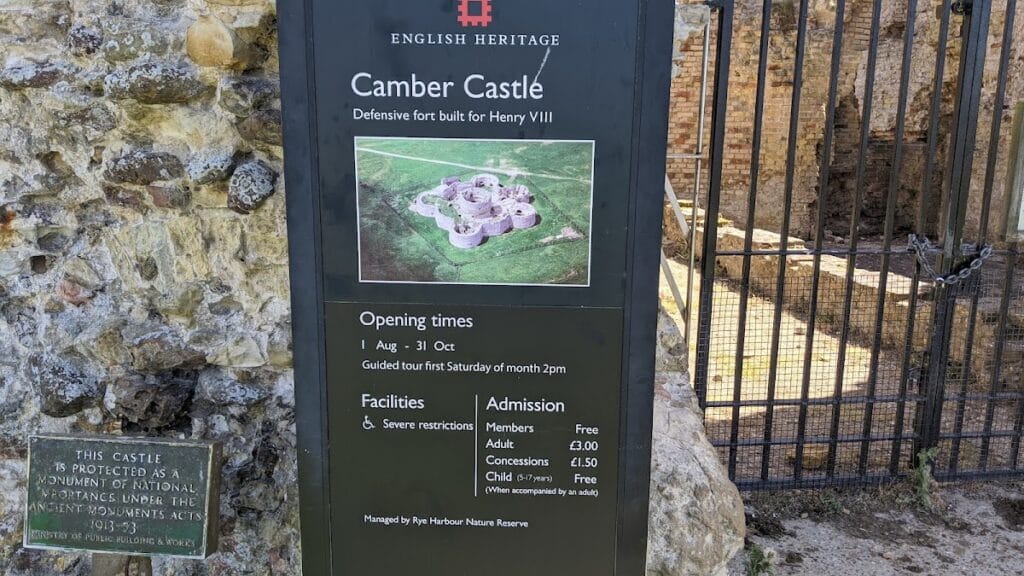

Camber Castle: A Tudor Artillery Fort in England

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Low

Official Website: www.english-heritage.org.uk

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Early Modern

Site type: Military

Remains: Fort

History

Camber Castle is situated near the town of Winchelsea in England and was built by the English during the early 16th century. Its original purpose was to protect the Sussex coastline against potential attacks from France.

Construction began between 1512 and 1514 under King Henry VIII, who commissioned a small round artillery tower known then as Winchelsea Castle. This initial structure was intended to guard the anchorage at the Camber and the nearby entrance to Rye Harbour. The fortification was modest, designed primarily as a vantage point for artillery to oversee and defend the harbour approaches.

In 1539, as tensions with France and Spain escalated, Henry VIII ordered a significant expansion of the castle. Moravian engineer Stefan von Haschenperg led the rebuilding to transform the tower into a more formidable concentric artillery fort. The new design included a central keep surrounded by four rounded bastions and a circular entrance bastion. Between 1542 and 1543, extensive and costly modifications were carried out to address recognized flaws in the design and strengthen the fort’s defensive capabilities.

Initially, Camber Castle was equipped with 28 brass and iron artillery pieces and maintained by a garrison of 28 men under a captain. There is some indication the castle may have seen action during a French attack in 1545, although details of this engagement remain limited. However, as the centuries passed, natural silt buildup and coastal changes caused the harbour to recede, leaving the castle further inland and diminishing its strategic importance.

By the late 16th century, changes in military technology favored forts with angular bastions, making Camber’s rounded designs less effective. Additionally, improved relations and peace with France reduced the immediate threat. The castle stayed in use until 1637, when King Charles I ordered its closure.

During the English Civil War beginning in 1642, forces supporting Parliament partially dismantled Camber Castle to prevent it from being used by Royalist troops. The fort saw no Royalist occupation during the 1648 conflict. Afterward, the structure fell into ruin.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the ruins became a site for leisure and inspiration. Notably, the artist J. M. W. Turner depicted the castle in his works. Several proposals over the following centuries sought to repurpose the structure, including conversion into a Martello tower or later into a golf clubhouse, but none were realized.

During the Second World War, the British military repurposed the site, likely establishing an early warning post equipped with searchlights for anti-aircraft defense. The surrounding area saw additional military training and the creation of decoy installations.

Interest in the castle’s archaeology grew during the mid-20th century. Between the 1950s and 1980s, excavations and surveys led by Martin Biddle deepened understanding of the site. The British state took on guardianship in 1967, purchased the castle in 1977, and English Heritage reopened the site to the public in 1994. Today, Camber Castle remains a rare and well-documented example of an unaltered Device Fort from the Tudor period.

