Roman Funerary Practices: A Detailed Overview

Table of Contents

Rituals and customs surrounding death in ancient Rome.

Roman funerary practices encompassed the religious rituals related to funerals, cremations, and burials. These practices were rooted in the mos maiorum, an unwritten code that shaped Roman social norms. Elite funerals often included processions and public eulogies, allowing families to celebrate the deceased’s life and their own social standing. Political elites sometimes hosted public feasts and games after funerals to honor the dead and enhance their public image. Gladiatorial games originated as funeral gifts for high-status individuals.

In early Roman history, both inhumation and cremation were common across social classes. By the mid-Republic, cremation became the predominant practice, with inhumation largely replaced until the middle of the Empire. The shift back to inhumation occurred during the early Christian era. Ash-tombs, known as columbaria, were provided for the poor, while catacombs served as burial sites in later periods.

In Greco-Roman culture, the dead were seen as polluting, yet honoring ancestors was a key cultural value. The care of the dead balanced these conflicting views. Proper funeral rites were believed to transform the deceased into benevolent ancestors. Those who died prematurely or without rites were thought to haunt the living. Cicero noted that a cremation site lacked sacred status until earth was cast upon the bones, marking it as a religious place.

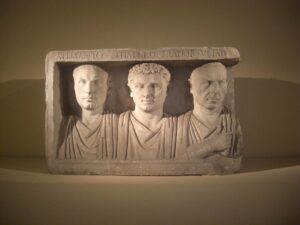

Cemeteries were traditionally located outside the pomerium, the ritual boundary of cities. Tombs, ranging from grand monuments to simple graves, lined roadsides. Living relatives regularly visited tombs, offering food and wine to the deceased. Proper observance of funerary rites was believed to ensure the favor of the deceased’s spirit towards their living descendants. Families often invested heavily in tombs and memorials, with sarcophagi featuring elaborate artwork and inscriptions.

Cemeteries were traditionally located outside the pomerium, the ritual boundary of cities. Tombs, ranging from grand monuments to simple graves, lined roadsides. Living relatives regularly visited tombs, offering food and wine to the deceased. Proper observance of funerary rites was believed to ensure the favor of the deceased’s spirit towards their living descendants. Families often invested heavily in tombs and memorials, with sarcophagi featuring elaborate artwork and inscriptions.

Regulation and Social Aspects of Funerals

Funeral displays and expenses were regulated by sumptuary laws aimed at reducing class envy. Less affluent individuals could join guilds or collegia that provided funeral services. The dead posed a risk of ritual pollution until proper funerary rites were performed, which separated them from the living and guided their spirits to the underworld. Professional undertakers organized funerals, managed rites, and disposed of bodies. Even simple funerals could be costly relative to income, while the poorest might be disposed of without ceremony.

Cicero described funeral rites as a natural duty, with the state sometimes covering costs for those who served the public. Sumptuary laws aimed to limit extravagant displays of mourning were often ignored. Some individuals attempted to evade funeral costs, leading to illegal disposal of bodies. The government contracted undertakers to manage the removal of abandoned corpses, with estimates of 1,500 such cases annually.

Population, Mortality, and Legal Practices

Rome’s high population necessitated efficient disposal of the dead. The death rate in Rome was significant, with estimates of 30,000 deaths annually among a population of about 750,000. Life expectancy varied, with many citizens living into their late fifties. Maternal mortality rates were high, and infant mortality was severe, with many children not surviving past early childhood. The law allowed fathers to abandon newborns deemed unfit, a practice that continued despite eventual prohibitions.

Family Roles and Funeral Financing

The paterfamilias, or head of the family, typically arranged and financed funerals. If the deceased was the paterfamilias, the financial responsibility fell to the heirs. Married women’s funerals were funded by their husbands or dowries. Slaves who died loyal to their families might receive decent funerals, while newborns who died before being named had fewer obligations for rites. Their deaths did not pollute, and they could be buried almost anywhere.

Professional Undertakers and Their Roles

Undertakers, known as dissignatores or libitinarii, provided various services related to funerals. Their work included digging graves, preparing bodies, and organizing processions. In some towns, undertakers also served as executioners. Regulations dictated the timely removal of bodies, especially for suicides, which were considered offensive to the gods. The Esquiline Hill likely served as the headquarters for official undertakers, with a temple dedicated to Venus Libitina, the goddess of funerals.

Burial Societies and Public Support

Burial societies were among the few private organizations accepted by Roman authorities. These societies provided funeral rites and burial for members, often funded by subscriptions. The emperor Nerva introduced a burial grant for the lower classes, which helped cover basic funeral costs. In Puteoli, a basic funeral could cost around 100 sesterces, while a respectable funeral in later periods could exceed 1,000 sesterces.

Funeral Announcements and Mourning Rituals

Funeral announcements were made publicly, especially for prominent individuals. The deceased’s body could remain at home for several days, with mourning rituals observed. Family members would gather to lament, and the body was prepared by female relatives. Mourners wore appropriate attire, with elite males donning dark togas. The body was displayed in a lifelike posture, often adorned with cosmetics to mask death’s pallor.

Timing and Public Display of Funerals

Funerals were typically held at night for the poor, while elite funerals could occur during the day. The timing of funerals varied, with some lasting several days. Public funerals provided opportunities for families to showcase their status. Eulogies were delivered to honor the deceased, often highlighting their achievements and lineage. The eulogy served as a means of public recognition for the deceased and their family.

Disposal and Sacrificial Rites

Disposal of the dead typically occurred outside city boundaries to avoid pollution. Sacrifices were made at burial sites to ensure the deceased’s passage to the afterlife. The heir would offer a pig, and the sacrifice’s acceptance was crucial for securing a resting place for the deceased. Cremation involved lighting a pyre, with ashes collected and interred afterward. Inhumation became more common over time, with cremation reserved for specific contexts.

The Novendialis and End of Mourning

After nine days, a second set of rites called the novendialis was held, marking the end of mourning. This included another sacrifice to the deceased’s spirit. The deceased was considered a deity of the underworld, and purification rites concluded the mourning period. Families would then return to normal life, often hosting a feast to celebrate the deceased’s memory.

Grave Goods and Commemoration

Grave goods varied by age and status, with adults receiving items like clothing and food, while infants might be buried with toys or protective symbols. The presence of grave goods indicated care for the deceased’s journey in the afterlife. Commemorations continued beyond the funeral, with families expected to honor their dead through regular rites and offerings.

Funeral Games and Festivals

Funeral games, or ludi funebres, were held to honor the deceased, often involving gladiatorial contests. These games became popular but were also criticized for their extravagance. Festivals like the Parentalia honored ancestors, with families visiting graves and offering feasts. Epitaphs served as lasting memorials, providing information about the deceased and their achievements. The shift to Christian epitaphs emphasized the day of death and the hope for eternal life.

Roman Funerary Art and Urban Cemeteries

Roman funerary art included imagines, or images of the deceased, displayed during funerals. These images were often made of wax and served to commemorate the deceased’s life. The tradition of creating realistic portraits contributed to the development of Roman portraiture. Urban cemeteries were often contested spaces, with laws governing burial practices to maintain the sanctity of the dead.

Roman funerary art included imagines, or images of the deceased, displayed during funerals. These images were often made of wax and served to commemorate the deceased’s life. The tradition of creating realistic portraits contributed to the development of Roman portraiture. Urban cemeteries were often contested spaces, with laws governing burial practices to maintain the sanctity of the dead.