Phoenician Religion and Ritual Practices

Table of Contents

Phoenician religion evolved in a network of independent cities, lacking a single centralized authority yet sharing a coherent cultural framework. Each city-state revered its own patron deities and local traditions, but common themes and gods tied the region’s spiritual life together. Reconstructing Phoenician beliefs is challenging because no native mythological texts or scriptures survive. Scholars rely on clues from inscriptions, temple ruins, and accounts by later Greek and Roman writers. Despite sparse texts, archaeology shows that religion permeated both daily life in Phoenician port cities and the far-flung colonies they founded across the Mediterranean.

The Pantheon Across the Phoenician World

The Phoenician pantheon featured many gods and goddesses, often with overlapping roles. While each city had favored patrons, several major deities were worshipped across Phoenicia and its colonies:

- Melqart (Tyre): Patron god of Tyre, associated with kingship, the sea, and commerce. The Greeks likened him to Hercules, reflecting his role as a powerful protector and founder of colonies.

- Astarte (Sidon and beyond): A great goddess of fertility, love, and war. Also known as Ashtart, she was venerated in multiple cities. Sidon’s kings styled themselves as priests of Astarte, highlighting her importance in state religion.

- Baal: A title meaning “Lord,” used for various local storm and sky gods. One prominent form was Baal Shamem (Lord of the Heavens), a weather deity invoked for rain and prosperity. Many Phoenician gods carried the name Baal with epithets (Baal of Sidon, Baal Hammon, etc.).

- Eshmun (Sidon): God of healing and renewal. Sidon’s chief male deity, Eshmun was connected with health and was later identified with the Greek Asclepius due to his healing functions.

- Baal Hammon (Carthage): The principal god of Carthage in later times, thought to ensure agricultural fertility and the prosperity of the community. He was often depicted as a robed older figure and was equated by the Greeks to Cronus or by Romans to Saturn.

- Tanit (Carthage): The great goddess of Carthage, introduced in the West and possibly influenced by local Libyan deities. Tanit was a motherly figure of life, fertility, and protection. She was called “face of Baal” and became the consort of Baal Hammon, eventually rising to supreme prominence in Punic worship.

Many of these deities were known by different names or aspects in various regions, yet their core identities transcended any single city. For example, Phoenicians in Cyprus worshipped a love goddess similar to Astarte, and Spanish Phoenician colonies honored Melqart in temples far from Tyre. As Phoenician traders and settlers spread westward, they carried their gods with them. In new lands, the old pantheon sometimes absorbed traits of indigenous gods or vice versa. This colonial adaptation is evident in Carthage, where the Tyrian gods were venerated alongside new figures like Tanit. Despite local variations, a worshipper from Sidon would recognize the major gods honored in Carthage or Sardinia, reflecting a shared Phoenician-Punic religious heritage.

Temples

Temple Architecture and Sacred Symbols

Phoenician temples stood as prominent landmarks in cities and sanctuaries. These sacred buildings were often positioned in important locations, such as a city’s acropolis (fortified high area) or near the bustling harbor, symbolizing the deity’s importance in civic life. The architectural design followed Near Eastern traditions, typically built on a raised podium (platform) with a few steps leading up to the main structure. A standard temple plan consisted of a porch and one or more chambers, with the cella (inner sanctum) serving as the sacred heart of the building where the deity’s essence was believed to reside. Interestingly, Phoenician cults did not always feature large idol statues in the cella. Instead, sacred objects or symbols, such as a carved pillar or an eternal flame, could represent the divine presence. One notable example is the ancient Temple of Melqart at Tyre, where historical accounts describe two grand pillars at its entrance and a holy fire but no conventional statue of the god. Twin columns flanking the doorway were a characteristic element, famously echoed in the Biblical description of Solomon’s Temple, which incorporated Phoenician craftsmanship.

