Horst Palace: A Renaissance Castle in Gelsenkirchen, Germany

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: www.gelsenkirchen.de

Country: Germany

Civilization: Early Modern, Modern

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

Horst Palace is located in the town of Gelsenkirchen in modern-day Germany. Its origins trace back to a farmstead established in the 11th century on an island surrounded by marshland formed by two branches of the Emscher River. The site developed through the medieval period as a defensive and administrative center within the region.

In the late 12th century, a wooden motte castle was built here by the noble family von der Horst to protect and secure the lands of Essen Abbey. By 1282, a stone castle had replaced the original timber structure, as recorded in a document granting Arnold von Horst permission from King Rudolf of Habsburg to fortify the nearby settlement and establish town rights. The castle’s chapel, dedicated to Saint Hippolytus, originally constructed in the 12th century, gained status as a parish church by around 1590.

The von der Horst family held the castle and its surrounding lordship from the 12th century onward. Initially independent rulers, they accepted the overlordship of the Archbishopric of Cologne in 1412 following legal disputes. After this submission, the castle became a fief under Cologne’s control, marking its integration into the archbishopric’s territorial structure.

A major transformation occurred between 1554 and 1578 when Rütger von der Horst commissioned the construction of a Renaissance-style castle. This replaced the earlier medieval building which had been destroyed by fire in 1554. Rütger was a prominent figure, serving as marshal for six Cologne electors and acting as governor of the Vest Recklinghausen region.

Ownership of the palace changed hands through marriage after 1582, passing to the von Loë family, and subsequently to the von der Recke family by 1607. In 1706, Baron Hermann Dietrich von der Recke sold Horst Palace to Baron Ferdinand von Fürstenberg. However, the Fürstenberg family never resided there permanently and allowed the property to fall into decline.

Throughout the 19th century, the castle suffered significant structural damage. Several wings and towers collapsed or were demolished between 1829 and 1854, yet the Fürstenbergs took care to preserve the elaborate Renaissance façade decorations, known as the “Stone Treasure.” In the early 20th century, the grounds found new use as a public recreational space featuring a restaurant and later a discotheque, activities which contributed further to the site’s deterioration.

In response to growing concern over the castle’s state, a citizens’ group formed in 1985 advocating for its preservation. Their efforts culminated in the purchase of Horst Palace by the city of Gelsenkirchen in 1988. Archaeological excavations beginning in 1990 revealed much about the castle’s construction history and uncovered numerous artifacts. From 1994 to 1999, restoration and partial reconstruction work transformed the palace into a cultural venue housing a museum, registry office, and event space. Nearby outer bailey buildings dating to 1856 were renovated and by 2013 adapted into a community center and district library, including a small museum dedicated to traditional printing.

