Area Archeologica di Solunto: An Ancient Phoenician, Hellenistic, and Roman Site in Sicily

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: pti.regione.sicilia.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Greek, Phoenician, Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Religious, Sanitation

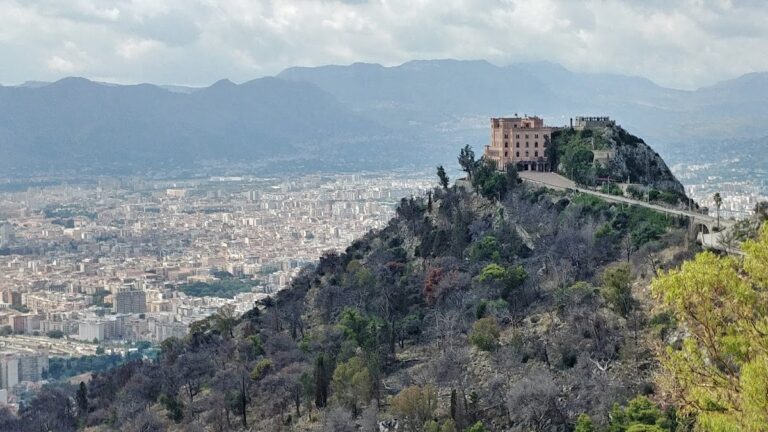

Context

The Area Archeologica di Solunto is located near Santa Flavia in the province of Palermo, on the northern coast of Sicily, Italy. Positioned atop a coastal hill overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea, the site commands a strategic vantage point above the surrounding plains and maritime routes. This elevated terrain provided natural defensive advantages and facilitated control over coastal navigation along Sicily’s northern shoreline. The surrounding Mediterranean environment, characterized by a temperate climate and fertile lands, supported sustained human habitation and agricultural activities.

Archaeological investigations have revealed that Solunto’s occupation spans from its initial settlement by Phoenician colonists in the 8th century BCE through significant Hellenistic urban redevelopment in the 4th century BCE, and later integration into the Roman provincial system by the 3rd century BCE. The site’s gradual abandonment during the late Roman period reflects broader regional socio-political and economic transformations. Its hillside location has contributed to the preservation of urban structures, enabling detailed study of Phoenician, Hellenistic, and Roman urbanism in Sicily.

Excavations initiated in the 19th and 20th centuries have uncovered residential quarters, public buildings, and religious complexes, providing insight into the city’s evolving cultural and political affiliations. Ongoing conservation efforts by Italian heritage authorities aim to safeguard the site’s archaeological fabric and enhance understanding of its role within the Mediterranean historical landscape.

History

Solunto’s archaeological record embodies the complex interplay of indigenous, Phoenician, Greek, and Roman influences that shaped northern Sicily over nearly a millennium. Initially established as a Phoenician settlement in the 8th century BCE, the site later underwent substantial Hellenistic transformation before incorporation into the Roman provincial framework. Its coastal position linked it to maritime trade networks and regional power dynamics, although it remained a secondary center compared to larger Sicilian cities. The site’s decline in late antiquity corresponds with widespread urban contraction in Sicily, though specific details of its abandonment remain elusive.

Sicani and Pre-Hellenistic Period

Recent archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest occupation of the Solunto area may have been established by the Sicani, an indigenous Sicilian population predating Phoenician colonization. The settlement’s location on the slopes of Monte Catalfano aligns with known Sicani settlement patterns favoring defensible rocky promontories. The toponym “Solunto” likely derives from Semitic or archaic Greek terms related to “rock” or “rocky place,” reflecting the site’s prominent topography. This indigenous foundation provides a contextual backdrop for the subsequent Phoenician presence.

Phoenician Period (8th–4th century BCE)

During the 8th century BCE, Solunto was established as a Phoenician coastal settlement, part of a network that included Panormus (modern Palermo) and Motya, as recorded by Thucydides. The site’s elevated position afforded strategic oversight of maritime routes and facilitated participation in Mediterranean trade. Archaeological remains from this period are limited due to modern disturbances but include a necropolis with chamber tombs, an industrial quarter with ceramic kilns, and a probable tofet containing cremated remains and votive stelae. Additional funerary features include an underground tomb with a dromos near Olivella.