Ritual Practices and Civic Functions

Ritual activities in Phoenician temples often unfolded in open courtyards adjoining the temple halls. An altar stood prominently in front of the temple, exposed to the sky, providing a space where worshippers gathered for sacrifices, burnt offerings, and prayers. The temple’s inner rooms stored cult paraphernalia and treasures, reflecting the temple’s dual role in religious and practical community life. Beyond worship, temples also served as treasuries and archives, safeguarding wealth and important documents under divine protection. In several Phoenician cities, temples functioned as places for recording contracts or treaties, underscoring their status as trusted civic institutions. Archaeological discoveries offer glimpses into these sacred spaces. At Sidon, the Temple of Eshmun, dedicated to the healing god, was built near a river and featured basins for ritual purification by water. Its ruins reveal a large stone podium and a monumental stairway, suggesting a processional approach to the sanctuary. At the small port of Sarepta, excavations uncovered a modest shrine with an altar, offering pits, and cult vessels, illustrating how even smaller communities maintained local temples.

Sacred Architecture Across the Phoenician World

Carthage, despite later Roman destruction, is known from inscriptions to have housed numerous temples dedicated to various gods. These Punic temples likely resembled their Phoenician predecessors, combining enclosed sanctuaries with open-air altars. Whether along the Lebanese coast or in distant colonies like Spain, Phoenician sacred architecture maintained a consistent balance between enclosed holy spaces and open-air ritual courts. This combination provided settings not only for personal devotion but also for public worship and civic ceremonies. The enduring features of Phoenician temple design reflect a cultural emphasis on both the mystery of the divine housed within sacred chambers and the communal aspect of worship performed under the open sky.

Rituals and Festivals

Phoenician worship involved a rich array of rituals to honor the gods and secure their favor. Daily offerings and special sacrifices formed the backbone of religious practice. Key types of offerings included:

- Incense and libations: Fragrant resins were burned on altars, and libations (ritually poured liquids like wine, oil, or water) were offered to please the gods’ senses. Sweet smoke and poured drinks were seen as nourishment for divine beings and a way to carry prayers upward.

- Animal sacrifice: Domestic animals such as sheep, goats, cattle, or birds were slaughtered and burned in dedication to the gods. The choice of animal often depended on the deity and occasion. Portions of the meat could be shared in a sacred meal by priests or worshippers after the deity received its due, binding the community and the god through the feast.

- Food and drink offerings: In addition to or instead of animals, people presented agricultural produce – bread, grain, olives, fruits, honey, and wine. These gifts thanked the gods for bounty and sought continued blessings for crops and households.

- Precious goods: On important occasions, worshippers donated valuable items such as finely crafted pottery, metal vessels, jewelry, or purple-dyed cloth. Such dedications, often inscribed with the donor’s name, were left in temples as lasting tributes.

Worshippers also dedicated numerous votive objects to accompany their prayers. Small clay figurines depicting deities or worshippers in prayer were common temple offerings, left as tokens of devotion or in hopes of divine help. Carved stone stelae (upright slabs) inscribed with prayers or thanks were erected in sanctuaries to commemorate fulfilled vows. Amulets and plaques bearing sacred symbols or images of gods were deposited as well, especially in healing or fertility cults, to solicit protection. These material offerings created a tangible connection between people and their gods, filling Phoenician sanctuaries with a clutter of devotion over the centuries.

Festivals and communal rituals likely marked the Phoenician religious calendar, although specific festival names and dates are not recorded. By analogy with related Semitic cultures, we can infer seasonal celebrations for harvests or the new year where the whole city participated. During these events, temples would host processions: priests carrying cult emblems or sacred objects through the streets, accompanied by musicians playing lyres, drums, and trumpets. Iconographic evidence – such as bronze bowls engraved with lines of dancers or figurines of drum-playing women – hints that music and dance were part of Phoenician sacred ceremonies. Participants might sing hymns or perform ritual dances in honor of gods like Baal or Astarte, invoking mythic stories through movement. Religious ceremonies could be solemn or ecstatic: in the cult of Astarte, for instance, there are accounts (from later classical sources) of frenzied dances or even ritual prostitution as extreme acts of devotion. While details are scarce, it is clear that Phoenician religion was not a quiet affair; it engaged all the senses. The lighting of incense, ringing of sistrums (musical rattles), and chanting of prayers during festivals would unite the community in shared sacred experience. These public rituals reinforced social bonds and affirmed the gods’ central place in Phoenician urban life.

The Tophet Debate: Sacrifice or Cemetery?

