Tinnumburg: A Historic Circular Fortification in Westerland, Germany

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Official Website: de.wikipedia.org

Country: Germany

Civilization: Medieval European

Site type: Military

Remains: Fort

History

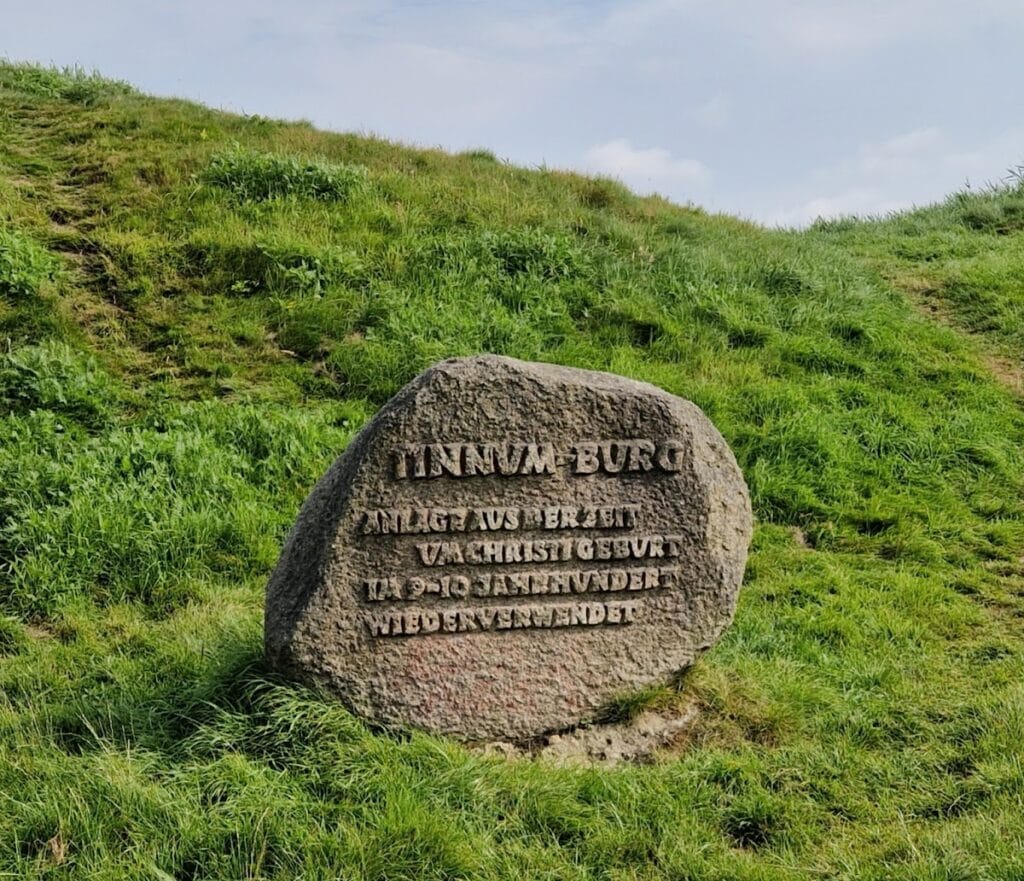

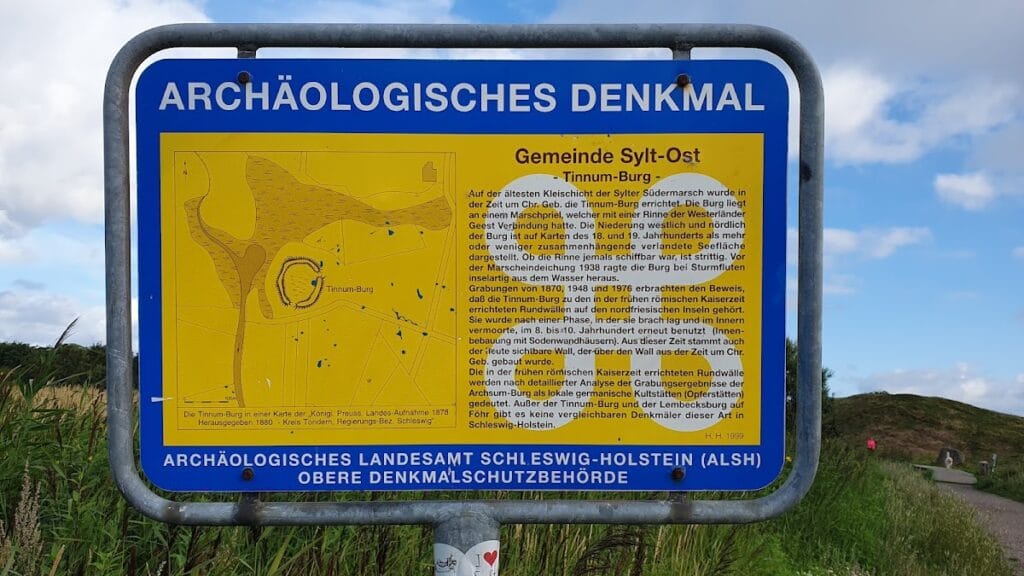

The Tinnumburg is a circular fortification situated near Tinnum in Westerland, Germany. It was originally constructed around the beginning of the first century CE by early Germanic peoples during the Roman Imperial period. At this time, it likely served not only as a defensive structure but also as a site of religious or ritual significance, as suggested by archaeological evidence pointing to its use as a Germanic cult location.

Following its initial period of use, the site eventually fell into disuse and became overgrown by marshland. This abandonment lasted for several centuries, but between the eighth and tenth centuries, the fort saw renewed activity. During this later phase, inhabitants built houses with sod walls within the enclosure, indicating a shift toward a more domestic or settlement-oriented use. The location’s connection to the surrounding waterways also became important as access to the sea was maintained through a tidal creek, known as Prielstrom, and a nearby lake called Döplem. This water link suggests the fort was integrated into Viking Age maritime routes.

Around one kilometer from the ring fort, archaeologists uncovered an early medieval trading settlement that operated seasonally and was contemporaneous with the later use of Tinnumburg. Finds from this site demonstrate active trade connections, with items such as whetstones from Norway, loom weights, distinctive fibula brooches linked to the Borre style, decorative rock crystal and glass jewelry, loads of amber, and glass cup fragments. Evidence of local glass bead manufacturing further highlights the area’s role in craft and commerce. Similar artifact assemblages were discovered at the Lembecksburg site on the nearby island of Föhr, underscoring broader cultural and economic networks in the North Frisian Islands during this period.

