Dendera Temple Complex: An Ancient Egyptian Religious Site in Qism Qena, Egypt

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: egymonuments.gov.eg

Country: Egypt

Civilization: Egyptian, Greek, Roman

Site type: Religious

Remains: Temple

History

Dendera Temple Complex, Qism Qena, Egypt, was created by the ancient Egyptian civilization.

Origins of the site reach back to about 2250 BCE, when construction may have begun under Pharaoh Pepi I and continued under Merenre Nemtyemsaf I; by its height the settlement supported thousands of residents and functioned as the administrative center for the sixth nome of Upper Egypt, positioned south of Abydos. Archaeological evidence also indicates a place of worship here during the New Kingdom, with a temple attested around 1500 BCE during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

The complex continued to evolve through later native dynasties into the Late Period. The earliest surviving standing building on the site is a mammisi, or birth-house, attributed to Nectanebo II (reigned 360–343 BCE). During the Ptolemaic era the major rebuilding and decoration campaign culminated in the construction of the principal sanctuary beginning in 54 BCE under Ptolemy XII Auletes. Reliefs from the Ptolemaic kings include images of members of the Macedonian dynasty such as Cleopatra VI and Cleopatra VII shown alongside her son Caesarion.

Under Roman provincial rule the temple receives further modification and adornment. A columned hall was executed during the reign of Tiberius and later emperors carried out additional work: Domitian and Trajan are recorded as patrons of particular gates and decorative programs, and reliefs of Roman emperors appear in Egyptian dress. A Roman-period mammisi shows emperors such as Trajan portrayed making offerings in traditional pharaonic form. In the modern era the site has been the subject of repeated conservation, with organized restoration beginning in 2005, interrupted in 2011, and restarting in 2017; cleaning and repainting of major halls and scenes were underway by 2021. More recent fieldwork in March 2023 brought to light a carved limestone sphinx that scholars identify with the Roman Emperor Claudius.

Throughout its long life the complex retained its primary association with the goddess Hathor and related cults, serving both ceremonial and healing functions tied to those deities.