Remains

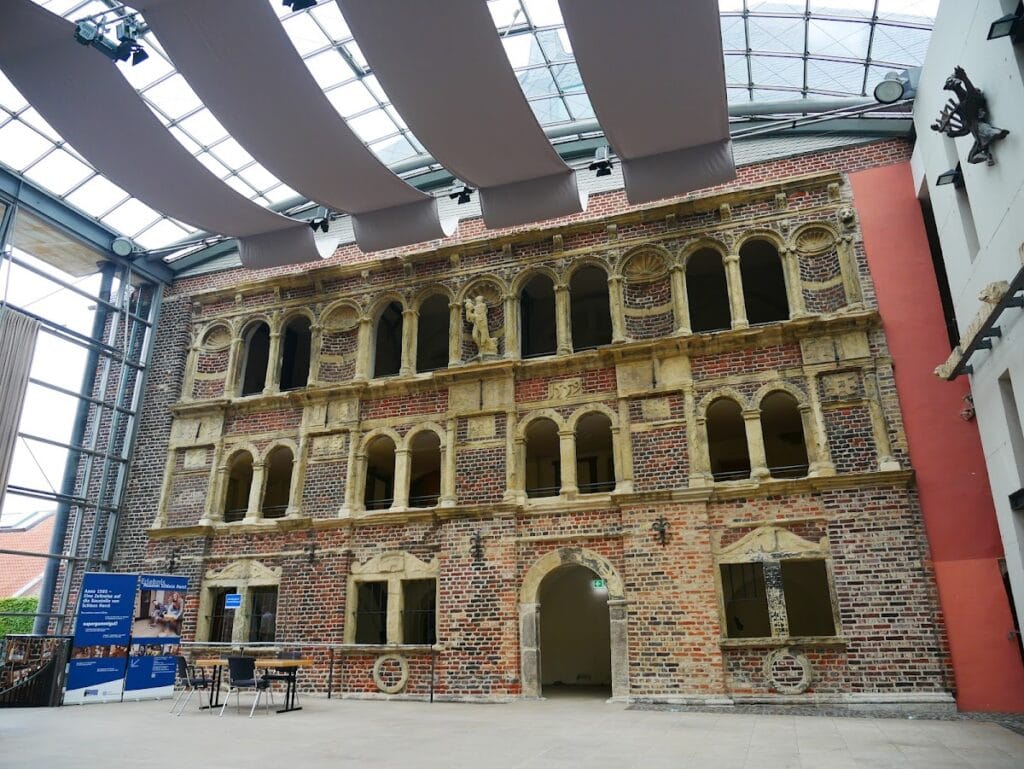

Horst Palace originally consisted of a large four-winged Renaissance complex measuring approximately 53 meters on each side, featuring square pavilion towers at the corners capped with distinctive “Welsh bonnet” shaped roofs. The construction combined red brick walls with light Baumberg sandstone used for window and door frames, friezes, and cornices. The entire exterior was once covered with white plaster accented by gilded sandstone elements and painted details simulating marble, creating a striking appearance.

The northeast and northwest wings, including the main entrance, survive as the most complete parts of the original structure. The northwest wing rises three stories tall with an ornate entrance portal, while the adjoining manor house wing retains two stories but matches the entrance wing’s height. The courtyard-side galleries of the entrance wing have vaulted ceilings with Renaissance-era ornamental and figurative wall paintings on the upper level, restored and visible today. The Knights’ Hall, dating from 1566 and situated in the manor house wing, remains intact and reflects Italian Renaissance architectural influence with its rusticated portal and elegant staircase.

At each of the four corners, the original pavilion towers were reconstructed up to courtyard level, with the north tower fully rebuilt to its historical height during restoration efforts in the 1990s. Across the site, vaulted cellars with characteristic cross vaults remain from all wings except the eastern and western tower basements. Today, the entire complex is enclosed by a 20th-century dry moat replacing the former wide and shallow moat fed by the Emscher River. A three-arched stone bridge connected the main island to the outer bailey, while a drawbridge controlled access at the outer gatehouse.

The entrance façade stands about 24 meters tall and features a three-story bay window richly decorated with carvings of caryatids (sculpted female figures), cartouches, and scrollwork crafted from Baumberg sandstone. Much of this decoration is reconstructed, replacing original pieces severely weathered by time. The façade is structured horizontally by two stone cornices and includes several types of windows framed by pilasters and columns in Tuscan and Ionic styles, interspersed with niches that once held statues, including a weathered 1.5-meter statue of the Roman god Saturn.

On the courtyard-facing side of the northeast wing, 19th-century demolitions removed parts of the façade, but later reconstruction used preserved fragments. A striking round-arched portal is framed by Corinthian columns and topped with a triangular pediment adorned with a lion’s head. The spandrels display sculpted herms (sculptural pillars with faces) and satyrs, and a Latin inscription from the Bible is carved into a stone band across the entrance.

Inside the ground floor, the castle houses a 16th-century Resurrection Fireplace depicting the biblical prophet Ezekiel’s vision of the resurrection of the dead. An oriel room features the partially restored Diana Fireplace, illustrating the goddess Diana punishing the nymph Callisto. These artistic elements highlight the Renaissance interest in mythological and religious subjects.

Archaeological investigations uncovered evidence of an advanced water and waste system, including a cistern to collect water, a well, and multiple levels of sewer shafts, demonstrating the castle’s sophisticated infrastructure. Numerous finds from the excavations reflect the high status of the castle’s historical occupants, including fragments of façade decoration, medallions portraying Roman emperors, intricately moulded tiles, and luxury items such as silver and ivory cutlery, cut stone vessels, fine ceramics, and Venetian glassware.

Together, these remains provide a rich, tangible record of Horst Palace’s architectural grandeur and the lifestyle of its noble inhabitants across several centuries.