Indo-Roman Maritime Trade

Table of Contents

Opening Sea Lanes to the East

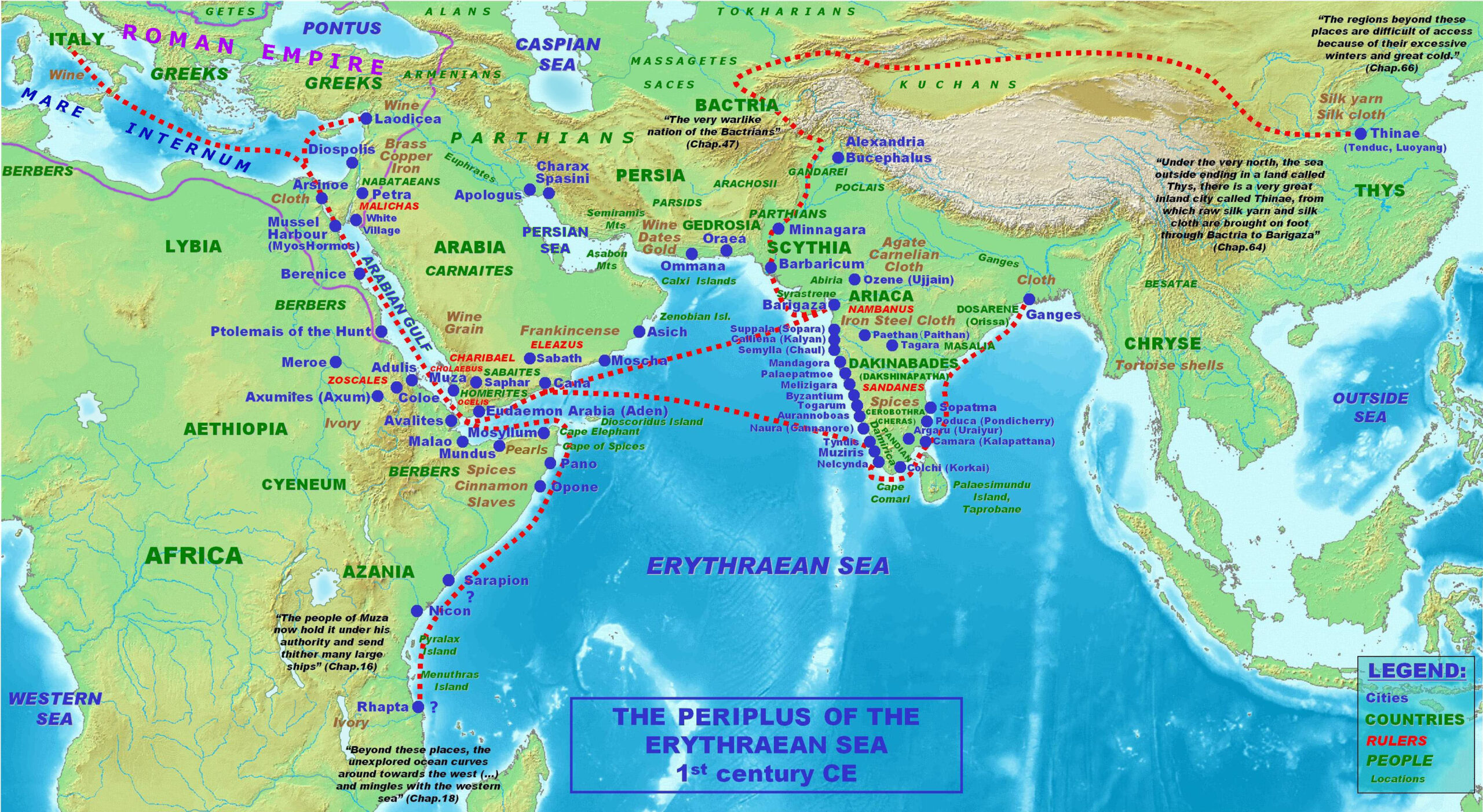

Roman ships did not confine themselves to the Mediterranean and European rivers. They ventured down the Red Sea and into the Indian Ocean, connecting the empire to the farthest lands of the East. This Indo-Roman maritime trade was one of the great commercial enterprises of the early imperial era.

