Palazzo dei Normanni: The Oldest Royal Residence in Europe

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Very High

Official Website: www.federicosecondo.org

Country: Italy

Civilization: Early Modern, Medieval European, Modern, Phoenician

Site type: Civic

Remains: Palace

History

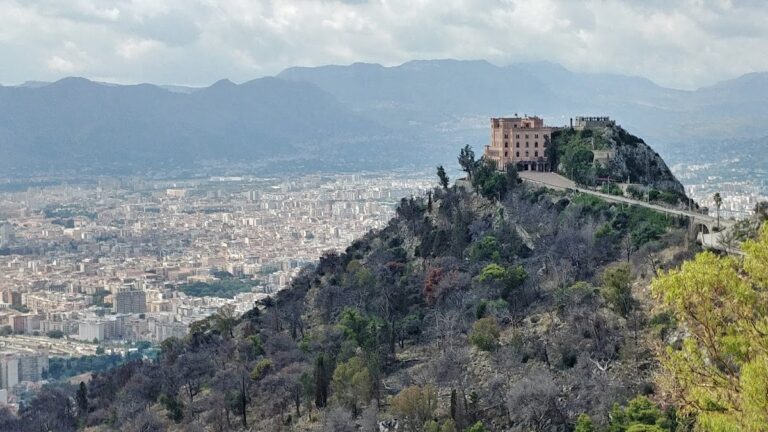

The Palazzo dei Normanni is located in Palermo, Italy, and stands as the oldest royal residence in Europe. Its origins date back to the Norman era, when it served as the primary seat of Sicilian kings. The site itself incorporates layers of settlement far older than the Normans, with foundations reaching back to the Phoenician-Punic civilization, active from the 8th to 5th centuries BCE.

Initially, the complex occupied a fortified position that the Romans conquered in 254 BCE. The Roman presence established important structural elements that would influence later construction. In 535 CE, control passed to the Byzantines, who maintained the site’s strategic importance. During the period of Arab domination between the 9th and 11th centuries, the settlement evolved into a royal residence known as al Qasr or Kasr—a term derived from Arabic meaning “castle” or “palace.” This phase marked a transformation that melded the fortified character with courtly functions.

With the arrival of the Normans, a clear architectural and functional distinction formed between two main areas: the upper castle, called Castrum superius or Palatium novum, located on a hill with Norman stylistic features, and the lower castle, known as Castrum inferius or Palatium vetus, which had been the Arab royal residence. Robert Guiscard extended the upper castle while Roger II contributed significantly in 1132 by constructing the central portion of the palace. His work included foundations that would house the famous Palatine Chapel and the Joharia Tower, cementing the palace’s role as a royal and administrative center.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the palace became a vibrant cultural hub. It attracted scholars, poets, musicians, and painters, and supported workshops specializing in silk production, goldsmithing, and textiles. This cultural efflorescence coincided with the palace’s significance as a seat of power for Norman and later imperial rulers such as Frederick II and Conrad IV.

The complex endured several episodes of conflict and destruction. In 1194, it suffered a major looting under Henry VI, and again in 1282, it experienced damage during the Sicilian Vespers uprising—a rebellion against Angevin control. In the revolutionary unrest of 1848, further harm was inflicted on the structure.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, when Sicily was under Spanish rule, the palace was restored and expanded. New Renaissance and Baroque elements were introduced, including the creation of the Maqueda Courtyard. Some medieval towers and churches were removed to make way for defensive bastions, reflecting evolving military needs. The palace became the residence of Spanish viceroys during this period.

Later, during the Savoy and Bourbon administrations, additional modifications were made. They included the construction of the grand Red Staircase and interior decorations with frescoes by artists such as Giuseppe Velasco and Olivio Sozzi, enriching the visual complexity of the palace’s interiors.

Following Italian unification, the complex was repurposed for military offices and various cultural institutions. Since 1947, it has served as the seat of the Sicilian Regional Assembly. Archaeological excavations carried out in the 20th century uncovered well-preserved Punic walls and other stratified remains beneath the palace, illuminating its ancient origins. In 2015, the Palazzo dei Normanni was recognized as part of the UNESCO World Heritage site entitled “Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale,” highlighting its unique historical and cultural layers.

