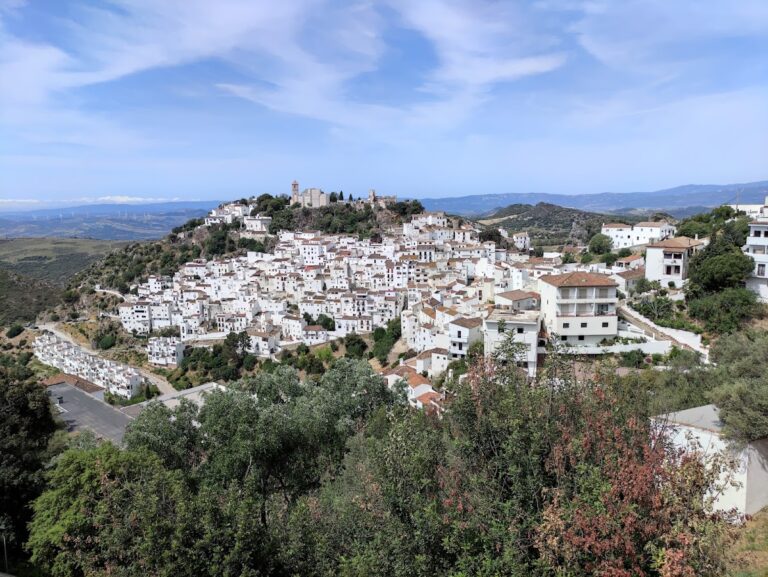

Castillo de Montemayor: A Historic Fortress in Benahavís, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Low

Official Website: pueblos-andaluces.blogspot.com.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Medieval Islamic

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

The Castillo de Montemayor is a fortress located in the municipality of Benahavís, Spain. Its origins trace back to the Islamic period of the Iberian Peninsula, though artifacts such as Roman coins found at the site suggest an even earlier occupation dating to Roman times. This broad historical layering establishes the castle as a long-standing strategic stronghold in the region.

During the early Middle Ages, the castle was documented by notable 10th-century Arab historians including Ibn Hayyan and al-Razi. They emphasize the fort’s importance as a defensive position tied to the rebel leader Umar Ibn Hafsun, a figure who resisted central authority in Al-Andalus. Initially connected to the fortress at Bobastro, Montemayor later became part of the domain governed from Marbella after Bobastro’s fall.

In the 11th century, the castle was an active participant in territorial disputes between rival Muslim kingdoms, specifically the Idrisid taifa of Málaga and the Hamudí taifa of Algeciras. These conflicts marked an era of fragmentation and competition following the decline of centralized Caliphate power. References to the castle continue into the 14th century, appearing in Maghrebi administrative records that place Montemayor within the district of Málaga, indicating its sustained regional relevance.

The stronghold served the rural Andalusi population primarily as a site for defense and surveillance over several centuries, roughly spanning the 8th through the 15th century. In 1485, following the fall of Ronda, the castle surrendered to Castilian forces during the Reconquista, entering a new phase of Christian rule. Subsequently, it was abandoned as a permanent military installation but found renewed use during the Morisco revolt of 1568, when it acted as a refuge for rebellious Muslims resisting Christian authorities.

In the 19th century, the castle regained military significance during the Peninsular War, when Spanish forces utilized it against Napoleon’s invading troops. Its elevated position and historical role as a lookout point made it valuable once again in this period of armed conflict. Today, the Castillo de Montemayor stands protected under Spanish heritage laws established in 1949 and reinforced in 1985, a recognition of its enduring historical and cultural importance.

Remains

The Castillo de Montemayor is positioned atop a pyramidal mountain reaching 579 meters in elevation near the Sierra Palmitera, a vantage point that allows commanding views across the surrounding landscape. Its design features up to three concentric rings of defensive walls, with the two inner enclosures remaining the most intact. These walls are constructed entirely from masonry and are strengthened by a series of small prismatic towers. Notably, two of these towers have been altered over time into semicylindrical forms, while one retains a trapezoidal shape, showcasing variations in defensive architecture.

The fortress is defined by its double enclosure, which incorporates thick masonry walls and square defensive towers known as “cubos.” Within its walls, several cisterns (locally called aljibes) provided water storage critical for withstanding sieges. One such cistern, located inside a tower, is divided into two parts—a rectangular compartment and a trapezoidal one—linked by a small window between them. The cistern’s interior walls bear a coating of hydraulic plaster with traces of red ochre pigment, and remnants of vaulted ceilings are still visible, pointing to the care taken in its construction.

Access to the castle was granted through two main gates punctuating the outer walls: a larger entrance facing east and a smaller gate opening to the south. Inside the fortress, archaeological remains include fragments of rooms and the collapsed structures that once connected the primary enclosure to the secondary defensive areas, providing insight into the castle’s internal layout and functions.

Dating evidence for the castle’s occupation comes from ceramic fragments found on site, which range from the 10th to the 14th centuries. These finds have helped researchers reconstruct the castle’s plan and understand its development through the medieval Islamic period. Over time, some sections of the outer walls and their accompanying towers have fallen into ruin or disappeared, yet the visible remains continue to bear witness to the castle’s long-standing role as a military and surveillance site in southern Spain.