Ceramic assemblages comprise imported Ionian kylikes, Corinthian aryballoi, Etruscan bucchero kantharoi, and Phoenician amphorae of Ramón types, indicating active trade connections. The city’s territory experienced raids during Carthaginian conflicts, and in 396 BCE, Dionysius I of Syracuse conquered Solunto amid his campaigns against Carthage, alongside Cefalù and Enna. This conquest likely inflicted significant damage, as Solunto disappears from historical records after 368 BCE, suggesting a period of decline or abandonment.

Hellenistic Period (4th–3rd century BCE)

Following its apparent destruction, Solunto was comprehensively rebuilt on Monte Catalfano in the mid-4th century BCE according to a Hippodamian grid plan, reflecting Greek urban design principles. In 307 BCE, Greek mercenaries abandoned by Agathocles in Africa settled at Solunto, establishing a pronounced Hellenic presence. Epigraphic evidence documents civic institutions such as the amphipoli of Zeus Olympios and hieròthytai, modeled on Syracuse’s political and religious offices, indicating the city’s integration into Hellenistic cultural and administrative frameworks.

The urban fabric features a regular street grid oriented northeast-southwest, intersected by perpendicular stairways adapting to the hillside slope. Residential blocks measure approximately 40 by 80 meters, subdivided by narrow drainage channels. The principal thoroughfare, the Via dell’Agorà, is paved with limestone slabs and later brick tiles, leading to the public sector. Residential architecture reveals social stratification: peripheral houses are modest with simple courtyards, while central dwellings possess peristyles and elaborate mosaic and fresco decoration.

Public monuments include a sanctuary complex retaining Phoenician religious elements such as betyls and altars, a stoa with nine exedrae and seating benches, a large cistern supported by three rows of pillars, a theater accommodating approximately 1,200 spectators, and a bouleuterion with seating for about 100, corresponding to a local senate. The so-called “Ginnasio” is a luxurious residence with a two-story peristyle and mosaic floors; an inscription here references an ephebia and a gymnasiarch named Apollonios, indicating formal youth education. The “Casa di Leda” is a multi-level house featuring shops, a cistern, a peristyle with Doric and Ionic columns, and a rare astrolabe mosaic depicting terrestrial and celestial spheres, likely imported from Alexandria and dated to the mid-2nd century BCE. Other houses along the Via Ippodamo di Mileto display second style frescoes and polychrome tesserae floors, underscoring the city’s Hellenistic cultural milieu.

Roman Period (3rd century BCE–Late Antiquity)

In 254 BCE, during the First Punic War, Solunto came under Roman control as part of the province of Sicilia. Cicero references Solunto among the civitates decumanae, communities subject to Roman taxation, though its precise administrative status remains uncertain. Archaeological evidence indicates a decline in urban vitality by the 1st century CE, with public buildings such as the theater and bouleuterion partially repurposed or abandoned. A large private residence was constructed over part of the theater cavea, signaling the contraction of civic functions.

Domestic decoration from this period includes mosaic floors with white tesserae and black borders, third style frescoes featuring vertical thyrsi supporting garlands dated to the Augustan era, and fourth style frescoes replacing earlier wall paintings. The sanctuary complex continued in use with modifications into the Imperial period. The latest Latin inscription is a dedication by the res publica Soluntinorum to Fulvia Plautilla, wife of Emperor Caracalla, dating to the early 3rd century CE. The city was likely abandoned shortly thereafter, reflecting broader patterns of urban decline in Sicily during late antiquity.

Late Antiquity and Early Medieval Period

Following the collapse of Roman authority, Sicily experienced successive invasions and administrative changes under Vandal and Byzantine rule. Solunto lacks archaeological or textual evidence of significant occupation during this era. The absence of fortifications, ecclesiastical buildings, or inscriptions suggests the site lost its civic and religious functions. Unlike other Sicilian centers, Solunto is not recorded as a bishopric, indicating diminished regional importance.

Regional instability, shifting trade routes, and economic contraction contributed to depopulation. While rural habitation may have persisted in the surrounding countryside, urban life at Solunto ceased. The site’s abandonment exemplifies the decline of smaller coastal settlements in Sicily during early medieval transformations, as fortified towns and rural estates became dominant.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Phoenician Period (8th–4th century BCE)

During the Phoenician occupation, Solunto was inhabited by a community likely comprising Phoenician settlers and indigenous Sicani, forming a multicultural society. Archaeological evidence, including chamber tombs and a probable tofet, indicates ritual practices involving cremation and votive offerings consistent with Phoenician religious customs. The presence of an industrial quarter with kilns suggests local production of ceramics and possibly textiles, supporting artisanal crafts alongside maritime trade.