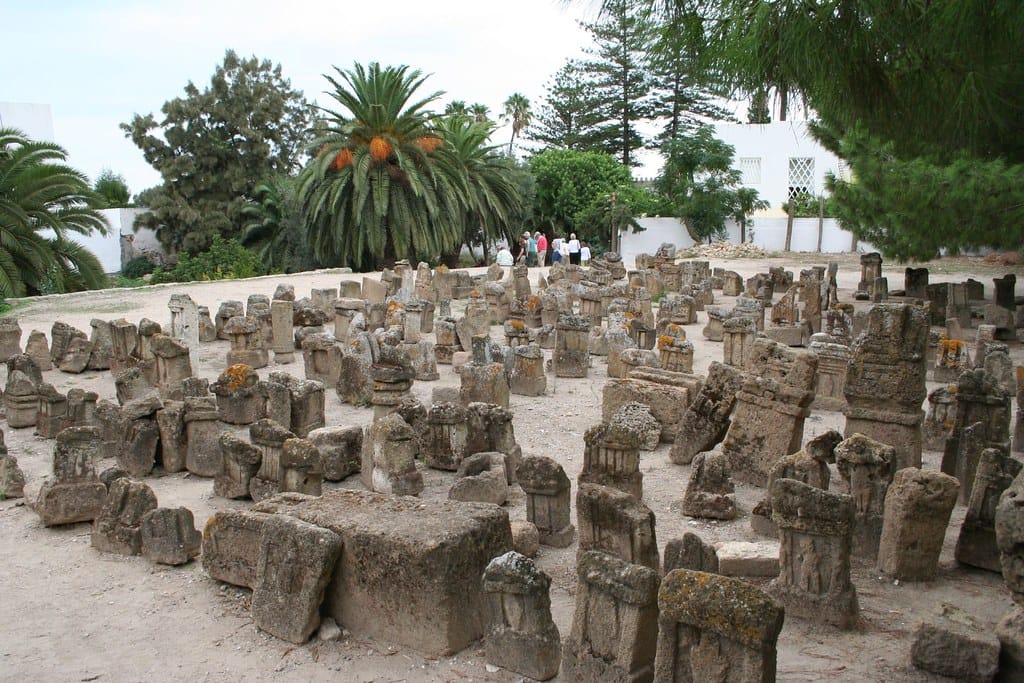

Above: View of the Tophet of Carthage, a sacred precinct filled with burial urns and stone stelae. This open-air enclosure was used between roughly the 8th and 2nd centuries BCE. Thousands of urns containing cremated remains of children and animals were interred here under inscribed markers, reflecting a unique and controversial aspect of Phoenician-Punic ritual.

Among the most debated features of Phoenician and especially Carthaginian religion is the Tophet – a term used for certain sacred enclosures containing urns of cremated bones. These tophets were typically located just outside city limits. They consist of open ground crowded with small burial urns, each often topped by a stone slab or stela dedicated to a deity. Major tophet sites have been found in the western Phoenician colonies: the largest example in Carthage (the “Precinct of Tanit”), others in North Africa such as at Hadrumetum (modern Sousse, Tunisia) and in the Phoenician settlements of Sardinia (like Sulcis and Tharros). In the Levantine homeland, evidence is scant: No clear tophet has been excavated in Tyre or Sidon, though classical sources imply the practice may have existed there in some form. The contents of the urns are striking: a high proportion of the remains are those of infants and very young children, sometimes mixed with bones of sacrificial animals (typically lambs or kids). This discovery gave rise to the traditional interpretation that tophets were ritual sites for child sacrifice, where Phoenicians offered their offspring to the gods in exchange for divine favor.

Ancient Testimonies and Traditional Interpretations

Classical authors and the Old Testament present a dramatic image of this practice. Greek and Roman writers recounted how, in times of grave danger or calamity, Carthaginians would sacrifice children to appease Baal Hammon or Cronus (whom they equated with the Phoenician god). One lurid description spoke of a bronze statue of the god with outstretched arms, upon which a child was laid before sliding into a pit of fire. These accounts, combined with inscriptions on some Carthaginian stelae explicitly thanking the gods for hearing a “voice,” presumed to be the cry of a sacrifice, long led scholars to accept that the tophet burials were the result of ritual killing of children.

In this view, the tophet was effectively a sacrificial cemetery, and the practice of molk (a term appearing in inscriptions) meant a blood offering of one’s own child. The act was seen as a supreme sacrifice in exceptional circumstances, perhaps carried out by elite families or city leaders to avert disaster. If true, it suggests Phoenician values placed communal survival and piety above even parental instinct, offering what was most precious when the gods’ favor seemed lost.

