Cartagena—contracted into a small village. Although no mosque remains have been excavated, historical sources attest to its existence, suggesting religious and cultural transformation under Islamic rule. The population likely comprised Muslim settlers alongside residual Christian and indigenous groups, with social organization governed by Islamic law.

Economic life during this period focused on subsistence agriculture, fishing, and limited trade. Domestic architecture adapted to Islamic styles, though archaeological evidence remains limited. The site’s strategic importance was renewed in the medieval era with the construction of the Torre de Cartagena, a watchtower and fortress erected in the early 13th century by the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada following the Almohad defeat at Navas de Tolosa. The tower was later expanded by the Marinid dynasty and served as a coastal defense until its destruction around 1379 after Castilian conquest under Alfonso XI.

Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (18th century–present)

Carteia’s ruins attracted antiquarian interest from the early 18th century, notably identified by British Army officer John Conduitt in 1717. Subsequent travelers and scholars, including Richard Ford and the anonymous “Calpensis,” documented the site’s remains through the 19th century. Systematic archaeological excavations commenced in the mid-20th century under Julio Martínez Santa-Olalla and continued through the late 20th and early 21st centuries, led by teams from institutions such as the University of Seville.

Excavations have revealed key urban structures including the theater, forum, baths, domus, and fortifications, alongside artifacts such as coins, pottery, and inscriptions confirming the city’s Roman colonial status. The Torre de Cartagena was declared a Bien de Interés Cultural in 1949, with protective boundaries established in 2007. Despite industrial development in the vicinity, including an oil refinery that has damaged some peripheral remains, the main archaeological area remains preserved and accessible. Many finds are curated at the Carteia Archaeological Museum in San Roque.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Phoenician Foundation and Punic Period (7th–3rd century BCE)

The initial inhabitants of Carteia were Phoenician settlers who established a small trading post on the Cerro del Prado promontory, strategically positioned to monitor maritime traffic through the Pillars of Hercules. The community comprised Phoenician merchants and indigenous peoples, forming a culturally hybrid society with social stratification likely including elite traders, artisans, and laborers. Under Carthaginian Barcid influence in the 4th century BCE, the settlement expanded into a larger urban center featuring Hellenistic-inspired urban planning and fortified by a casemate wall.

Economic activities centered on maritime trade, facilitated by the port and control of surrounding land and sea routes. Satellite sites supported agricultural production and defense. Domestic dwellings were modest, with limited evidence of interior decoration. The diet likely consisted of Mediterranean staples such as cereals, olives, fish, and shellfish. Trade networks brought imported goods, including luxury items typical of Phoenician commerce. Religious practices combined Phoenician polytheism with local traditions, as indicated by temple remains and ritual architecture.

Roman Conquest and Colonial Establishment (3rd–1st century BCE)

Following Roman conquest, Carteia underwent demographic and administrative transformation. The establishment of Colonia Libertinorum Carteia introduced a population of freedmen descended from Roman soldiers and local women, creating a mixed community of Roman colonists and indigenous inhabitants. Social hierarchy included colonial magistrates, artisans, freedmen, and native residents, with inscriptions attesting to civic officials such as duumviri overseeing municipal governance. The granting of Latin Rights fostered integration and legal innovation, allowing residents to marry Roman citizens and engage in commerce.

Economic life flourished with large-scale production of amphorae, wine, and garum fish sauce, supported by workshops and kilns in the Alfarera district. Maritime trade connected Carteia to Mediterranean markets, while local agriculture sustained the population. Residential architecture featured domus with atria and mosaic floors, reflecting Roman domestic styles and social status. The forum served as a commercial and civic hub, hosting temples, shops, and administrative buildings. Religious life centered on Roman polytheism, with temples dedicated to traditional deities and civic festivals punctuating social life.

Imperial Roman Period (1st century BCE–3rd century CE)

Under the early Empire, Carteia maintained its status as a municipium within Baetica, with an ethnically diverse population of Roman citizens, freedmen, and local inhabitants. Civic life was organized around municipal councils and magistracies, as evidenced by coinage and inscriptions. Urban renewal projects under Augustus improved public amenities, including the forum, baths, and theater, which hosted cultural events and social gatherings. Residential quarters featured elaborately decorated domus with mosaic floors and painted walls, indicating wealth among the elite.

Economic activities continued to focus on amphora production, wine export, and garum manufacture, with archaeological evidence of large kilns and workshops. A hiatus in pottery production, likely caused by a tsunami in the early 1st century CE, temporarily disrupted industry. Diet remained consistent with Mediterranean staples, supplemented by seafood from the bay. Markets in the forum provided goods ranging from local produce to imported luxury items. Transportation relied on maritime routes and well-maintained roads connecting Carteia to other Baetican centers. Religious practices included traditional Roman cults, with temples maintained and public rituals observed. Over time, Christian influences began to emerge, foreshadowing later religious shifts.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th–6th centuries CE)

During Late Antiquity, Carteia experienced demographic continuity with gradual cultural transformation as Christianity supplanted pagan religions. The population included Romanized locals and Visigothic settlers, as reflected in the Visigothic necropolis where tombs reused earlier Roman architectural materials. Civic structures persisted but showed signs of adaptation, with the foundation of an early Christian basilica near the forum indicating organized ecclesiastical presence. Christian burials and funerary customs reveal evolving religious identity and social practices.