Remains

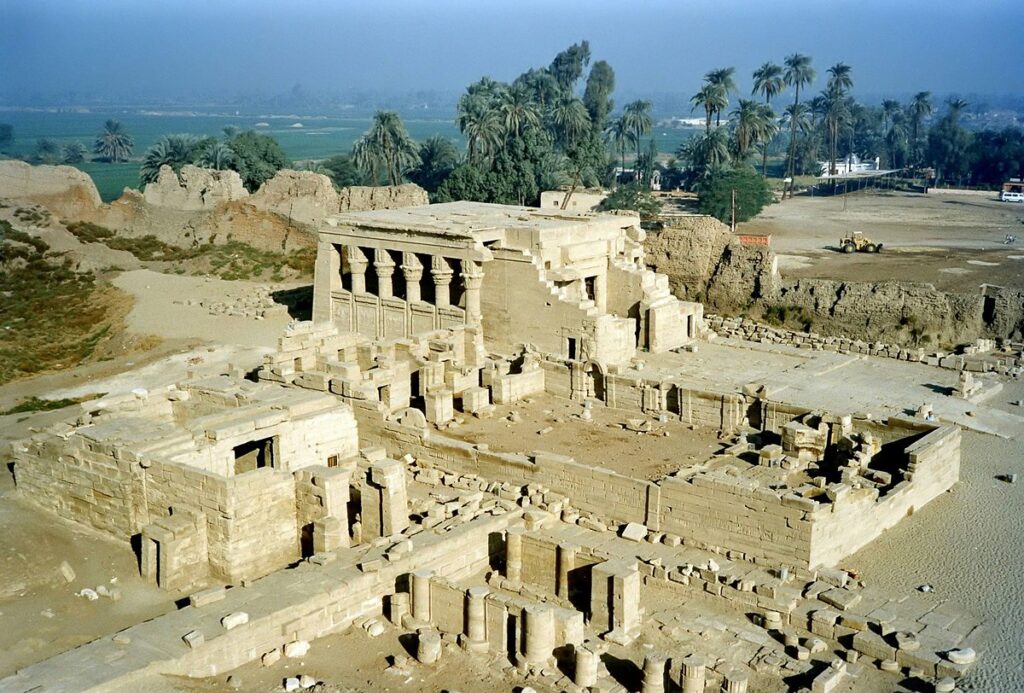

The Dendera complex spreads behind a substantial enclosing wall built of mudbrick and contains a sequence of temples, chapels, service buildings and open spaces laid out over a broad site, reflecting construction and reuse from the Middle Kingdom through Roman times. Stone and painted reliefs sit alongside mudbrick revetments, and buildings from different periods stand in close relation, showing how the place was continually adapted for ritual and practical needs.

Dominating the ensemble is the Temple of Hathor, begun in the late Ptolemaic period, its fabric largely hewn from dressed stone and covered with sculpted decoration. Work on its internal columned hall, a hypostyle hall (that is, a large room supported by many columns), dates to the time of the emperor Tiberius. The temple’s walls preserve images of Ptolemaic rulers, including scenes that show Cleopatra and her son, and panels that honor Hathor and a group of ten deities associated with her. Painted surfaces have been the subject of recent cleaning and color restoration campaigns.

Beneath the temple lie a series of underground storage and ritual rooms, commonly called crypts, arranged as twelve chambers carved into the bedrock and used to hold ritual vessels and cult equipment. These chambers bear carved and painted offerings scenes that, in some cases, record gifts by rulers such as Pepi I and later by Ptolemy XII Auletes. One chamber, reached through an opening in the so-called Flame Room floor, leads into a narrow passage whose walls depict the objects once kept there.

A prominent sculpted ceiling panel known as the Dendera zodiac, dated to the first century BCE, originally adorned the temple’s roof or ceiling; it represents familiar constellations and star signs and was removed from the site in 1820 and taken to the Louvre, while a copy now occupies its former place at Dendera. Other reliefs within the sanctuary show the god Harsomtus emerging as a serpent from a lotus flower, set inside oval emblems called hn, a term used for those container-shaped frames and here possibly evoking the womb of the sky goddess Nut.

Access to the roof is provided by a long, ceremonial stair whose worn treads and accumulated material have given it a distinct appearance in the modern record, and which is decorated with ritual scenes along the ascent. The building program also included specialized chapels and smaller shrines where portable cult images were housed and paraded during festivals; barque shrines were constructed to hold the sacred boats used in those processions.

Near the main temple are structures associated with birth and healing rites. Multiple mammisis, the Egyptian term for a temple complex’s birth-house dedicated to the divine birth of a god, stand at the site; the earliest preserved example dates to Nectanebo II. A later Roman mammisi, attributed to the time of Trajan and extended under Marcus Aurelius, presents imperial figures rendered in Egyptian style making offerings to local gods such as Hathor and Ra-Harakhte. Close by, a sanatorium served ritual and therapeutic functions, operating in a manner comparable to Roman bathing complexes for healing purposes.

The complex’s open spaces include a sacred lake that supplied water for rites and household needs, while civic and ceremonial approaches are marked by named gateways and freestanding structures. Two monumental gateways are associated with Domitian and Trajan, each carrying their own carved programs, and a Roman kiosk and a basilica-like building form part of the later architectural accretions. Smaller barque chapels and service buildings supported festival activity and the cult’s daily requirements.

Stone sculpture and inscriptions continue to emerge from the site. In March 2023 excavators uncovered a limestone sphinx with a royal nemes headcloth tipped by a uraeus cobra, a find attributed to the emperor Claudius; the piece is carved in local stone and represents the way Roman rulers were sometimes depicted in Egyptian iconography. Conservation work recorded in recent years has included cleaning, consolidation and repainting of important halls and decorative scenes, leaving many reliefs and architectural elements in a state of active preservation or partial restoration.