Castle da Rocha Forte: A Medieval Fortress in Santiago de Compostela

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 3.8

Popularity: Low

Country: Spain

Civilization: Medieval European

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

The Castle da Rocha Forte is a medieval fortress located in the municipality of Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was built around 1240 by the archbishop Juan Arias and served as the residence of the archbishop and the cathedral chapter, asserting ecclesiastical authority over the surrounding territory.

The first written mention of the castle dates from 1255 in connection with the capitular constitutions issued by Archbishop Juan Arias. In the early 14th century, the castle was damaged during local conflicts, notably the uprising led by Alfonso Suárez de Deza, a noble of the Deza-Churruchaos family. This unrest is recorded in the document known as the “Hechos de Don Berenguel de Landoria.” Following these events, the castle was rebuilt and reinforced.

Archbishop Berenguel de Landoria, who began his tenure in 1318, made the castle a place of refuge during a turbulent era. Most infamous was the event known as the “Day of Wrath” on September 16, 1320, when eleven city representatives were treacherously killed within its walls during negotiations, further embedding the castle’s role in local power struggles.

Subsequent archbishops, including Lope de Mendoza, undertook further modifications. Through the 14th and into the mid-15th century, the castle remained a vital defensive and administrative center. However, conflict persisted. In 1458, Archbishop Rodrigo de Luna’s forces endured a siege by a noble-led brotherhood defending civic liberties. Despite royal orders to end the siege, the castle held out until a reconciliation was reached in 1459.

During the 1450s and 1460s, resentment against the castle grew among local peasants due to abuses by archbishop’s soldiers, such as theft, kidnapping, and violence. This hatred culminated in the Great Irmandiña Revolt of 1467, when roughly 11,000 insurgents attacked and destroyed the castle to its foundations, making it one of the earliest fortresses brought down during this popular uprising. Unlike many other castles damaged during the revolt, this fortress was never rebuilt.

After its destruction, stones from the castle were repurposed in various constructions, including the now-lost castle of Pico Sacro and parts of Santiago de Compostela, possibly even the cathedral itself. In the 20th century, the ruins experienced further harm due to railway construction near the site. Since 2001, excavations led by the Santiago City Council and the University of Santiago de Compostela have aimed to study, conserve, and develop the area as an archaeological park.

Remains

The castle’s ruins occupy roughly 4,000 square meters on a small promontory called Rocha Vella, near the meeting point of the Vilar stream and the Sar river. Unlike typical medieval castles built on high ground, this fortress was situated in a valley close to water, controlling access to Santiago from the south and guarding important pilgrimage and trade routes from the sea.

Its defensive layout comprised three concentric enclosures. Today, parts of the outer wall remain in the southeast, preserving about 40 meters of its length. The inner contour is more complete, including central structures believed to be the keep, or main tower. This keep was a four-story tower surrounded by nine circular towers, each with crenellations—crenellations are the notched battlements seen atop castle walls for defense. These towers included two named Santa Eufemia and Torre Nova, strategically placed at corners and along key walls. The main defensive complex featured gates, posterns (small secondary doors), drawbridges, moats (one containing water permanently), and barbicans—fortified outposts guarding main entrances—resulting in an arrangement likened to a small enclosed city.

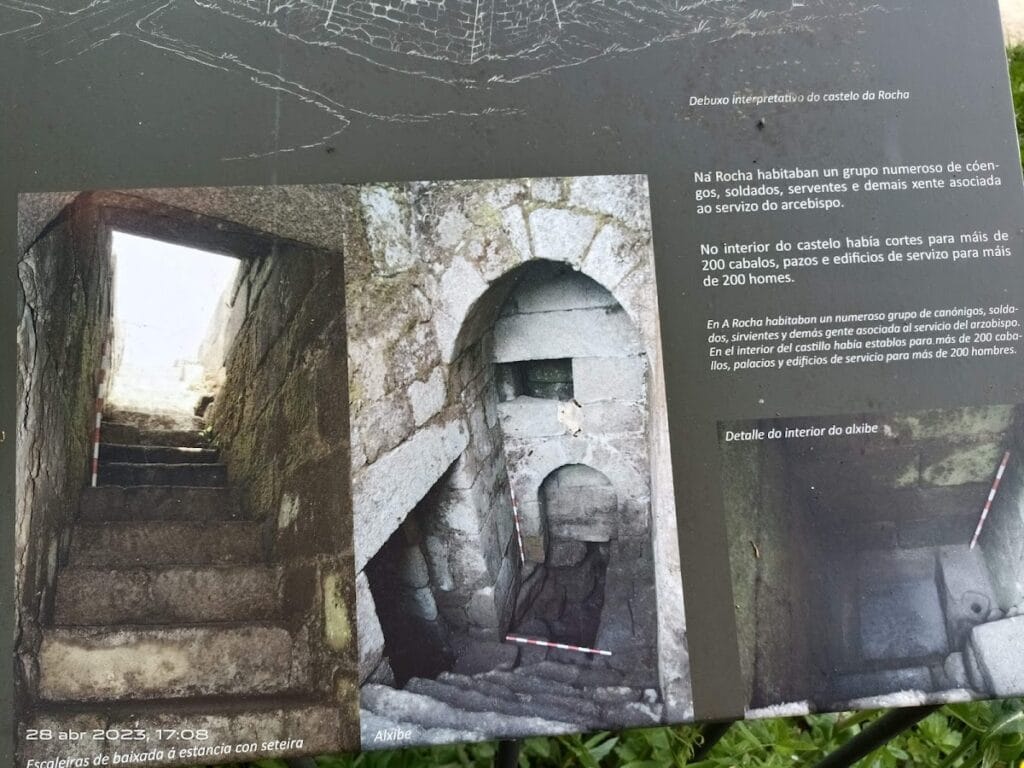

Next to the keep lay a vaulted chapel dedicated to Santa Eufemia, reflecting the castle’s religious ties. Below ground, two vaulted chambers have been identified, accessible by stepped entrances, although much remains to be explored. Archaeological excavation uncovered a stone masonry well, 3.7 meters deep, still holding water, along with an advanced drainage system to manage runoff outside the walls.

Among the recovered architectural elements are Gothic capitals (the tops of columns), carved moldings, window grilles known as celosías, and column shafts with decorative plant motifs. Some walls show traces of lime plaster, suggesting a finished interior appearance. The building material throughout is finely cut sandstone blocks fixed together with lime mortar, demonstrating skilled craftsmanship.

Excavations also revealed a trapezoidal bastion on solid rock within the southeast barbican measuring nearly 36 meters long and up to 4.5 meters high, well preserved and highlighting the fortress’s formidable defenses.

Finds from the site include medieval pottery both local and imported—such as Sevillian and Manises ceramics—horse shoes, bronze fittings for clothing and furniture, animal bones, and fragments of glass. Large collections of stone projectiles called bolaños, some shaped to fit siege engines like trebuchets, confirm the castle experienced serious military assaults. Weapons uncovered comprise many arrowheads of the Bodkin type, known for armor-piercing qualities, and two possible swords currently under study.

Coins numbering 39 were also discovered, mostly dating from the reign of Henry III of Castile (1390–1404), including several denominations like blancas de vellón, obols, novens, and cornados, indicating the castle’s long active period.

The northern side of the castle remains partially obscured today because a railway line crosses the site, contributing to its fragmented state. Nevertheless, systematic archaeological work continues to preserve and interpret the remains, offering insight into this historically significant medieval fortress.