Imported ceramics such as Ionian kylikes and Corinthian aryballoi demonstrate active participation in Mediterranean exchange networks. The settlement’s elevated position facilitated control over sea routes, enhancing its commercial and defensive roles. Dietary staples likely included cereals, olives, fish, and wine, reflecting regional agricultural and maritime resources. Although direct evidence of clothing is lacking, Phoenician styles such as tunics and cloaks were probably worn. Domestic architecture remains poorly preserved due to modern disturbances, but funerary and industrial remains attest to an organized community life.

Hellenistic Period (4th–3rd century BCE)

Following its reconstruction, Solunto developed as a Hellenized polis with a Hippodamian urban plan and Greek civic institutions. The settlement’s population included Greek mercenaries and local inhabitants adopting Hellenistic cultural practices. Residential architecture reveals social stratification, with wealthier families occupying central houses featuring peristyles, elaborate mosaics, and frescoes, while peripheral dwellings were more modest.

Economic activities encompassed agriculture, artisanal crafts, and commerce, supported by shops with mezzanine dormitories and an industrial quarter. Dietary habits remained Mediterranean, with bread, olives, wine, and fish as staples. Clothing likely followed Greek fashions such as chitons and himations. Religious life combined retained Phoenician elements, evidenced by sanctuaries with betyls and animal sacrifice, alongside Greek cults. Public buildings like the theater and bouleuterion facilitated civic gatherings and political assemblies. An ephebia, attested by inscriptions, provided formal youth education in physical and cultural disciplines, underscoring the city’s institutional complexity.

Roman Period (3rd century BCE–Late Antiquity)

Under Roman rule, Solunto’s population included Roman citizens and local residents, though the city’s civic prominence declined. The site was part of the civitates decumanae, subject to taxation but lacking clear municipium status. Elite families continued to inhabit large houses, while public institutions such as the bouleuterion were repurposed or fell into disuse. Economic life focused on local agriculture, including grain, olives, and vineyards, supported by the fertile hinterland.

The partial conversion of public buildings into private residences and the decline of communal spaces indicate reduced urban activity. Domestic decoration from the Augustan and later periods reflects continued investment in private luxury despite overall contraction. Dietary and clothing practices conformed to Roman provincial norms. Religious practices persisted in modified forms, with the sanctuary complex remaining active, though no Christian presence is documented. Educational and cultural activities diminished alongside the decline of civic institutions.

Late Antiquity and Early Medieval Period

By late antiquity, Solunto was largely abandoned or reduced to a marginal settlement. No archaeological or textual evidence indicates significant occupation during Vandal or Byzantine control. The absence of fortifications, ecclesiastical structures, or inscriptions suggests the community lost its civic and religious functions. Regional instability and economic shifts contributed to depopulation, with urban life ceasing and rural habitation possibly persisting in the surrounding area. The site’s abandonment reflects broader patterns of urban decline in Sicily during early medieval transformations.

Remains

Architectural Features

Solunto’s archaeological remains span from the Phoenician through Roman periods, illustrating a layered urban development on a terraced coastal hill. The city’s construction primarily employs local limestone ashlar masonry, with later Roman structures incorporating mortar and opus caementicium (Roman concrete). The urban plan adapts a roughly orthogonal grid to the hillside topography, with retaining walls supporting terraces and stairways facilitating access. Streets and drainage channels are evident, reflecting organized urban infrastructure.

Defensive architecture is minimal, consistent with the site’s natural elevation providing protection. The preservation state is fragmentary but sufficient to identify functional zones, including residential, public, and industrial areas. Foundations, partial walls, and paved surfaces survive, with some buildings preserved to several courses in height.

Key Buildings and Structures

Residential Quarter

The residential district, primarily dating from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE, comprises multiple houses aligned along narrow streets. Constructed of limestone ashlar, these dwellings feature rectangular rooms arranged around small courtyards. Some houses include hypocaust heating systems, identified by pilae stacks supporting raised floors, dating to the 1st century CE. Floors are often paved with opus signinum, a waterproof mortar. Wall remnants show traces of plaster, though frescoes have not survived. Door and window openings indicate multi-room layouts. The residential area contracts during late antiquity, with some buildings partially abandoned or repurposed.