Remains

The Palazzo dei Normanni has an inverted fork-shaped layout, with two wings extending southward that meet at the Palatine Chapel. This arrangement creates two significant internal courtyards. The Maqueda Courtyard is fully surrounded by Renaissance-style porticoes featuring two levels of loggias, showcasing the architectural influence of the Spanish viceroy period. Above it lies the Fontana Courtyard, positioned at a higher elevation, providing a further open space within the complex.

Four original Norman towers were constructed as part of the fortress. They include the Greca, Chirimbi, Pisana (also known as Santa Ninfa), and Joharia towers. Of these, only the Pisana and Joharia towers survive today. The Pisana Tower later hosted the Astronomical Observatory of Palermo, established in 1790, marking a scientific reuse of the structure. The Joharia Tower contains notable rooms such as the Sala degli Armigeri (Hall of the Armigers) and the Sala dei Venti (Hall of the Winds). The latter is characterized by a vaulted ceiling supported by columns, with mosaic decorations adding to its artistic appeal.

At the core of the palace lies the Palatine Chapel, consecrated in 1140 under Roger II. This basilica features three naves and is dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul. Its walls are lavishly covered with 12th-century Byzantine mosaics depicting Christ Pantocrator, evangelists, angels, and scenes from the Bible. The mosaics also include allegories related to the Norman court, integrating religious and royal iconography. The central nave’s wooden ceiling is noteworthy for its Arab stylistic influence, decorated with muqarnas—an ornamental form of stalactite vaulting—and Kufic inscriptions, an angular script of Arabic calligraphy.

Another distinguished space is the Sala di Ruggero (Roger’s Hall), crafted during the Norman period. It is richly adorned with gold mosaics illustrating scenes of hunting, exotic animals, and mythological figures. Imperial Swabian eagles, symbols of Frederick II’s reign, were later added to this room’s decoration.

The complex also houses the Sala d’Ercole (Hercules Hall) on the parliamentary floor, which serves today as the chamber of the Sicilian Regional Assembly. This room is decorated with frescoes by Giuseppe Velasco depicting the Labors of Hercules, integrating mythological themes within its artistic program. Adjacent rooms known as the Duca di Montalto rooms were once ammunition storage areas; they were converted into reception halls embellished with frescoes by Pietro Novelli and other artists.

Externally, the palace presents an eclectic mix of architectural styles. These range from Romanesque and Byzantine to Arab, Norman, Neo-Gothic, Chiaramontan, Renaissance, and Baroque influences. Features such as arches, ogival (pointed) windows, rusticated stonework, mullioned windows divided by narrow columns, and decoration using local lava stone reflect this diverse heritage. The northern façade is distinguished by the Porta Nuova, built under Emperor Charles V.

Beneath the palace, archaeological excavations have revealed remarkably preserved Punic walls dating to the 5th century BCE. Among these ancient features is a postern gate—a small secondary entrance used in antiquity. The underground areas also contain dungeons decorated with Viking-style ship graffiti, reflecting the complex history of occupation and cultural intersections over centuries.

Within the palace, monumental staircases connect the internal courtyards and different levels. A covered passageway known as the Via Coperta links the Palazzo dei Normanni directly to the adjacent Palermo Cathedral, demonstrating its close historical relationship with the city’s religious center.

The interior decoration is enriched by frescoes, mosaics, and paintings by notable artists including Giuseppe Patania, Pietro Novelli, Giuseppe Velasco, and Salvatore Gregorietti. Their works depict a range of themes from biblical narratives and allegorical figures to historical portraits of viceroys and monarchs, contributing to the palace’s layered visual narrative.

Today, the site also accommodates military offices in the west wing, continuing its longstanding role as a seat of authority and administration. The mixture of archaeological remains and diverse architectural styles reveals the palace’s continuous adaptation and importance from antiquity through the medieval and modern periods.