From the port of Alexandria, goods and sailors would travel upriver to the Nile city of Coptos, then overland by caravan across the Eastern Desert to Egypt’s Red Sea ports: Berenike and Myos Hormos. These dusty ports bustled with Roman, Greek, and Egyptian merchants loading cargo onto seagoing ships bound for Arabia and India.

Navigating the Monsoon System

Crucial to this trade was the discovery of the monsoon wind system. Greek navigators learned (according to legend, the pilot Hippalus around 120 BCE) that the Indian Ocean’s winds change direction seasonally. By catching the southwest monsoon in summer, Roman ships could sail directly from the Red Sea to the west coast of India, and by riding the northeast monsoon in winter, they could sail back.

This eliminated the need to hug the coastline and dramatically shortened voyage times. Strabo notes that after the Roman annexation of Egypt, “as many as 120 ships” were departing Myos Hormos for India each year, compared to the few who dared the voyage under the Ptolemies. The Roman state encouraged this trade by securing routes to the Red Sea and suppressing piracy around the Arabian Sea.

Indian Ports and Roman Demand

By the mid-1st century CE, a thriving, direct sea route linked the Roman world with the western coast of India, known in ancient sources as Limyrike (modern Kerala and Tamil Nadu). Key ports included Barygaza (Bharuch), Muziris (likely in Kerala), and Arikamedu (near Pondicherry).

Muziris stood out as a commercial hub. The Periplus Maris Erythraei described it as “abounding in ships from Arabia and by the Greeks,” referring to Roman-Egyptian traders. Muziris had a temple of Augustus, suggesting semi-permanent Roman presence or official links.

Commodities Exchanged

To Indian ports, Roman ships brought wine, olive oil, glassware, and gold and silver coin. In return, they received a luxury catalog of ancient goods: pepper, cinnamon, cassia, ginger, turmeric, cardamom, frankincense, myrrh, fine cotton textiles, Chinese silk, gemstones, and pearls.

Pepper was especially critical. As Pliny noted, “there is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of fifty million sesterces” for pepper and other luxuries. India, China, and Arabia together absorbed around 100 million sesterces annually.

Roman glassware was highly prized in India. Coins featuring emperors from Augustus to Tiberius and later have been found in large hoards. The Periplus also mentions exports of copper, tin, lead, coral, and wine. Amphora fragments found in Indian digs testify to the reach of Mediterranean products.

Archaeological Footprints

Sites like Arikamedu have yielded Roman wine amphorae, glassware, coins, and pottery with Latin inscriptions. One scholar in the 1940s dubbed it a Roman trading station of the early 1st century AD.

On the west coast, Muziris’s location was lost, but discoveries at nearby Pattanam in Kerala, including Roman amphorae and a carved Roman intaglio, support its identification.

At Berenike in Egypt, archaeologists have found Indian black peppercorns, Indonesian cloves (likely via India), teak planks, and even a small Indian Buddha figurine. These finds suggest not only Roman voyages east but Indian traders reaching African and Arabian ports.

Ancient Descriptions and Practical Knowledge

The Periplus gives practical advice: when to sail, which ports to visit, and how to navigate local political conditions. It advised departure from Egypt around July to reach India by September.

Pliny the Elder lamented the costs of eastern luxuries in Book 6 of his Natural History, estimating Rome’s eastern trade deficit. He also described the seasonal rhythm of the voyage: outbound in summer, wintering on India’s coast, and returning with the December or January monsoon.

Strabo marveled at the volume of trade under Augustus, calling it unprecedented that so many Roman ships sailed to India each year.

Broader Impact of Indo-Roman Trade

This trade introduced Indian pepper and silk to Roman homes and influenced cultural perceptions. Indian embassies even reached Augustus’ court around 20 BCE. Some Indian kingdoms minted coins imitating Roman aurei, showing how Roman gold permeated eastern economies.

The trade remained strong through the 2nd century. It began to decline in the 3rd century amid Roman internal crises and renewed Persian threats. However, Byzantine traders continued Indian Ocean commerce into the 7th century until the rise of Arabian maritime dominance.

Indo-Roman maritime exchange stands as one of history’s earliest examples of global trade. It connected the Mediterranean world with India through daring voyages and complex networks of exchange.