Transport and Travel in Ancient Rome

Table of Contents

Introduction

Whether for political duties, commercial ventures, military campaigns, or pilgrimages to sacred sites, the people of Rome were constantly on the move. The empire’s expansive territory, stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia, demanded an efficient and reliable transport network, one that became the backbone of Roman administration, trade, and cultural integration.

Whether for political duties, commercial ventures, military campaigns, or pilgrimages to sacred sites, the people of Rome were constantly on the move. The empire’s expansive territory, stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia, demanded an efficient and reliable transport network, one that became the backbone of Roman administration, trade, and cultural integration.

While many imagine the ancient world as static, Rome’s citizens and subjects were remarkably mobile. Politicians regularly traveled between cities and provinces; soldiers marched thousands of kilometers over the course of their careers; merchants moved goods across land and sea; and pilgrims journeyed to temples, oracles, and healing sanctuaries. Travel was an integral part of Roman life, shaped by season, status, and purpose.

Modes of Transport

Short-distance travel was often done on foot, especially by the lower classes or those with minimal baggage. Walking was inexpensive, flexible, and common across the social spectrum. Wealthier Romans, particularly in cities, used litters (lecticae)—covered couches carried by slaves. Though slow, litters offered privacy and a degree of comfort while avoiding interaction with the urban crowd.

For longer distances, Romans turned to pack animals. Horses, mules, and donkeys were preferred depending on the terrain and load. Wealthier travelers often rode horseback or used animals to carry gear, while iron sandals or “hipposandals” protected the animals’ hooves on paved roads. Government officials and couriers had access to the cursus publicus, the official postal and transportation service that utilized relays of horses and fresh vehicles at regular intervals.

Carts and Carriages

Carts were essential for transporting goods and people over longer distances. They came in various forms: From the heavy, two-wheeled plaustrum used for agricultural produce to the more elegant carpentum, a covered two-wheeled carriage reserved for women and high-ranking individuals. The angaria was a four-wheeled mail wagon used by state messengers, while other types, such as the raeda, could carry up to eight passengers and baggage.

Carts were essential for transporting goods and people over longer distances. They came in various forms: From the heavy, two-wheeled plaustrum used for agricultural produce to the more elegant carpentum, a covered two-wheeled carriage reserved for women and high-ranking individuals. The angaria was a four-wheeled mail wagon used by state messengers, while other types, such as the raeda, could carry up to eight passengers and baggage.

City laws restricted cart use during the day due to congestion. In Rome, carts were typically banned from city streets from sunrise to mid-afternoon, except for those used in religious ceremonies or state functions. This led to nocturnal deliveries and bustling streets after dark, especially near markets and warehouses.

Travel Distances and Speed

Roman travel speeds varied by season, road condition, and purpose. In summer, a traveler could walk or ride about 30 to 40 kilometers a day. Public coaches and couriers, using relay stations, might double that distance. Julius Caesar once covered 1,280 kilometers in just eight days, and there are reports of messengers traveling over 500 kilometers in a day and a half. These records underscore the logistical capacity of the empire.

Travel during winter was slower and more hazardous due to poor road conditions and shortened daylight. Heavy rains could wash out roads, while snow in the Alps made certain routes impassable. Travelers planned accordingly, avoiding difficult mountain passes and bringing gear suited to the season.

Roads and Milestones

Roman roads were the arteries of the empire, enabling the swift movement of armies, goods, and information. Constructed with stone paving, drainage ditches, and rest stops, these roads linked Rome to all corners of its domain. The saying all roads lead to Rome had a literal basis: over 400,000 kilometers of roads radiated outward from the capital.

Roman roads were the arteries of the empire, enabling the swift movement of armies, goods, and information. Constructed with stone paving, drainage ditches, and rest stops, these roads linked Rome to all corners of its domain. The saying all roads lead to Rome had a literal basis: over 400,000 kilometers of roads radiated outward from the capital.

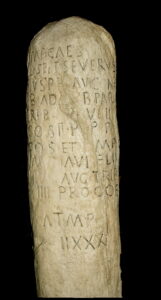

Milestones (miliaria) were placed along major routes to indicate distances. The Roman mile, or mille passus, measured approximately 1,478 meters. Milestones often included the distance to Rome, the name of the emperor responsible for repairs, and other useful information. This system helped travelers estimate their journey time and reassured them they were on the correct route.

Inns and Rest Stops

Travelers could find shelter at mansiones and mutationes (official waystations offering accommodation), stables, and fresh horses. Wealthy travelers often stayed at their own rural villas or in private homes. For most others, tabernae (roadside inns) were the standard option.

Tabernae varied in quality. A typical inn had a stable for animals, a kitchen, and modest guest rooms. Meals were served in a common dining area, often featuring stews, bread, and wine. Inns near major roads or ports might also offer entertainment, including music and, in some cases, prostitution. Despite their necessity, many inns had a poor reputation for theft, unsanitary conditions, or inflated prices.

Sea and River Travel

Maritime travel was faster than land travel and crucial for long-distance movement across the Mediterranean. Ships connected major ports like Ostia, Alexandria, Carthage, and Antioch. Coastal sailing was common, with ships hugging the shoreline to reduce the risk of storms. However, sea travel carried dangers—shipwrecks, pirates, and poor weather could all disrupt voyages.

Under favorable conditions, a journey from Rome to Alexandria might take 10 to 20 days. Returning, however, could be significantly slower due to prevailing winds. River transport was also important, especially along the Tiber, the Nile, and the Rhône, where barges moved grain, wine, building materials, and passengers.

Roman travel by sea and river

Travel Preparations

Roman travelers packed carefully. Essential items included sturdy footwear, cloaks for cold weather, writing tablets, oil lamps, and coin pouches. Wealthier individuals might carry a sundial for timekeeping and bring a retinue of slaves to manage food, bedding, and security. Women traveling alone often disguised jewelry to avoid attracting thieves.

Letters of introduction were important for gaining hospitality in unfamiliar cities. Travelers also carried documents for identification or official duties, especially if using the cursus publicus. Precautions were necessary: travel insurance didn’t exist, and a single accident or robbery could derail a journey.

The Role of Travel in Roman Society

The Roman world was remarkably connected. Roads and ships enabled emperors to rule, legions to move, and cultures to interact. Merchants, scholars, entertainers, and artisans all contributed to the cultural and economic life of the empire thanks to this mobility. Latin and Greek spread across continents, Roman law was exported to provinces, and exotic goods flowed into the capital.