Public Baths

The bath complex, constructed in the late 1st century BCE near the city center, consists of a sequence of rooms including a caldarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm room), and frigidarium (cold bath). The caldarium retains remains of a hypocaust system with pilae stacks and channels for hot air circulation beneath the floor. Walls are built in opus reticulatum, a Roman masonry technique using diamond-shaped tufa blocks. The frigidarium contains a basin lined with waterproof mortar. Minor repairs occurred in the 2nd century CE, but no evidence of later reuse exists. Partial walls and floor levels remain visible.

Forum Area

The forum precinct, dating to the 2nd century BCE, occupies a terraced plateau near the city’s summit. It includes a paved open space surrounded by porticoes supported by limestone columns, some preserved in situ or as fallen fragments. The paving consists of large polygonal limestone slabs. Adjacent foundations belong to a basilica-like building with a rectangular plan and internal divisions, possibly serving administrative functions. Walls are constructed of ashlar masonry with mortar. No decorative elements such as mosaics or inscriptions have been found. The forum area is partially excavated, with some structures visible only as foundation outlines.

Theatre

The theater, built in the 2nd century BCE on the southern slope, features a cavea (seating area) hewn into the rock with surviving stone benches arranged semicircularly. The orchestra is paved with limestone slabs. Foundations of the scaenae frons (stage building) remain, constructed in ashlar masonry with rectangular blocks. Entrance passages (vomitoria) are partially preserved. No decorative architectural elements or stage machinery have been documented. The theater was abandoned by the 3rd century CE without evidence of later modifications.

Necropolis

The necropolis lies on the eastern slope outside the main settlement, with tombs dating from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE, primarily of Phoenician origin. Funerary structures include rock-cut chamber tombs and arcosolia (arched recesses) carved into limestone. Some tombs contain stone sarcophagi and funerary stelae with incised geometric motifs. Grave goods include pottery and small metal objects. The necropolis is partially excavated, with many tombs accessible, though some remain unexcavated or collapsed.

Other Remains

A network of cisterns and water channels constructed in the 3rd century BCE is present, lined with waterproof opus signinum mortar for rainwater collection and storage. Several workshops and storage rooms, identified by their layout and associated finds such as hearths and work surfaces, are dispersed throughout the settlement. These buildings have simple rectangular plans with stone foundations. Paved streets with curbstones and drainage channels are visible in multiple sectors, illustrating the city’s infrastructure. No substantial military fortifications or temples have been conclusively identified.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded a diverse ceramic assemblage spanning Phoenician, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. Phoenician ceramics include handmade red-slip ware and amphorae typical of the 8th to 5th centuries BCE. Hellenistic layers contain wheel-made painted tableware, while Roman deposits include fine terra sigillata and coarse wares. Amphora fragments indicate imports from North Africa and Campania, evidencing trade connections.

Inscriptions are scarce but include Latin dedicatory texts from the 1st century BCE to 2nd century CE, primarily near the forum and baths, recording building dedications and local magistrates. Coins recovered range from the late Republican period through the 3rd century CE, featuring emperors such as Augustus, Trajan, and Severus Alexander. These were mainly found in domestic contexts and street layers.

Tools include iron agricultural implements and bronze craft tools from workshop areas. Domestic artifacts such as oil lamps, cooking vessels, and glass fragments have been recovered from residential quarters. Religious artifacts are limited to small terracotta figurines and altar fragments, mainly from Hellenistic contexts, with no large temple remains documented.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Solunto are generally preserved at the foundation and lower wall levels, with some structures standing several meters high. The theater’s stone seating and the hypocaust remains of the bath complex are among the best-preserved features. Restoration efforts have stabilized walls and paved areas using original materials supplemented by modern mortar for consolidation. Some reconstructed elements, such as column bases in the forum, are modern replacements intended to support fragile remains.

Vegetation growth and erosion present ongoing conservation challenges, particularly on exposed terraces and necropolis slopes. The site is protected under Italian heritage legislation, with active management by local authorities. Excavations continue selectively, focusing on areas at risk of degradation. Some sectors remain stabilized but unexcavated to preserve stratigraphy. Looting has been minimal due to the site’s relative isolation and protective measures.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of Solunto remain unexcavated, including the northern residential district and parts of the eastern slope near the necropolis. Surface surveys and geophysical studies have identified subsurface anomalies consistent with buried walls and street layouts. The western sector adjacent to the forum shows potential for further excavation but is currently restricted to preserve site integrity. Modern agricultural activity limits access in some peripheral zones.

Future excavation plans prioritize conservation and non-invasive methods, balancing research objectives with preservation. The site’s hillside topography and vegetation cover also constrain extensive archaeological interventions.