Revisionist Views and Modern Interpretations

In recent decades, however, researchers have re-examined the tophet evidence and proposed a gentler interpretation. Detailed osteological studies of the remains in Carthage’s tophet reveal that the vast majority of children buried there died very young, many likely stillborn or perishing in infancy from natural causes common in antiquity. Furthermore, curiously few infant graves appear in the normal city cemeteries. This has led some scholars to argue that the tophet was not a place of killing, but rather a special burial ground for infants and children who died of illness or other causes.

In this revisionist view, grieving families would cremate their deceased infants and place the ashes in urns, dedicating them to Tanit or Baal as a way to consecrate the short-lived child to the gods. The practice could have been a form of collective mourning ritual rather than an act of sacrifice.

A Complex Legacy of Faith and Loss

Proponents of this theory note that some stela inscriptions mention the substitution of an animal for a child, and that ancient reports of child sacrifice emphasize it as a rare response to crisis, not a routine expectation. It is possible that both things are true to a degree: Phoenician cities might have ordinarily used the tophet as a sanctified children’s cemetery, yet in extreme moments of war or disaster a few actual sacrifices occurred, later magnified by enemy commentators. The tophet debate continues, but it highlights the need for nuanced interpretation of archaeological and textual evidence.

Whether sacrifice site or cemetery (or both), the tophet reflects the intensity of Phoenician religious devotion and the stresses their communities faced. It remains a poignant, if macabre, testament to how deeply religion was woven into life and death for the Phoenicians and their Punic successors.

Priestly Roles and Religious Administration

Phoenician temples were tended by a class of priests and priestesses who played vital roles in ritual and society. The term for priest in Phoenician was kohen (cognate to the Hebrew “kohen”), and inscriptions indicate that high priests bore titles such as rab-kohen (literally “chief priest,” the head of a temple’s clergy). These religious offices often ran in families and were frequently a hereditary privilege of the local elite. Royal households in particular intertwined with the priestly hierarchy: kings and princes themselves performed key rituals and sometimes officially served as high priests of the chief deity. In Tyre, for example, the king was traditionally the high priest of Melqart, and one Tyrian king even held the epithet “Priest of Astarte” as a secondary title. In Byblos, an inscription tells us that King Yehimilk built a temple, and another king, Ozbaal, was the son of a high priest of the city’s goddess. These cases show that political and spiritual authority reinforced each other in Phoenician governance. By leading worship, the ruling class legitimized their power as divinely sanctioned, and in turn the temples benefited from royal patronage.

Economic and Legal Functions of Temples

The duties of priests went beyond conducting sacrifices and prayers. They were the administrators of sacred property and guardians of religious law. Temples owned land, orchards, and workshops, which needed oversight, and priests managed these assets to ensure the gods’ estates were productive. Priestly officials kept written records of donations and fulfilled vows, essentially acting as scribes and archivists for the sanctuary. Important civic documents, such as commercial contracts, treaties, or marriage agreements (including dowries), might be stored or even finalized “before the god,” implying a temple setting with priests as witnesses. This gave legal transactions a religious validation and kept them safe under divine watch. In economic life, temples could function like banks: collecting offerings of wealth in treasuries, financing community needs, and redistributing resources during festivals or emergencies. The priesthood thus held considerable social influence, operating at the intersection of religion, law, and finance.

Ritual Hierarchies and Sacred Duties

Within the temples, a hierarchy of clergy performed specific roles. High priests supervised ceremonies and maintained the cult statue or symbol, if there was one. Lower-ranking priests (kohenim) and acolytes carried out daily tasks such as lighting the sacred fires, preparing sacrificial animals, and leading chants. Some cults also had dedicated functionaries; for instance, there were likely special priests for conducting the molk rites (if human or animal sacrifices needed particular rituals) and others who interpreted omens or oracles. There is evidence that women served as priestesses or temple personnel in certain cults, such as the priestesses of Astarte or Tanit, though the highest positions were often male-dominated. Both male and female clergy were expected to maintain purity and perform elaborate cleansing rituals. Contemporary accounts describe priests in Carthage shaving their heads and wearing plain garments, marking a life of ritual purity and separation from ordinary society. They even rubbed their bodies with red ochre during ceremonies, possibly as a sign of a sacred, otherworldly status.