Remains

The Tinnumburg presents as a large circular earthwork with an outer diameter measuring roughly 120 meters and encircling a circumference of about 440 meters. Inside this rampart, the enclosed space spans approximately 80 by 60 meters. The rampart itself rises to nearly seven meters high, standing about two meters above the surrounding sea level, reflecting a significant effort in construction and earth-moving by its builders.

This fortification was originally accessed through at least two main gates positioned on the eastern and southern sides, with a possible third gate facing west. The western entrance led down to a small plateau adjacent to the nearby Döplem lake, indicating a designed connection to the local landscape and waterways. The fort’s northwest boundary is shaped by a tidal creek flowing out to the Wadden Sea, while the southeast side opens onto flat marshland, highlighting a strategic position between sea and land. Before the marshes were diked in the early twentieth century, the Tinnumburg appeared as an island during storm floods, emphasizing its natural defensive advantages.

Within the rampart, archaeologists uncovered remains of sod-walled houses that date from the eighth to tenth centuries. These buildings were constructed from blocks of turf, a practical material well-suited to the marshy environment. Excavations revealed a cultural layer inside the fort about 1.8 meters thick, containing fragments of iron, worked wood, and pottery shards that relate to the late Viking Age phase of occupation. These finds demonstrate both continued habitation and craftsmanship during this period.

Excavations conducted in 1870, 1948, and 1976 confirmed the original construction period around the early Roman era, as well as the later medieval reuse. The archaeological work also uncovered cultural artifacts linking the fort to a network of nearby trading sites, attesting to its significance well beyond simple fortification. Today, the remnants of the Tinnumburg stand as a striking earthwork, preserving traces of multiple centuries of human activity shaped by both local traditions and wider Northern European contacts.