Economic activity diminished relative to earlier periods but remained sufficient to support local needs, with reduced amphora production and continued fishing and agriculture. Domestic life likely became more modest, with fewer elaborate decorations documented. Markets and trade contracted, focusing on regional exchange. Transportation networks remained functional but less intensive. Byzantine occupation in the 6th and 7th centuries integrated Carteia administratively into the province of Spania, maintaining some urban functions and defense. Religious life centered on Christianity, with bishops or church leaders assuming civic prominence.

Islamic and Medieval Period (8th–14th centuries CE)

Following the Umayyad conquest, Carteia—known as Qartayanna—contracted into a small village with a predominantly Muslim population. Although no mosque remains have been found, Arabic sources attest to its presence, suggesting religious and cultural transformation. The population likely included Muslim settlers alongside residual Christian and indigenous groups, with social organization oriented around Islamic law and local governance.

Economic life centered on subsistence agriculture, fishing, and limited trade, with the settlement’s reduced size reflecting diminished regional importance. Domestic architecture adapted to Islamic styles, though archaeological evidence is sparse. Markets would have offered local produce and imported goods via Mediterranean trade routes. Transportation relied on coastal navigation and rural pathways. Religious practices focused on Islam, with communal prayers and festivals shaping social life.

The medieval period saw renewed strategic significance with the construction of the Torre de Cartagena by the Nasrid Kingdom in the early 13th century, later expanded by the Marinids. This fortress served as a coastal defense and military outpost, reflecting the site’s role in regional conflicts. The tower’s destruction after Castilian conquest marked the decline of medieval occupation. Overall, Carteia transitioned from a Roman urban center to a modest Islamic village with intermittent military importance.

Remains

Architectural Features

Carteia’s archaeological remains encompass approximately 27 hectares on a coastal plateau near the Bay of Gibraltar. The site preserves a complex urban fabric reflecting continuous occupation from the Phoenician through medieval periods. Construction techniques include squared ashlar masonry with mortise-and-tenon joints, particularly evident in the Punic defensive walls. The city’s architecture comprises civic, religious, residential, and military structures primarily built of sandstone and local materials. The urban area expanded significantly during the Punic and Roman periods, with contraction and reuse evident in Late Antiquity and the medieval era. Present-day visible remains include fortifications, public buildings, and domestic quarters, though many areas remain partially buried or overgrown.

The city walls represent some of the best-preserved Punic fortifications in the Iberian Peninsula. They consist of a casemate design with two parallel walls approximately three meters apart, constructed with large squared blocks joined by mortise-and-tenon joints. Originally, the walls featured square towers spaced along their length, as documented in mid-20th-century plans. Roman builders reused sections of these walls during the Republican period, incorporating bastions discovered in recent excavations. The medieval Torre Cartagena, a tower-fortress north of the ancient city, exemplifies later military architecture from the 13th to 14th centuries, initially constructed by the Nasrid Kingdom and expanded by the Marinids.

Key Buildings and Structures

Theatre

The Roman theatre, dating to the 1st century BCE, is situated within the urban core of Carteia. It preserves remains of the semicircular seating area (cavea), the stage building (scaena), and approximately two-thirds of the seating tiers (gradins). Although partially buried, the theatre is identifiable on the surface and is comparable in size to the theatre of Mérida, exceeding the dimensions of other Baetican theatres such as those at Malaca and Itálica. The structure was first described in the 18th century, with earlier accounts mistakenly identifying it as an amphitheatre.

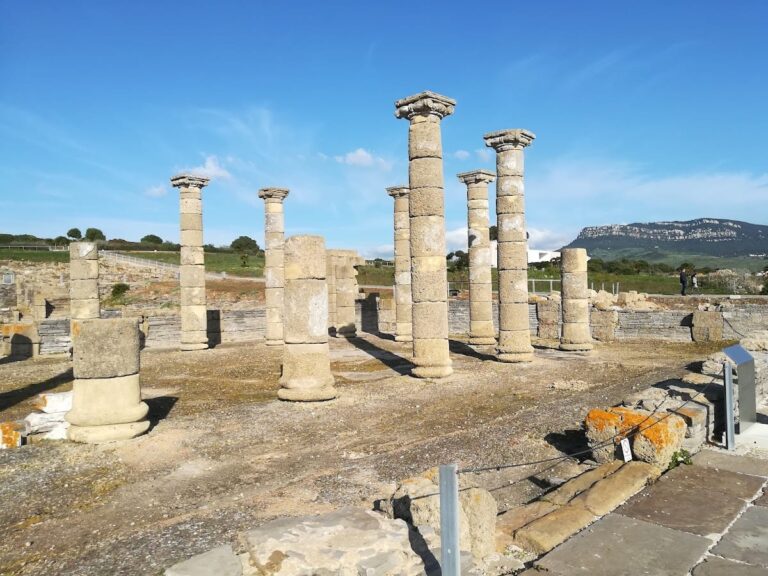

Forum and Temple

The forum occupies a natural elevation known as El Cortijo del Rocadillo and dates primarily to the late 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE, corresponding to the Augustan refoundation. Within the forum area, a Republican-era temple is attested by the remains of a square podium measuring approximately 18 meters per side. Excavations have uncovered architectural elements including fluted columns, Corinthian capitals, bull protomes (decorative bull heads), and cornices adorned with vegetal motifs. The temple shows evidence of later Christian use, with burials found around and above its remains.