Priests in Life and Death

Phoenician priests also oversaw rites of passage and funerary practices. They likely officiated at burials and memorial services, ensuring the proper rituals were done so the soul of the deceased would be at peace. The presence of spices, oils, and amulets in tombs suggests priests performed embalming or anointing of bodies, connecting to their role as healers and mediators with the afterlife. In sum, the priestly class in Phoenician culture was multi-faceted: part religious officiant, part estate manager, and part public notary. Through their hands passed both the offerings of the faithful and the records of the city, making them indispensable to the fabric of Phoenician urban life.

Religion in Colonial Contexts

Wherever the Phoenicians sailed and settled, they carried their gods and sacred practices with them. In the colonies of the western Mediterranean, Phoenician (or Punic) religion provided a spiritual bridge back to the homeland while also adapting to new surroundings.

The most famous colony, Carthage in North Africa, offers a prime example of religious continuity and change. Founded by settlers from Tyre, Carthage initially worshipped the familiar Tyrian gods: Melqart, Astarte, and Baal among others, and even sent annual tribute back to Melqart’s temple in Tyre for a time.

As generations passed, Carthaginian religion evolved its own character. By the 5th century BCE, the goddess Tanit rose to prominence in Carthage, eventually becoming the city’s principal deity alongside Baal Hammon. Tanit may have originated from a local Berber mother-goddess fused with attributes of Phoenician Astarte; her emergence shows how colonial religion could incorporate indigenous influences. Likewise, Baal Hammon in Carthage took on a distinctive importance as “lord of the incense altars,” a role possibly inspired by earlier Libyan chief gods of the land.

Syncretism and Religious Adaptation

Phoenician settlers also encountered the gods of other cultures and often embraced or identified them with their own. In the Iberian Peninsula, for example, Phoenician-Punic communities might equate Melqart with the local Hercules-Melkart figure, blending mythologies so that even Greek and native Spanish worshippers could partake in his cult.

In Malta, Sicily, and Sardinia, excavations show that Phoenicians shared sacred space with Egyptian or Greek deities. Statuettes of Isis or Demeter appear alongside Tanit symbols, indicating a multicultural religious life in these trading hubs.

Over time, the colonial pantheon expanded: Carthage officially adopted the Greek goddesses Demeter and Kore (Persephone) after a military disaster, integrating them as protectors of the state. This syncretism is a hallmark of Phoenician religion abroad. It was flexible and inclusive, able to absorb foreign divinities while maintaining core traditions.

Sacred Spaces in the Colonies

The physical layout of Phoenician colonies also reflected their religious priorities. Urban planning typically reserved areas for temples and sacred precincts.

In new cities, settlers would establish a central temple to the patron god of the mother city. For instance, the Phoenicians in Spain built a renowned Temple of Melqart at Gadir/Cádiz, which became a pilgrimage site for centuries. Cemeteries were placed outside city walls, and, as in Carthage, a separate tophet area might be designated for special burials and sacrifices.

These sacred zones abroad often replicate the features of those in the Levant: walled sanctuaries, open-air altars, and rows of stelae. Carved motifs on colonial stelae – the sign of Tanit, the solar disc and crescent, or the spread-hand gesture of blessing – are virtually identical across sites from North Africa to Sardinia, underscoring a shared religious iconography throughout the Punic world.

Religion as Cultural Continuity

Such continuity in symbols and practice gave Phoenician colonists a sense of common identity and divine protection, even when they were far from their ancestral cities.

In essence, religion was a portable homeland for the Phoenicians: no matter where they founded a new port or trading post, the gods were invited to settle there too, anchoring the community in familiar sacred traditions while accommodating the gods of their neighbors.

Symbols, Inscriptions, and Material Religion

Above: A Punic stele from North Africa bearing a carved Tanit symbol (triangle with circle and horizontal bar) under a crescent moon. Such symbols were common on Phoenician and Carthaginian religious monuments, serving as a shorthand for the presence of the goddess and the heavens watching over the dedication.

