Bazira Ruins: An Ancient Fortified Town in Barikot, Pakistan

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Very Low

Country: Pakistan

Civilization: Greek, Parthian

Site type: City

History

Bazira Ruins (Bazira Kandarat) in Barikot, Pakistan began as a Chalcolithic settlement and later developed into a fortified town, with successive major contributions from regional and Hellenistic-period polities.

Human occupation at the site stretches back to about 1700 BC, when a protohistoric village was established. Over many centuries this small settlement grew and by the mid-first millennium BC had the characteristics of an urbanized, fortified place. In the centuries around 500–250 BC the local culture shows signs of Achaemenid influence and then a phase of regionalization associated with the Assakenoi tribal group.

The site figures in the campaigns of Alexander the Great, whose forces reached the citadel in 327 BC; archaeological evidence indicates a pre-Buddhist shrine from that era which was later transformed. In the following decades Bazira entered the orbit of imperial South Asian power, and around 250 BC, in the period of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, an apsidal Buddhist temple (an apsidal building has a semi-circular end) and an Indian-style stupa were established and used by local communities.

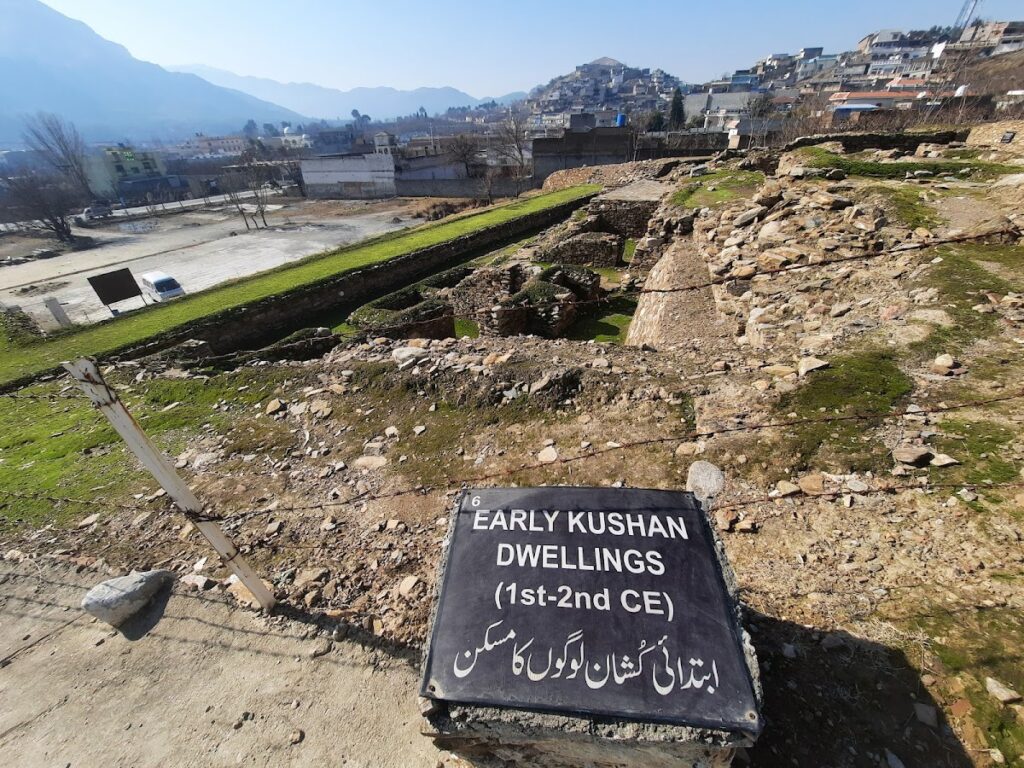

Bazira remained active through the Indo-Greek period. Archaeological finds associate the site with Hellenistic material culture and with Menander I in the mid-second century BC, whose silver coin was recovered there. Between about 200 and 100 BC the settlement was enclosed by a substantial defensive circuit, and a burial dated to c. 130–115 BC relates to that phase of fortification. Afterward the town experienced Saka and Parthian control around 50 BC to 70 AD, and then Early and Late Kushan phases from about 70 to 250 AD. Earthquakes together with the decline of Kushan authority led to the abandonment of the Buddhist complex in the third or fourth century CE. Centuries later, around 700 AD, a temple was erected on the Ghwandai mound during the Hindu Shahi period and remained in use until roughly 1000 AD. Modern archaeological investigation has been carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission since 1984, following initial work by Giuseppe Tucci and subsequent researchers, which has exposed layered occupation and many recovered objects.

Remains

The excavated layout shows a town of roughly twelve hectares with a higher central acropolis, surrounded in the Hellenistic era by a massive defensive wall punctuated by large rectangular bastions. These fortifications belong to the Indo-Greek phase of construction after 200 BC and were revealed during stratified excavation; a burial closely associated with the wall has been radiometrically dated to about 130–115 BC. The defensive circuit and the acropolis survive in archaeological contexts uncovered and recorded by the Italian mission.

A prominent religious complex on the site is an early Buddhist apsidal temple, dated to about 250 BC and associated with an Indian-style stupa. The term apsidal describes a building ending in a curved, semi-circular recess. Excavations show this sanctuary was adapted from an earlier non-Buddhist shrine that can be linked to the time of Alexander’s siege in 327 BC, and the temple remained in use through the Indo-Greek period until its abandonment in the third or fourth century CE. Finds from the temple include coins (among them a silver coin of Menander), an onyx seal bearing a Hellenistic engraved image, and monumental inscriptions written in Kharosthi, the local script used in the region.

The material culture recovered at Bazira highlights sustained Hellenistic connections alongside local traditions. Pottery includes fish plates and a fine polished black ware that imitates Attic Greek models, as well as bi-carinated and incised local types and many small miniature vessels. The onyx seal contains an intaglio, a small gem engraved with a design, and carries a Kharosthi inscription. These objects together document commercial and artistic exchange and appear in situ within domestic and cultic contexts.

Sculptural and carved remains illustrate religious diversity and stylistic blending. Excavations yielded a large green schist statue of the young Siddhartha on the horse Kanthaka, a carved stupa ornament with two lions, and a figurine of a deity holding a wine goblet and a severed goat head, a motif interpreted either as the Greek god Dionysus or as a local divine figure. These stone works were uncovered within the sequence of occupation and are preserved in the excavated assemblage.

Domestic quarters and craft areas have also been exposed, revealing houses, workshops, and everyday objects. Archaeologists found toy-carts, stone tools, glass fragments, and workshop debris alongside pottery and small vessels, indicating household and artisanal activity through successive cultural phases. On the Ghwandai mound the later Shahi-period temple, erected around 700 AD and attested in a Hindu Shahi inscription now in the Lahore Museum, represents a late cultic phase whose remains were documented during the mission’s fieldwork. Overall, stratified excavation has left a rich record of architecture, inscriptions, sculptures, and portable finds preserved in their archaeological contexts.