At the foot of the temple podium are tabernae, enclosed commercial spaces likely functioning as shops or workshops. Adjacent to the forum is a domus with preserved remains of an atrium. This residence dates to the Augustan period but suffered partial destruction due to terrace collapse, which removed its rear section. Much of the forum remains unexcavated due to the presence of the Cortijo de Rocadillo farmhouse.

Roman Baths (Thermae)

The Roman baths date to the 1st century CE and include identifiable sections of the caldarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath), and a natatio (swimming pool). The hypocaust heating system is evidenced by preserved columns that supported suspended floors, particularly in the tepidarium. The baths are partially preserved and were in use during the Roman imperial period.

Domestic Buildings

Besides the domus near the forum, other domestic structures have been identified but are less well documented. The excavated domus exhibits construction techniques typical of the Augustan era, including an atrium layout. The rear part of this house was lost due to terrace collapse. Additional residential remains are known from surface surveys and limited excavations.

City Walls and Fortifications

The city’s defensive walls originate in the Punic period, constructed as a casemate wall with two parallel stretches approximately three meters apart. Built with squared ashlar blocks joined by mortise-and-tenon joints, these walls reflect Punic-Hellenistic architectural styles. The walls originally included square towers spaced along their length, as documented in mid-20th-century plans. Although much of the wall is now destroyed or overgrown, excavations in 2009 uncovered four bastions reused in the Republican period, along with coins minted locally between 103 and 30 BCE.

The medieval Torre Cartagena, located north of the ancient city, was built in the early 13th century by the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada as a watchtower. It was later expanded by the Marinids into a fortress with a bastion tower and gate. The tower was abandoned and destroyed around 1379 following Castilian conquest. The Torre Cartagena is protected as a Bien de Interés Cultural, with a designated protected area including the tower and surrounding land. Modern refinery pipelines near the tower have damaged some nearby archaeological remains.

Economic Structures

Archaeological evidence from the district of Alfarera, situated approximately 3 km east of the Guadarranque river mouth, reveals a Roman potters’ quarter. This area contains kilns and workshops for pottery production, including amphorae and tableware. Finds include ceramic debris, glass fragments, and slag, indicating craft activity. A production hiatus in the first half of the 1st century CE is linked to a tsunami event identified through emergency excavations in 2009.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Carteia have yielded a diverse assemblage of artifacts spanning from the late first millennium BCE through Late Antiquity. Pottery finds include locally produced amphorae used for wine export and garum fish sauce, as well as tableware and storage jars. Ceramic debris from the potters’ quarter demonstrates craft production phases interrupted by natural events.

Inscriptions recovered at the site confirm the city’s status as a Roman colonia and municipal center. These include dedicatory texts and official formulas related to local administration. Coins minted in Carteia date from approximately 103 BCE to the late Republican period, attesting to active local minting and economic activity.

Tools and domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels have been found in residential areas, reflecting daily life. Religious artifacts include architectural fragments from the Republican temple and Christian burials associated with an early basilica foundation. Visigothic tombs constructed with reused Roman materials have been documented in a necropolis near the temple area.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Carteia exhibit variable preservation. The Punic city walls, though fragmentary, represent some of the best-preserved casemate fortifications in the Iberian Peninsula. The Roman theatre retains substantial structural elements, albeit partially buried. The forum and temple area have been excavated but remain partially covered by modern farm buildings, limiting full exposure.

The Roman baths survive in partial condition, with hypocaust columns and pool structures visible. The domus near the forum is fragmentary due to terrace collapse. The medieval Torre Cartagena remains as a ruin but retains identifiable architectural features and is legally protected. Some archaeological areas have suffered damage from nearby industrial development, particularly refinery pipelines.

Ongoing archaeological projects since the 1990s have expanded excavations and conservation efforts, focusing on the Cortijo del Rocadillo area and the Torre Cartagena. The site is protected under Spanish heritage laws as a Bien de Interés Cultural, with active management to preserve visible remains.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the forum remain unexcavated due to the presence of the Cortijo de Rocadillo farmhouse, which restricts archaeological access. Surface surveys and historic plans indicate additional buried structures, including possible market buildings (macellum) and other urban features, but these have not been fully studied.

Other parts of the city, including residential quarters and peripheral districts, await systematic excavation. Modern industrial development near the site limits access to some areas. Future archaeological work is planned but constrained by conservation policies and land use considerations.