Symbols and Sacred Imagery

Phoenician religion expressed itself not only in temples and ceremonies but also through a rich visual and written culture of symbols. Certain icons appear again and again in Phoenician and Punic sacred art, conveying theological concepts in simple form.

One of the most ubiquitous is the Tanit symbol: a basic schematic figure composed of a triangle (sometimes shaped like a skirt or altar base) topped by a straight line and a disk. This emblem is often interpreted as a stylized female form or a sign of life and fertility associated with the goddess Tanit. It adorns hundreds of Carthaginian stelae, amulets, and even coins.

Alongside it, the sun-disc and crescent moon motif frequently appears, either above the Tanit sign or on its own. The disc-and-crescent symbolizes cosmic powers, the sun and moon, and by extension the favor of celestial gods (like Baal Shamem, lord of the sky). Another common image is the palm tree, shown as a date palm with spreading fronds; the palm represented prosperity and was sacred especially to Tanit as a life-giving Mother Earth figure.

Doves, too, are depicted on some votive stelae and jewelry, as birds associated with love and the feminine divine (Astarte was often linked with doves). These symbols allowed worshippers, many of whom may not have been literate, to recognize which deity was honored and the general prayer being offered.

The Phoenicians tended toward aniconic representation, meaning they often used symbols or abstract forms to stand in for gods rather than detailed human-shaped idols. A simple engraving of a crescent over a circle on a stone could thus mark that stone as a sacred marker invoking the heavens’ blessing on an offering.

Inscriptions and Personal Devotion

Inscriptions complement these visuals, giving us direct (if brief) voices of Phoenician worshippers. Over ten thousand Phoenician and Punic inscriptions have been found, most of them religious dedications or epitaphs. They are typically concise and formulaic. A standard dedication on a stela might read, in translation: “To our Lady Tanit Face-of-Baal and to the Lord Baal Hammon, this offering was made by [Name], son of [Name], because he heard his voice and blessed him.”

This formula reveals several aspects of Phoenician piety: they explicitly name the gods (often with honorific epithets like “face-of-Baal” for Tanit, emphasizing her status as Baal’s consort or mediator), they identify the donor (signifying personal piety and perhaps status), and they state that the god “heard his voice,” implying that the prayer or vow was answered.

In funerary inscriptions, we find pleas to the gods to protect the tomb and curses upon any who disturb the dead, reflecting a belief in divine enforcement of justice. The language used in all these texts is Phoenician (or its later form, Punic), written in the Phoenician alphabet.

Even as the Phoenician people came under foreign dominion (Persian, then Hellenistic, then Roman), they continued to use their language for sacred purposes. In some cases, bilingual inscriptions (Punic and Greek or Punic and Latin) have been discovered, which have been crucial for scholars to decipher and understand Phoenician terminology for gods and rituals. These texts show continuity amid change: a late 2nd-century BCE Punic inscription in North Africa might be carved in neo-Punic script but still invoke Tanit and Baal in the old formulas, long after Carthage’s political fall.

Material Culture and Daily Worship

Apart from stone inscriptions, the material culture of Phoenician religion is rich with portable objects of faith. Clay figurines of deities, often only a few inches high, have been unearthed in temples and household shrines. Many depict a female figure (possibly Astarte or a generic “mother goddess”) holding her breasts or a child, an iconography of fertility and nurturing that ordinary families likely kept for personal devotion.

There are also bronze or pottery masks with exaggerated smiles or grimaces, sometimes found in graves or temple contexts, thought to ward off evil spirits or embody a protective presence. Personal adornments carried religious meaning too. Amulets were extremely popular; Phoenicians, being great seafarers, carried amulets featuring Egyptian gods like Bes (a dwarf-god who protected households) or the Eye of Horus (symbol of divine protection and health). They also crafted amulets with Phoenician symbols, such as mini Tanit signs or miniature sacred pillars.

Such items blur the line between daily life and worship. A trader might wear a pendant of Melqart’s symbol while sailing, or a mother might tuck a small goddess figurine into her home’s niche and pray for her children’s wellbeing. In Phoenician religion, the divine was never far from reach: it was etched in the doorways, minted on coins, painted on pottery, and worn around the neck. This material religion provided constant reminders of the gods’ presence and made worship a tactile, visible part of everyday experience.

