Stone Lion Statue, Hamedan: An Ancient Guardian of the City Gate

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Country: Iran

Civilization: Greek

Site type: Civic

Remains: Monument

History

Stone Lion Statue, Hamedan municipality, Iran, has an ancient origin that scholars attribute variously to Median, Parthian, or Hellenistic hands.

Origins and early role: The monument began life more than two thousand years ago and originally stood as one of two monumental felines that flanked a city entrance. Together the pair guarded the gateway locally remembered as the Lions’ Gate; during the early centuries of Islamic rule the portal was called bâb ul-asad, an Arabic name meaning the lions’ gate. Placed to overlook the approaches, the sculptures served a protective and commemorative role for the urban entrance they marked.

Late antique and medieval episodes: The statue’s long history includes damage associated with the Arab conquests of the seventh century, a period when many urban sites in the region experienced military and political change. In 931 AD, when forces of the Deylamid dynasty took control of the city, the gate complex was deliberately demolished. The Deylamid commander Mardāvij attempted to move one of the lion figures to the regional capital Ray; when that effort failed he ordered them broken. One of the two sculptures was reduced to rubble, while the other was only partly destroyed and came to lie on its side for centuries.

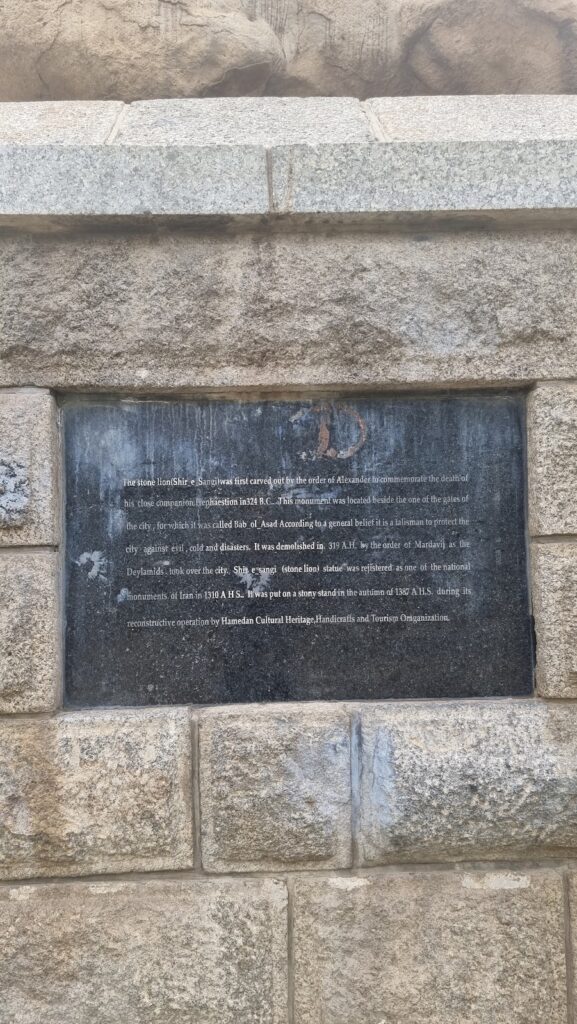

Scholarly interpretation and modern care: In 1968 the scholar Heinz Luschey published an influential study that compared this lion with a well-known Hellenistic memorial at Chaeronea and argued the sculpture belonged to the Hellenistic period, proposing it was set up on the orders of Alexander the Great to mark the death of his companion Hephaestion in 324 BC. This reading has been acknowledged by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization as a viable interpretation. After centuries of exposure and partial ruin, the remaining lion was lifted and stabilized in 1949, an intervention that brought the displaced monument back onto its hill and preserved it as an element of the city’s material past.

Remains

Overview: The surviving element at the site is a single monumental lion carved from one block of stone, originally paired with a matching figure to frame an important city gate. The ensemble was set upon a raised position known locally as Lion Hill, or Kuh-e Shir, so that the sculptures dominated nearby terrain and served as visible markers for the southern approach to the city.

The lion sculpture: The statue is a solid, robust carving that emphasizes mass and presence, a style often linked with Parthian or Median artistic vocabulary, though other scholars have seen Hellenistic affinities. Hellenistic refers to the era and cultures influenced by Greek rule after the conquests of Alexander the Great. The figure was hewn directly from a single stone block, with tool-work still readable in areas around the mouth and eyes despite extensive surface erosion. Traces of once-sharper musculature, facial carving, and decorative work remain in worn form; those finer details were softened by weathering and by the partial dismantling it suffered in the tenth century.

Alterations and condition: Historical records and later interventions document a violent episode when the gate was destroyed in 931 AD and one of the pair was smashed beyond repair, while the surviving lion was toppled and left on its side. In the mid-twentieth century conservators raised the fallen statue and fitted a replacement support for a broken limb, work that stabilized the piece and returned it to an upright display. Today the lion stands near the city’s southern entrance, on the hill from which it once signaled the gate, and survives as a restored, though visibly weathered, stone monument. Oral and written traditions preserve its association with the former Lions’ Gate and with the local toponym Kuh-e Shir, linking the carved animal to the long story of the city’s defenses and changing rulers.