Remains

Camber Castle forms a roughly concentric artillery fortification covering about 3,000 square meters and rising up to 18 meters tall. Its surviving structures reflect three main stages of construction spanning from the original artillery tower built between 1512 and 1514 through expansions completed by 1544. The design centers on a fortified keep surrounded by a series of bastions and curtain walls arranged in an octagonal plan.

The earliest part of the castle is the original circular artillery tower, or donjon, measuring 20 meters across and standing 9 meters high. Built primarily of fine yellow sandstone, this round tower formed the core around which later defences were developed. In subsequent building phases, construction used a combination of yellow and grey sandstone, with quality stone imported from Caen in Normandy for detailed elements. The walls’ cores contained rubble made of ironstone, siltstone, and sandstone quarried from nearby cliffs, highlighting a mix of local and imported materials.

The entrance bastion evolved significantly over time. Initially a square, single-story building measuring 15 by 10.5 meters, it was later extended forward by 9 meters and reshaped into a circular bastion. This section gained an additional floor, creating separate functional spaces: the ground floor housed administrative rooms and possibly living quarters for the deputy captain, while the upper floor contained more elaborate chambers featuring large windows, fireplaces, and a private garderobe, a medieval toilet. Much of the upper floor has deteriorated, leaving limited remains today. A distinctive feature in the captain’s chamber was a German cocklestove decorated with images of Landsknecht soldiers and notable Protestant German leaders; only fragments of this stove survive.

At the heart of the castle is the central keep, which incorporates parts of the original tower’s walls about 6.7 meters in thickness. These walls are robust, measuring over three meters in thickness, and include ten ground-level gunports that were later sealed. The keep originally had a flat roof that was converted to a pitched roof during the final building phase. Inside the keep is a brick-lined well crucial for water supply, as well as two small fireplaces not meant for cooking. Windows on the first floor had bars and shutters for security but were not designed as gunpositions. Encircling the keep, now partly ruined, is a vaulted underground passage approximately 1.9 meters high with radial covered corridors extending to each of the surrounding bastions, allowing protected movement within the fort.

Enclosing the keep is a cobbled courtyard that separates the central core from the outer defences. Located in the northwest corner of this courtyard is an additional well. From the entrance bastion, underground tunnels once extended beyond the castle walls, possibly serving as escape routes or for launching surprise attacks on besiegers.

The outer defences consist of an octagonal curtain wall linked by four two-storey towers known as “stirrup” towers. These towers are roughly 6 by 6.2 meters internally, with solid walls around 0.8 meters thick. Their fronts are flat, while their rears curve inward. This curtain wall was first constructed in the second building phase and later strengthened with a thickened exterior facing over 2 meters deep, which includes openings for guns and parapets for defenders.

Running along the interior face of the curtain wall was a two-storey gallery providing barracks space for soldiers. Today, only the ground floor remains, illuminated by windows that open onto the courtyard. The four bastions added in the last phase of construction are about 19 meters wide inside and extend 12 meters outward from their adjacent stirrup towers. They feature thick walls around 3.6 meters in thickness. Each bastion contains a single internal gun room topped by a heavily fortified gun deck, except the western bastion, which functioned as a kitchen with two circular ovens and a cooking range.

In the early 1600s, an earthwork called the Rampire was built along the southern and southeastern defences. This embankment partially covers the south stirrup tower and bastion and blocked many of the gunports with stone, reflecting a later phase of fortification changes.

Further defensive features include a raised embankment about 1.8 meters high running around the south and east sides of the castle. Originally, this was topped by a stone wall protecting against coastal approach, as the sea lay much nearer in earlier centuries. Remains of a raised causeway connecting the castle to the mainland survive but have become largely buried over time.

The castle’s fabric displays a diverse range of building materials. Stone was sourced from the dissolved Winchelsea monastery and nearby quarries at Fairlight and Hastings, with higher quality stone brought from Mersham in Hampshire and from Normandy. Timber came from several local sites including Udimore, Appledore, and Knell. Chalk, used as a binding material in lime mortar, was transported from Dover. Over half a million bricks were manufactured on-site during the castle’s construction, illustrating the scale of building activity involved.

Originally, Camber Castle mounted between 26 and 28 artillery pieces, combining brass and iron guns such as demi-cannons, culverins, demi-culverins, falconets, and wrought-iron weapons including portpieces and bases. By the late 1500s, the number of guns was reduced to about nine or ten smaller pieces, with brass guns favored for their quicker reload times and improved safety for the crew.

While the castle’s rounded bastions and high walls may appear impressive, this shape created dead zones where defenders could not target attackers. Additionally, the rounded design presented larger targets compared to contemporary European forts that employed angular bastions for better fields of fire and coverage. The internal layout was complex, making movement within the fort challenging for its occupants. Despite these drawbacks, Camber Castle preserves an important example of early Tudor coastal defence strategies.