Decline, Legacy, and Interpretive Challenges

Phoenician religion did not disappear overnight; it gradually transformed under the influence of new empires and faiths. During the Hellenistic period (after Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BCE), Phoenician cities like Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos became increasingly Hellenized. Traditional gods were identified with Greek counterparts: Melqart was equated with Heracles, Astarte with Aphrodite or Artemis, and Eshmun with Asclepius.

The worship styles also began to change, as Greek artistic styles and possibly Greek language crept into sacred spaces. Nonetheless, the core Semitic religious identity persisted, often just beneath a Greek veneer.

In the Western colonies, after Rome defeated Carthage in 146 BCE, Punic religion proved resilient. In North Africa under Roman rule, the old Punic gods were openly worshipped but under Latin names: Saturn for Baal Hammon, and Juno Caelestis (“Heavenly Juno”) for Tanit. The Romans, rather than abolishing these cults, often built new temples for them.

For instance, in the city of Dougga (Tunisia), an inscription in the 2nd century CE records a priest of Saturn who is clearly continuing the Baal Hammon priesthood. The blend of cultures is evident, carvings show Tanit’s symbol alongside Roman eagles, encapsulating a fusion of identities.

Over time, especially by the 4th century CE, Christianity spread through Phoenicia and former Punic regions, leading to the suppression of the old temples and rituals. Many Phoenician sacred sites were rededicated to new purposes or fell to ruin.

Yet, aspects of Phoenician religion left a legacy: certain festival practices, protective amulets, and religious words influenced folk traditions in the Levant and Maghreb for centuries. Even today, the names of Phoenician deities survive in literature and legend (for example, Europe learned of figures like Dido and Melqart through Greek and Roman retellings). The slow decline of Phoenician paganism thus gave way to new religious landscapes, but it did not erase the cultural memories of those ancient rites.

Fragmentary Sources and Modern Interpretations

Understanding Phoenician religion today comes with many challenges, due to the fragmentary nature of the evidence and the biases of sources. Unlike, say, Greek or Egyptian religion, we lack any comprehensive Phoenician theological texts or narrative myths preserved on clay or papyrus. Scholars have therefore had to piece together a mosaic of information from secondary sources and archaeology.

Early antiquarians in the 19th and early 20th centuries often relied heavily on the lurid descriptions in Greek, Roman, and Biblical accounts to characterize Phoenician religion. This led to a sensationalized image of the Phoenicians as sinister child-sacrificers and licentious idolaters, in line with how hostile ancient writers portrayed them.

As more archaeological data became available, those early portrayals proved to be oversimplified or sometimes outright false. Modern researchers approach Phoenician cult practices with a more critical eye, cross-comparing the evidence. For example, the story of rampant child sacrifice has been tempered by scientific analyses of tophet burials, which suggest a more complex reality (as discussed above).

Additionally, scholars use comparative methods, looking at Ugaritic texts (from a related Canaanite culture of the second millennium BCE) and Biblical traditions of the Canaanites/Israelites, to infer what Phoenician myths and rituals might have been like. These comparisons can be illuminating. For instance, Ugarit’s myth of a dying-and-rising god (Baal and Anat) might mirror lost Phoenician tales of Melqart or Adonis, but they are also risky. We must be careful not to project too much from one culture onto another. Each Phoenician city had its own historical trajectory, and their religion evolved over a millennium of geopolitical changes.

Pragmatism and Local Variations

Another interpretive hurdle is that Phoenician religion was highly pragmatic and local. It did not produce grand philosophical treatises or theological debates that we know of. Instead, what we see is a focus on ritual correctness, honoring contracts with the divine, and integrating religion with civic life.

This means our sources are things like altar inscriptions, temple foundation dedications, and votive offerings – concrete expressions of piety, but not explanations of it. As a result, historians have to infer the beliefs behind the practices. Were the Phoenicians devout out of fear, love, or tradition? How did they conceive the afterlife beyond hints of an underworld in tomb texts? Many such questions remain only partly answered.

The legacy of Phoenician religion, however, is indisputable in the archaeological record they left and the influence on successor cultures. From the spreading of the Phoenician alphabet (which first wrote those sacred words) to the transmission of iconography (the Tanit symbol, for example, appears to have inspired later mystical symbols in the region), the spiritual life of this ancient seafaring people quietly underpinned aspects of Mediterranean civilization.